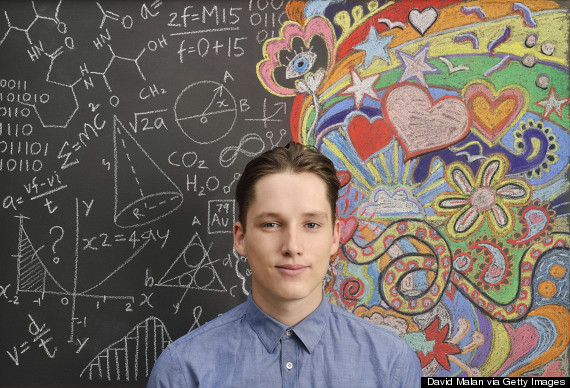

Creativity works in mysterious and often paradoxical ways. Creative thinking is a stable, defining characteristic in some personalities, but it may also change based on situation and context. Inspiration and ideas often arise seemingly out of nowhere and then fail to show up when we most need them, and creative thinking requires complex cognition yet is completely distinct from the thinking process.

Neuroscience paints a complicated picture of creativity. As scientists now understand it, creativity is far more complex than the right-left brain distinction would have us think (the theory being that left brain = rational and analytical, right brain = creative and emotional). In fact, creativity is thought to involve a number of cognitive processes, neural pathways and emotions, and we still don’t have the full picture of how the imaginative mind works.

And psychologically speaking, creative personality types are difficult to pin down, largely because they’re complex, paradoxical and tend to avoid habit or routine. And it’s not just a stereotype of the “tortured artist” — artists really may be more complicated people. Research has suggested that creativity involves the coming together of a multitude of traits, behaviors and social influences in a single person.

“It’s actually hard for creative people to know themselves because the creative self is more complex than the non-creative self,” Scott Barry Kaufman, a psychologist at New York University who has spent years researching creativity, told The Huffington Post. “The things that stand out the most are the paradoxes of the creative self … Imaginative people have messier minds.”

While there’s no “typical” creative type, there are some tell-tale characteristics and behaviors of highly creative people. Here are 18 things they do differently.

They daydream.

Creative types know, despite what their third-grade teachers may have said, that daydreaming is anything but a waste of time.

According to Kaufman and psychologist Rebecca L. McMillan, who co-authored a paper titled “Ode To Positive Constructive Daydreaming,” mind-wandering can aid in the process of “creative incubation.” And of course, many of us know from experience that our best ideas come seemingly out of the blue when our minds are elsewhere.

Although daydreaming may seem mindless, a 2012 study suggested it could actually involve a highly engaged brain state — daydreaming can lead to sudden connections and insights because it’s related to our ability to recall information in the face of distractions. Neuroscientists have also found that daydreaming involves the same brain processes associated with imagination and creativity.

They observe everything.

The world is a creative person’s oyster — they see possibilities everywhere and are constantly taking in information that becomes fodder for creative expression. As Henry James is widely quoted, a writer is someone on whom “nothing is lost.”

The writer Joan Didion kept a notebook with her at all times, and said that she wrote down observations about people and events as, ultimately, a way to better understand the complexities and contradictions of her own mind:

“However dutifully we record what we see around us, the common denominator of all we see is always, transparently, shamelessly, the implacable ‘I,'” Didion wrote in her essay On Keeping A Notebook. “We are talking about something private, about bits of the mind’s string too short to use, an indiscriminate and erratic assemblage with meaning only for its marker.”

They work the hours that work for them.

Many great artists have said that they do their best work either very early in the morning or late at night. Vladimir Nabokov started writing immediately after he woke up at 6 or 7 a.m., and Frank Lloyd Wright made a practice of waking up at 3 or 4 a.m. and working for several hours before heading back to bed. No matter when it is, individuals with high creative output will often figure out what time it is that their minds start firing up, and structure their days accordingly.

They take time for solitude.

In order to be open to creativity, one must have the capacity for constructive use of solitude. One must overcome the fear of being alone,” wrote the American existential psychologist Rollo May.

Artists and creatives are often stereotyped as being loners, and while this may not actually be the case, solitude can be the key to producing their best work. For Kaufman, this links back to daydreaming — we need to give ourselves the time alone to simply allow our minds to wander.

“You need to get in touch with that inner monologue to be able to express it,” he says. “It’s hard to find that inner creative voice if you’re … not getting in touch with yourself and reflecting on yourself.”

They turn life’s obstacles around.

Many of the most iconic stories and songs of all time have been inspired by gut-wrenching pain and heartbreak — and the silver lining of these challenges is that they may have been the catalyst to create great art. An emerging field of psychology called post-traumatic growth is suggesting that many people are able to use their hardships and early-life trauma for substantial creative growth. Specifically, researchers have found that trauma can help people to grow in the areas of interpersonal relationships, spirituality, appreciation of life, personal strength, and — most importantly for creativity — seeing new possibilities in life.

“A lot of people are able to use that as the fuel they need to come up with a different perspective on reality,” says Kaufman. “What’s happened is that their view of the world as a safe place, or as a certain type of place, has been shattered at some point in their life, causing them to go on the periphery and see things in a new, fresh light, and that’s very conducive to creativity.”

They seek out new experiences.

Creative people love to expose themselves to new experiences, sensations and states of mind — and this openness is a significant predictor of creative output.

