By Zaria Gorvett

It’s on your passport. It’s how criminals are identified in a line-up. It’s how you’re recognised by old friends on the street, even after years apart. Your face: it’s so tangled up with your identity, soon it may be all you need to unlock your smartphone, access your office or buy a house.

Underpinning it all is the assurance that your looks are unique. And then, one day your illusions are smashed.

“I was the last one on the plane and there was someone in my seat, so I asked the guy to move. He turned around and he had my face,” says Neil Douglas, who was on his way to a wedding in Ireland when it happened.

“The whole plane looked at us and laughed. And that’s when I took the selfie.” The uncanny events continued when Douglas arrived at his hotel, only to find the same double at the check-in desk. Later their paths crossed again at a bar and they accepted that the universe wanted them to have a drink. He woke up the next morning with a hangover and an Argentinian radio show on the phone – the picture had gone viral.

Folk wisdom has it that everyone has a doppelganger; somewhere out there there’s a perfect duplicate of you, with your mother’s eyes, your father’s nose and that annoying mole you’ve always meant to have removed. The notion has gripped the popular imagination for millennia – it was the subject of one of the oldest known works of literature – inspiring the work of poets and scaring queens to death.

But is there any truth in it? We live on a planet of over seven billion people, so surely someone else is bound to have been born with your face? It’s a silly question with serious implications – and the answer is more complicated than you might think.

In fact until recently no one had ever even tried to find out. Then last year Teghan Lucas set out to test the risk of mistaking an innocent double for a killer.

Armed with a public collection of photographs of U.S. military personnel and the help of colleagues from the University of Adelaide, Teghan painstakingly analysed the faces of nearly four thousand individuals, measuring the distances between key features such as the eyes and ears. Next she calculated the probability that two peoples’ faces would match.

What she found was good news for the criminal justice system, but likely to disappoint anyone pining for their long-lost double: the chances of sharing just eight dimensions with someone else are less than one in a trillion. Even with 7.4 billion people on the planet, that’s only a one in 135 chance that there’s a single pair of doppelgangers. “Before you could always be questioned in a court of law, saying ‘well what if someone else just looks like him?’ Now we can say it’s extremely unlikely,” says Teghan.

The results can be explained by the famed infinite monkey problem: sit a monkey in front of a typewriter for long enough and eventually it will surely write the Complete Works of William Shakespeare by randomly hitting, biting and jumping up and down on the keys on the board.

It’s a mathematical certainty, but reversing the problem reveals just how staggeringly long the monkey would have to toil. Ignoring grammar, the monkey has a one in 26 chance of correctly typing the first letter of Macbeth. So far, so good. But already by the second letter the chance has shrunk to one in 676 (26 x 26) and by the end of the fourth line (22 letters) it’s one in 13 quintillion. When you multiply probabilities together, the chances of something actually happening disappear very, very quickly.

Besides, the wide array in human guises is undoubtedly down to more than eight traits. Far from everyone having a long-lost “twin”, in Teghan’s view it’s more likely no one does.

But that’s not quite the end of the story. The study relied on exact measurements; if your doppelganger’s ears are 59 mm but yours are 60, your likeness wouldn’t count. In any case, you probably won’t remember the last time you clocked an uncanny resemblance based on the length of someone’s ears.

There may be another way – and it all comes down to what you mean by a doppelganger. “It depends whether we mean ‘lookalike to a human’ or ‘lookalike to facial recognition software’,” says David Aldous, a statistician at U.C. Berkeley.

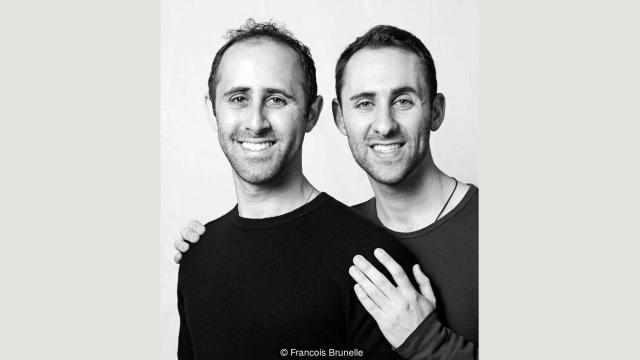

Francois Brunelle, who has photographed over 200 pairs of doubles for his project I’m not a look-alike, agrees. “For me it’s when you see someone and you think it’s the other person. It’s the way of being, the sum of the parts.” When seen apart, his subjects looked like perfect clones. “When you get them together and you see them side by side, sometimes you feel that they are not the same at all.”

If fine details aren’t important, suddenly the possibility of having a lookalike looks a lot more realistic. But is this really true? To find out, first we need to get to grips with what’s going on when we recognise a familiar face.

Take the illusion of Bill Clinton and Al Gore which circulated the internet before their re-election in 1997. It features a seemingly unremarkable picture of the two men standing side by side. On closer inspection, you can see that Gore’s “internal” facial features – his eyes, nose and mouth – have been replaced by Clinton’s. Even without these traits, with his underlying facial structure intact Al Gore looks completely normal.

