Key takeaways:

- Morning coffee drinkers had a 16% risk reduction for death from all causes.

- Morning coffee drinkers who consumed between over two to three or more cups achieved the greatest benefits.

People who drink coffee in the morning have a lower risk for death from all causes compared with those who do not drink coffee at all, results from an observational cohort study published in the European Heart Journal showed.

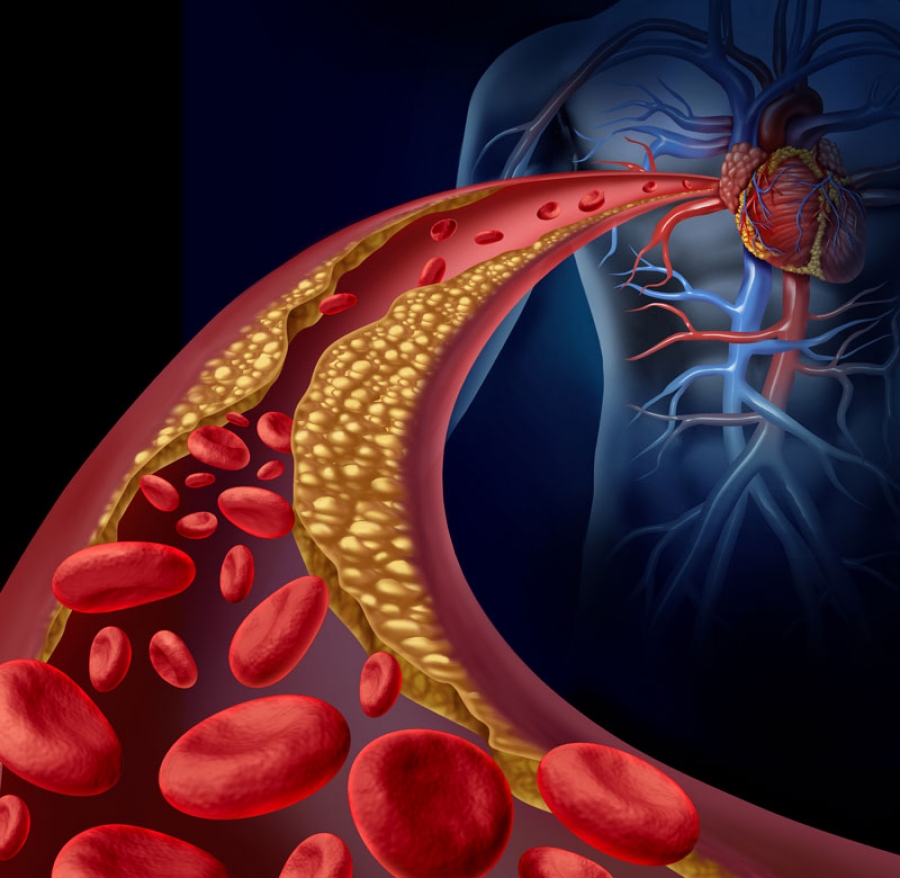

The association between morning coffee consumption and reduced mortality risk appeared especially strong with respect to CVD, according to researchers. Meanwhile, the analysis revealed that those who drank coffee throughout the day did not achieve the same mortality benefits as morning drinkers.

“While moderate coffee drinking has been recommended for the beneficial relations with health based on previous studies, primary care providers [should] be informed that the time of coffee drinking also matters, beyond the amounts consumed,” Lu Qi, MD, PhD, a professor at Tulane University Celia Scott Weatherhead School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, told Healio.

Current research suggests that coffee consumption “doesn’t raise the risk of cardiovascular disease, and it seems to lower the risk of some chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes,” Qi said in a press release.

“Given the effects that caffeine has on our bodies, we wanted to see if the time of day when you drink coffee has any impact on heart health.”

In the study, Qi and colleagues assessed links between mortality and coffee consumption — including the volume and timing — using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999 to 2018.

The analysis comprised 40,725 adults who had given dietary data of what they consumed on at least one day. This included a subgroup of 1,463 adults who completed a detailed food and drink diary for an entire week.

Overall, 48% of the cohort did not drink coffee, 36% had a morning-type coffee drinking pattern — primarily drinking from 4 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. — and 16% had an all-day drinking pattern.

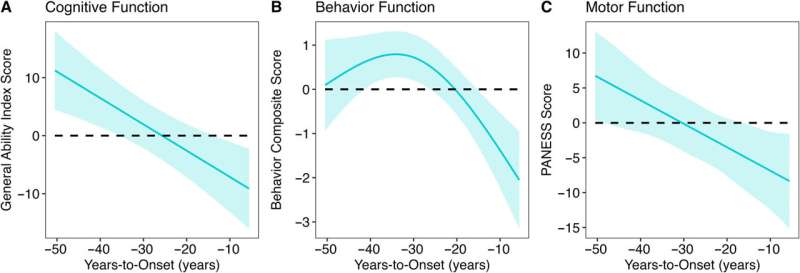

The researchers found that, after adjusting for factors like sleep hours and caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee intake amounts, morning coffee drinkers were 16% (HR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74-0.95) less likely to die of any cause and 31% (HR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.87) less likely to die from CVD compared with those who did not drink coffee.

People who drank coffee all day did not have any risk reductions vs. those who did not drink coffee.

The amount of coffee consumed among morning drinkers also influenced risk reductions, as researchers reported HRs for all-cause mortality of:

- 0.85 (95% CI, 0.71-1.01) among those who consumed more than zero to one cup;

- 0.84 (95% CI, 0.73-0.96) among those who consumed more than one to two cups;

- 0.72 (95% CI, 0.6-0.86) among those who consumed more than two to three cups; and

- 0.79 (95% CI, 0.65-0.97) among those who consumed more than three cups.

Study results showed similar patterns for mortality from CVD, “but the interaction term was not significant,” Qi and colleagues wrote.

The researchers identified a couple of study limitations. For example, the analysis used self-reported dietary data, opening the potential for recall bias, while they also could not rule out possible residual and unmeasured cofounders.

The study did not explain why morning coffee consumption reduced the risk for death from CVD, Qi said in the release.

“A possible explanation is that consuming coffee in the afternoon or evening may disrupt circadian rhythms and levels of hormones such as melatonin,” he said. “This, in turn, leads to changes in cardiovascular risk factors such as inflammation and [BP].”

Qi told Healio that regarding future research, “more studies are needed to investigate coffee drinking timing with other health outcomes, in different populations, and clinical trials would be helpful to provide evidence for causality.”

References:

- Morning coffee may protect the heart better than all-day coffee drinking. Available at:https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Press-Office/Press-releases/morning-coffee-may-protect-the-heart-better-than-all-day-coffee-drinking . Published Jan. 7, 2024. Accessed Jan. 10, 2024.

- Wang X, et al. Eur Heart J. et al. 2025;doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae871.