“Openness to experience is consistently the strongest predictor of creative achievement,” says Kaufman. “This consists of lots of different facets, but they’re all related to each other: Intellectual curiosity, thrill seeking, openness to your emotions, openness to fantasy. The thing that brings them all together is a drive for cognitive and behavioral exploration of the world, your inner world and your outer world.”

They “fail up.”

Resilience is practically a prerequisite for creative success, says Kaufman. Doing creative work is often described as a process of failing repeatedly until you find something that sticks, and creatives — at least the successful ones — learn not to take failure so personally.

“Creatives fail and the really good ones fail often,” Forbes contributor Steven Kotler wrote in a piece on Einstein’s creative genius.

They ask the big questions.

Creative people are insatiably curious — they generally opt to live the examined life, and even as they get older, maintain a sense of curiosity about life. Whether through intense conversation or solitary mind-wandering, creatives look at the world around them and want to know why, and how, it is the way it is.

They people-watch.

Observant by nature and curious about the lives of others, creative types often love to people-watch — and they may generate some of their best ideas from it.

“[Marcel] Proust spent almost his whole life people-watching, and he wrote down his observations, and it eventually came out in his books,” says Kaufman. “For a lot of writers, people-watching is very important … They’re keen observers of human nature.”

They take risks.

Part of doing creative work is taking risks, and many creative types thrive off of taking risks in various aspects of their lives.

“There is a deep and meaningful connection between risk taking and creativity and it’s one that’s often overlooked,” contributor Steven Kotler wrote in Forbes. “Creativity is the act of making something from nothing. It requires making public those bets first placed by imagination. This is not a job for the timid. Time wasted, reputation tarnished, money not well spent — these are all by-products of creativity gone awry.”

They view all of life as an opportunity for self-expression.

Nietzsche believed that one’s life and the world should be viewed as a work of art. Creative types may be more likely to see the world this way, and to constantly seek opportunities for self-expression in everyday life.

“Creative expression is self-expression,” says Kaufman. “Creativity is nothing more than an individual expression of your needs, desires and uniqueness.”

They follow their true passions.

Creative people tend to be intrinsically motivated — meaning that they’re motivated to act from some internal desire, rather than a desire for external reward or recognition. Psychologists have shown that creative people are energized by challenging activities, a sign of intrinsic motivation, and the research suggests that simply thinking of intrinsic reasons to perform an activity may be enough to boost creativity.

“Eminent creators choose and become passionately involved in challenging, risky problems that provide a powerful sense of power from the ability to use their talents,” write M.A. Collins and T.M. Amabile in The Handbook of Creativity.

They get out of their own heads.

Kaufman argues that another purpose of daydreaming is to help us to get out of our own limited perspective and explore other ways of thinking, which can be an important asset to creative work.

“Daydreaming has evolved to allow us to let go of the present,” says Kaufman. “The same brain network associated with daydreaming is the brain network associated with theory of mind — I like calling it the ‘imagination brain network’ — it allows you to imagine your future self, but it also allows you to imagine what someone else is thinking.”

Research has also suggested that inducing “psychological distance” — that is, taking another person’s perspective or thinking about a question as if it was unreal or unfamiliar — can boost creative thinking.

They lose track of the time.

Creative types may find that when they’re writing, dancing, painting or expressing themselves in another way, they get “in the zone,” or what’s known as a flow state, which can help them to create at their highest level. Flow is a mental state when an individual transcends conscious thought to reach a heightened state of effortless concentration and calmness. When someone is in this state, they’re practically immune to any internal or external pressures and distractions that could hinder their performance.

You get into the flow state when you’re performing an activity you enjoy that you’re good at, but that also challenges you — as any good creative project does.

“[Creative people] have found the thing they love, but they’ve also built up the skill in it to be able to get into the flow state,” says Kaufman. “The flow state requires a match between your skill set and the task or activity you’re engaging in.”

They surround themselves with beauty.

Creatives tend to have excellent taste, and as a result, they enjoy being surrounded by beauty.

A study recently published in the journal Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts showed that musicians — including orchestra musicians, music teachers, and soloists — exhibit a high sensitivity and responsiveness to artistic beauty.

They connect the dots.

If there’s one thing that distinguishes highly creative people from others, it’s the ability to see possibilities where other don’t — or, in other words, vision. Many great artists and writers have said that creativity is simply the ability to connect the dots that others might never think to connect.

In the words of Steve Jobs:

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.”

They constantly shake things up.

Diversity of experience, more than anything else, is critical to creativity, says Kaufman. Creatives like to shake things up, experience new things, and avoid anything that makes life more monotonous or mundane.

“Creative people have more diversity of experiences, and habit is the killer of diversity of experience,” says Kaufman.

They make time for mindfulness.

Creative types understand the value of a clear and focused mind — because their work depends on it. Many artists, entrepreneurs, writers and other creative workers, such as David Lynch, have turned to meditation as a tool for tapping into their most creative state of mind.

And science backs up the idea that mindfulness really can boost your brain power in a number of ways. A 2012 Dutch study suggested that certain meditation techniques can promote creative thinking. And mindfulness practices have been linked with improved memory and focus, better emotional well-being, reduced stress and anxiety, and improved mental clarity — all of which can lead to better creative thought.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/04/creativity-habits_n_4859769.html