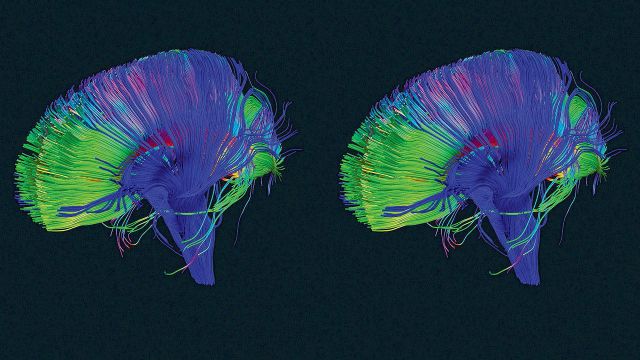

It’s a striking demonstration of the way faces are stored in the brain: more like a map than an image. When you bump into a friend on the street, the brain immediately sets to work recognising their features – such as hairline and skin tone – individually, like recognising Italy by its shape alone. But what if they’ve just had a haircut? Or they’re wearing makeup?

To ensure they can be recognised in any context, the brain employs an area known as the fusiform gyrus to tie all the pieces together. If you compare it to finding a country on a map, this is like checking it has a border with France and a coast. This holistic ‘sum of the parts’ perception is thought to make recognising friends a lot more accurate than it would be if their features were assessed in isolation. Crucially, it also fudges the importance of some of the subtler details.

“Most people concentrate on superficial characteristics such as hair-line, hair style, eyebrows,” says Nick Fieller, a statistician involved in The Computer-Aided Facial Recognition Project. Other research has shown we look to the eyes, mouth and nose, in that order.

Then it’s just a matter of working out the probability that someone else will have all the same versions as you. “There are only so many genes in the world which specify the shape of the face and millions of people, so it’s bound to happen,” says Winrich Freiwald, who studies face perception at Rockefeller University. “For somebody with an ‘average’ face it’s comparatively easy to find good matches,” says Fieller.

Let’s assume our man has short blonde hair, brown eyes, a fleshy nose (like Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh), a round face and a full beard. Research into the prevalence of these features is hard to come by, but he’s off to a promising start: 55% of the global population has brown eyes.

Meanwhile more than one in ten people have round faces, according to research funded by a cosmetics company. Then there’s his nose. A study of photographs taken in Europe and Israel identified the ‘fleshy’ type as the most prevalent (24.2%). In the author’s view these are also the least attractive.

Finally – how much hair is there out there? If you thought this was too frivolous for serious investigation, you’d be wrong: among 24,300 people surveyed at a Florida theme park, 82% of men had hair shorter than shoulder-length. Natural blondes, however, constitute just 2%. As the ‘beard capital’ of the world, in the UK most men have some form of facial hair and nearly one in six have a full beard.

A simple calculation (male x brown eyes x blonde x round face x fleshy nose x short hair x full beard) reveals the probability of a person possessing all these features is just over one in 100,000 (0.00001020%).

That would give our guy no less than 74,000 potential doppelgangers. Of course many of these prevalence rates aren’t global, so this is very imprecise. But judging by the number of celebrity look-alikes out there, it might not be far off. “After the picture went viral I think there was a small army of us at some point,” says Douglas.

So what’s the probability that everyone has a duplicate roaming the earth? The simplest way to guess would be to estimate the number of possible faces and compare it to the number of people alive today.

You might expect that even if there are 7.4 billion different faces out there, with 7.4 billion people on the planet there’s clearly one for everyone. But there’s a catch. You’d actually need close to 150 billion people for that to be statistically likely. The discrepancy is down to a statistical quirk known as the coupon collector’s problem. Let’s say there are 50 coupons in a jar and each time you draw one it’s put back in. How many would you need to draw before it’s likely you’ve chosen each coupon at least once?

It takes very little time to collect the first few coupons. The trouble is finding the last few: on average drawing the last one takes about 50 draws on its own, so to collect all 50 you need about 225. It’s possible that most people have a doppelganger – but everyone? “There’s a big difference between being lucky sometimes and being lucky always,” says Aldous.

No one has any good idea what the first number is. Indeed, it may never be possible to say definitively, since the perception of facial resemblance is subjective. Some people have trouble recognising themselves in photos, while others rarely forget a face. And how we perceive similarity is heavily influenced by familiarity. “Some doubles when they get together, they say ‘No I don’t see it. Really, I don’t.’ It’s so obvious to everyone else; it’s a little crazy to hear that,” says Brunelle.

Even so, Fieller thinks there’s a good chance. “I think most people have somebody who is a facial lookalike unless they have a truly exceptional and unusual face,” he says. Friewald agrees. “I think in the digital age which we are entering, at some point we will know because there will be pictures of almost everyone online,” he says.

Why are we so interested anyway? “If you meet someone that looks like you, you have an instant bond because you share something.” Brunelle has received interest from thousands of people searching for their lookalikes, especially from China – a fact he puts down to the one-child policy. Research has shown we judge similar looking-people to be more trustworthy and attractive – a factor thought to contribute to our voting choices.

It may stem back to our deep evolutionary past, when facial resemblance was a useful indicator of kinship. In today’s globalised world, this is misguided. “It is entirely possible for two people with similar facial features to have DNA that is no more similar than that of two random people,” says Lavinia Paternoster, a geneticist at the University of Bristol.

And before you go fantasising about doing a temporary life-swap with your ‘twin’, there’s no guarantee you’ll have anything in common physically either. “Well I’m 5’7 and he’s 6’3… so it’s mainly in the face,” says Douglas.

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20160712-you-are-surprisingly-likely-to-have-a-living-doppelganger