By Ed Yong

When an animal’s body consists almost entirely of leg, its biology gets really weird.

If sea spiders had a creation myth, it would go something like this. An inebriated deity stumbles home after a hard day’s creating, finds a bunch of leftover legs, glues them together, and zaps them to life before passing out and forgetting to add anything else. The resulting creature—all leg and little else—scuttles away to conquer the oceans.

This is fiction, of course, but it’s only slightly more fanciful than the actual biology of sea spiders. These bizarre marine creatures have four to six pairs of spindly, jointed legs that convene at a torso that barely exists. “They have to do most of their business in their legs,” says Amy Moran from the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, who studies these animals. They have, for example, no lungs, gills, or respiratory organs of any kind. Instead, they rely on oxygen diffusing passively across the large surface area provided by their legs.

Their genitals are found on their legs, too. A female will grow eggs in her thighs—“it’s as if my arms were full of ping-pong balls,” says Moran—and release them through pores. A male, clambering over her, releases sperm from similar pores to fertilize the eggs, which he scoops up and carries around. Among these animals, the dads care for the young.

The legs are also where most of sea spiders’ digestion takes place. There’s so little distance between their mouths and anuses that their guts send long branches down each leg. Put your wrists together, spread your hands out, and splay your fingers—that’s the shape of a sea spider’s gut.

For all their prominence, the legs themselves are oddly clumsy. “[Sea spiders are] very slow, they stumble around, and they fall over a lot,” says Moran. “Frankly, I don’t know how they get away with being so ineffective.” Perhaps it has to do with their choice of food. They feed on immobile prey like sea anemones or sponges, whose juices they suck with stabbing mouthparts at the end of their tiny heads.

Sea spiders, also known as pycnogonids, aren’t actual spiders. There’s a hazy consensus that they belong with the chelicerates—the group that does include true spiders—although some geneticists think that they’re more distantly related. Regardless, “they’re about as closely related to a terrestrial spider as a seahorse is to a horse,” says Moran.

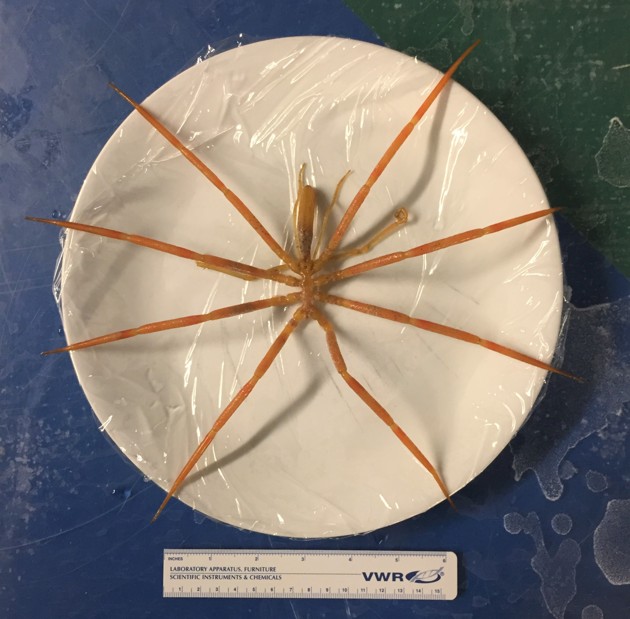

They do live in the sea, though, so the Department of Naming Things got things half-right at least. There are around 1,300 known species, found in oceans all over the world. The smallest are just a millimeter long. The biggest, found in Antarctica, are the size of dinner plates. To prove this, here is a picture of one sitting on a dinner plate.

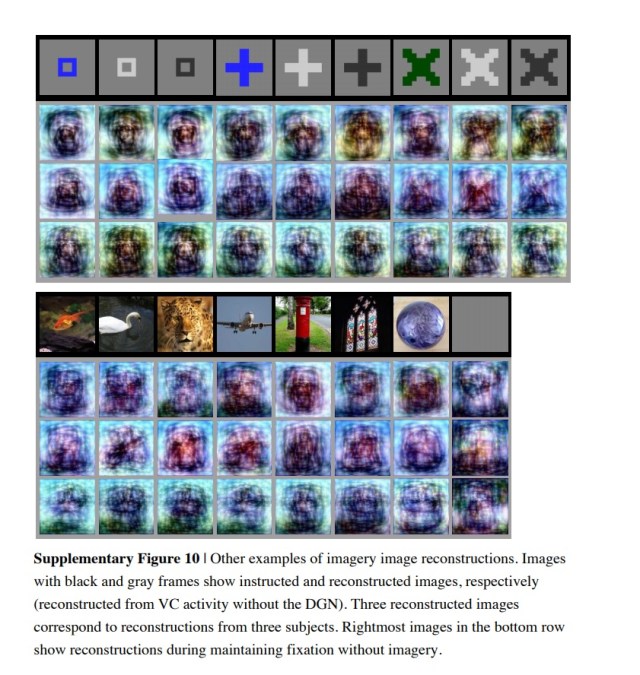

Moran and her colleague Arthur Woods started studying these creatures because they wanted to know why the giant Antarctic species got so big. Bigger animals need more oxygen. They need to get more of the gas into their bloodstreams, and they need to pump that blood around their bodies. Humans do so with our hearts, but when Woods examined the hearts of sea spiders, he discovered yet another remarkable trait about these already remarkable animals.

He injected fluorescent chemicals into their blood to see how far their hearts can push blood into their legs. Not very far, it turns out. Instead, the creatures largely pump their blood using their guts.

Each leg is a solid tube containing a branch of the sea spider’s guts and some blood vessels. The guts can contract to move food along, just as ours can. But unlike our abdomens, which are flexible, a sea spider’s leg is hard and can’t stretch or expand. If it pushes digestive fluids down its legs, it also forces blood back in the other direction. If it pushes the digestive fluids up, the blood goes back down.

After oxygen passively diffuses into the animal’s legs, it is actively pushed into its torso by the contracting guts.

Woods confirmed this by capturing sea spiders and lowering the oxygen levels in their water. In response, the animals’ guts started contracting faster. “It’s like when you take a person up to altitude and they breathe faster and their heart rate goes up,” says Moran. Same thing, except the sea spiders “are using their legs as gills and their guts as hearts.”

The creature’s actual heart is too small and weak to push blood down the long legs. It only takes over once the blood has reached the animal’s core, circulating it around the torso and head. Finally, says Claudia Arango, a sea spider specialist who was involved in the new study, “we know how they live without having an specialized system for pumping blood.”

Nothing else in nature behaves quite like this. Sea cucumbers breathe using feathery outgrowths of their guts, and several insect larvae breathe using butt snorkels. But all of these species have changed a part of their gut to take in oxygen. The sea spiders are the only ones that use the guts to pump their blood.

Like everything else about sea spiders, the origin of this weird circulatory system is mysterious. These animals are an ancient group that first appeared during around 500 million years ago during the Cambrian period—the point in Earth’s history when most modern animal groups exploded into existence. It could be that the earliest members already had spindly legs and branching guts, and simply co-opted these into ersatz hearts. Alternatively, the double-purpose guts may have come first, allowing the sea spiders to evolve their long legs.

Whatever the route, given how widespread and persistent these animals are, the results were undeniably successful.