A battered diamond that survived a trip from “hell” confirms a long-held theory: Earth’s mantle holds an ocean’s worth of water.

“It’s actually the confirmation that there is a very, very large amount of water that’s trapped in a really distinct layer in the deep Earth,” said Graham Pearson, lead study author and a geochemist at the University of Alberta in Canada. The findings were recently published in the journal Nature.

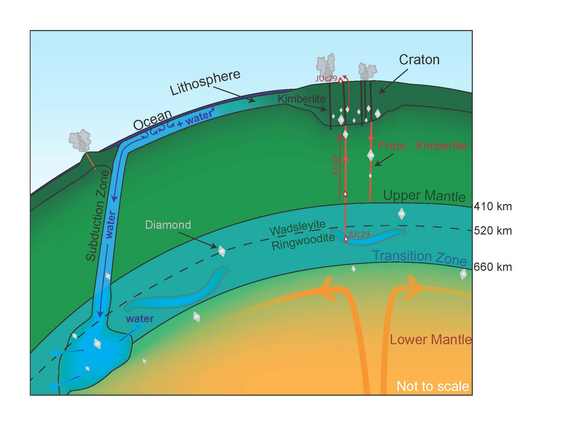

The worthless-looking diamond encloses a tiny piece of an olivine mineral called ringwoodite, and it’s the first time the mineral has been found on Earth’s surface in anything other than meteorites or laboratories. Ringwoodite only forms under extreme pressure, such as the crushing load about 320 miles (515 kilometers) deep in the mantle.

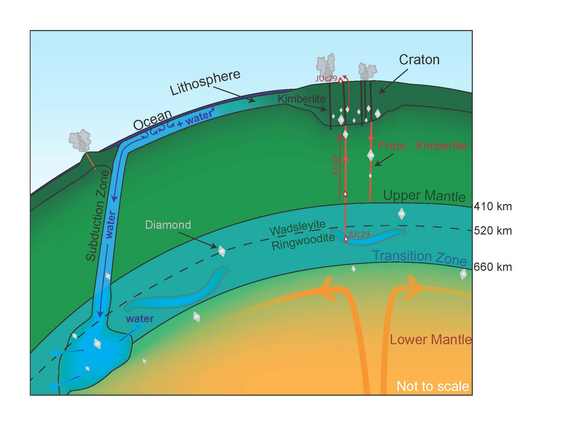

Most of Earth’s volume is mantle, the hot rock layer between the crust and the core. Too deep to drill, the mantle’s composition is a mystery leavened by two clues: meteorites, and hunks of rock heaved up by volcanoes. First, scientists think the composition of the Earth’s mantle is similar to that of meteorites called chondrites, which are chiefly made of olivine. Second, lava belched by volcanoes sometimes taps the mantle, bringing up chunks of odd minerals that hint at the intense heat and pressure olivine endures in the bowels of the Earth.

In recent decades, researchers have also recreated mantle settings in laboratories, zapping olivine with lasers, shooting minerals with massive guns and squeezing rocks between diamond anvils to mimic the Earth’s interior.

These laboratory studies suggest that olivine morphs into a variety of forms corresponding to the depth at which it is found. The new forms of crystal accommodate the increasing pressures. Changes in the speed of earthquake waves also support this model. Seismic waves suddenly speed up or slow down at certain depths in the mantle. Researcher think these speed zones arise from olivine’s changing configurations. For example, 323 to 410 miles (520 to 660 km) deep, between two sharp speed breaks, olivine is thought to become ringwoodite. But until now, no one had direct evidence that olivine was actually ringwoodite at this depth.

“Most people (including me) never expected to see such a sample. Samples from the transition zone and lower mantle are exceedingly rare and are only found in a few, unusual diamonds,” Hans Keppler, a geochemist at the University of Bayreuth in Germany, wrote in a commentary also published in Nature.

The diamond from Brazil confirms that the models are correct: Olivine is ringwoodite at this depth, a layer called the mantle transition zone. And it resolves a long-running debate about water in the mantle transition zone. The ringwoodite is 1.5 percent water, present not as a liquid but as hydroxide ions (oxygen and hydrogen atoms bound together). The results suggest there could be a vast store of water in the mantle transition zone, which stretches from 254 to 410 miles (410 to 660 km) deep.

“It translates into a very, very large mass of water, approaching the sort of mass of water that’s present in all the world’s ocean,” Pearson told Live Science’s Our Amazing Planet.

Plate tectonics recycles Earth’s crust by pushing and pulling slabs of oceanic crust into subduction zones, where it sinks into the mantle. This crust, soaked by the ocean, ferries water into the mantle. Many of these slabs end up stuck in the mantle transition zone. “We think that a significant portion of the water in the mantle transition zone is from the emplacement of these slabs,” Pearson said. “The transition zone seems to be a graveyard of subducted slabs.”

Keppler noted that it’s possible the volcanic eruption that brought the deep diamond to Earth’s surface may have sampled an unusually water-rich part of the mantle, and that not all of the transition-zone layer may be as wet as indicated by the ringwoodite.

“If the source of the magma is an unusual mantle reservoir, there is the possibility that, at other places in the transition zone, ringwoodite contains less water than the sample found by Pearson and colleagues,” Keppler wrote. “However, in light of this sample, models with anhydrous, or water-poor, transition zones seem rather unlikely.”

A violent volcanic eruption called a kimberlite quickly carried this particular diamond from deep in the mantle. “The eruption of a kimberlite is analogous to dropping a Mentos mint into a bottle of soda,” Pearson said. “It’s a very energetic, gas-charged reaction that blasts its way to Earth’s surface.”

The tiny, green crystal, scarred from its 325-mile (525 km) trip to the surface, was bought from diamond miners in Juína, Brazil. The mine’s ultradeep diamonds are misshapen and beaten up by their long journey. “They literally look like they’ve been to hell and back,” Pearson said. The diamonds are usually discarded because they carry no commercial value, he said, but for geoscientists, the gems provide a rare peek into Earth’s innards.

The ringwoodite discovery was accidental, as Pearson and his co-authors were actually searching for a means of dating the diamonds. The researchers think careful sample preparation is the key to finding more ringwoodite, because heating ultradeep diamonds, as happens when scientists polish crystals for analysis, causes the olivine to change shape.

“We think it’s possible ringwoodite may have been found by other researchers before, but the way they prepared their samples caused it to change back to a lower-pressure form,” Pearson said.

http://www.livescience.com/44057-diamond-inclusions-mantle-water-earth.html