Despite a known link between a masculine-looking face and aggression in men, macho-faced soldiers didn’t survive Finland’s World War II Winter War in greater numbers than recruits with less masculine faces.

The macho-looking men did, however, have more children in their lifetimes than thinner-faced guys, suggesting that face shape is a sign of evolutionary fitness.

The new findings, published today May 7 in the journal Biology Letters, reveal nuances in how hormones, genetics and societal structures might work together to influence evolution. For example, the technology of 20th-century warfare may have turned survival into a matter of luck rather than evolutionary fitness, said study leader John Loehr, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Helsinki Lammi Biological Station.

“You have very little individual ability to change your fate,” Loehr told LiveScience. “You’re put in a situation where you and the 20 other people who are in your trench are hit by a shell, and it’s game over.”

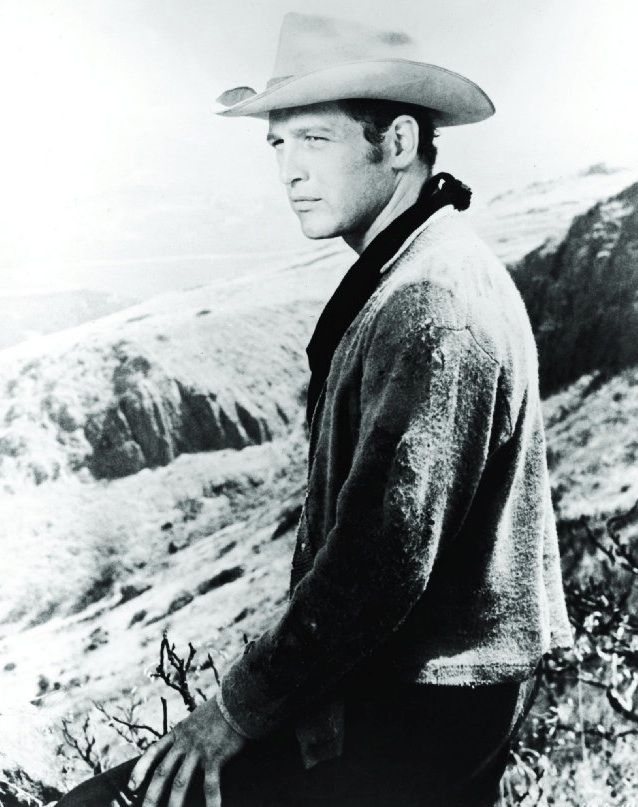

High levels of testosterone during development are linked with a certain macho look: a broad face, strong jaw and narrow eyes. Any number of swaggering movie stars, from Paul Newman to Channing Tatum (“G.I. Joe”), has parlayed this face shape into successful onscreen careers.

Meanwhile, psychologists have found that guys with Newman’s squint or Tatum’s wide cheekbones tend to be higher in aggression than men with thinner faces. One study on Japanese baseball players, released in April, found that wider-faced players hit more home runs. And in 2008, Canadian researchers discovered that hockey players with wider faces spent more time in the penalty box than other players for aggressive behavior.

The hockey player finding got Loehr thinking about whether high testosterone (and thus, aggression) might confer a survival advantage on wider-faced guys.

“The obvious thing, for me, was, ‘Well, can we get some military data?'” he said.

Fortunately, he could. Finland is a country with meticulous record-keeping, and at the library for the Finnish National Defense in Helsinki, Loehr inquired of a librarian where he might find resources with photos of World War II soldiers (for facial width measurements) as well as personal data about those men.

“She sort of walked around the corner and there were rows of these books sitting there with all the pictures and an amazing amount of personal data,” Loehr said.

Over several months, Loehr pulled together other resources, including photo books of dead soldiers compiled during Finland’s three-and-a-half-month Winter War with the Soviet Union in 1939. Using these old books, he was able to measure facial widths of both surviving soldiers and men lost during the war. He also knew these men’s ranks and how many children they had during their lifetimes.

Military service was and still is mandatory in Finland, Loehr said, so World War II soldiers were a good representation of the male population.

Loehr focused on three WWII regiments, for a total of 795 soldiers. He and co-researcher Robert O’Hara of the Biodiversity and Climate Research Center in Germany found that wider-faced soldiers fathered more children than narrower-faced ones. The finding would have been expected by evolutionary researchers, given previous studies suggesting that fertile women are drawn to more masculine men.

The other findings were more surprising. For one, the wider-faced guys were actually less likely than narrow-faced men to rank higher in the military hierarchy. In other words, the higher the rank, the more likely the man was to have a narrow face.

“That’s a curious one,” Loehr said. Ecologically, he said, you’d expect the men who fathered more children in a community to be the socially dominant guys.

“For human species, it’s perhaps more nuanced,” Loehr said. For example, wide-faced guys have been shown in laboratory experiments to be less trustworthy. Trustworthiness might be more important for military leaders than dominance or aggression.

Another possibility is that the wider-faced guys could have moved up the military ranks during periods of conflict, Loehr said, as his findings were based on rank before the Winter War started. A study published in June 2012 found that in competitive situations, macho-faced guys are the most likely to work together to defeat a common enemy. If that’s the case, any testosterone advantage may not have come out until war began.

Second, Loehr and O’Hara found that face shape didn’t affect survival at all. A wider-faced man was equally as likely to die in battle as a man with a narrower face.

Technology may trump testosterone, Loehr said. One study, published in 2012 in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior, found that in fights involving hand-to-hand combat or other physical contact, narrow-faced men were more likely to die than wide-faced men. In conflicts where a gun, poison or other remote weapon was used, face shape made no difference.

The same could be true for Finnish soldiers, who fought and died with guns in the trenches, Loehr said.

“You would think that thousands of years ago, when combat would have been more hand-to-hand, without much use of tools, that you would have a different result,” he said. “It’s possible that humans have changed how selection can operate by developing this technology.”

http://www.livescience.com/29393-macho-faces-war-survival.html