Workers have entered one of the most dangerous rooms at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation.

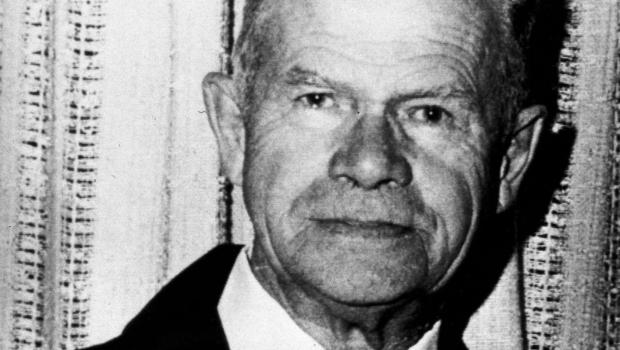

The so-called McCluskey Room in the Plutonium Finishing Plant is named after worker Harold McCluskey.

He was covered with radioactive material in 1976 when a glove box exploded. McCluskey, who was 64 at the time, lived for 11 more years and died from causes not related to the accident. He became known as the Atomic Man.

The room has largely been closed since the accident because of radioactivity. But workers are now proceeding with the final cleanup of the room as they get the Plutonium Finishing Plant ready for demolition.

Hanford, located near Richland, Washington, for decades made plutonium for nuclear weapons. The site is now engaged in cleaning up the resulting radioactive mess.

Cleaning up the McCluskey Room is expected to take a year.

A crew with contractor CH2M HILL Plateau Remediation Co. donned specially designed radiation suits before entering the McCluskey Room earlier this week. One of their first tasks was improving ventilation to better protect workers from airborne contamination as they clean out its equipment.

“This was the first of multiple entries workers will make to clean out processing equipment and get the McCluskey Room ready for demolition along with the rest of the plant,” said Bryan Foley, project director for the Department of Energy. “It has taken a year to prepare for this first entry.”

The room was used to recover americium – a plutonium byproduct – during the Cold War.

McCluskey was working in the room when a chemical reaction caused a glass glove box to explode. He was exposed to the highest dose of radiation from americium ever recorded – 500 times the occupational standard.

Covered with blood, McCluskey was dragged from the room and put into an ambulance headed for the decontamination center. Because he was too hot to handle, he was removed by remote control and transported to a steel-and-concrete isolation tank.

During the next five months, doctors extracted tiny bits of glass and razor-sharp pieces of metal embedded in his skin.

Nurses scrubbed him down three times a day and shaved every inch of his body every day. The radioactive bathwater and thousands of towels became nuclear waste.

McCluskey also received about 600 shots of zinc DTPA, an experimental drug that helped him excrete the radioactive material.

He was placed in isolation in a decontamination facility for five months. Within a year, his body’s radiation count had fallen by about 80 percent and he was allowed to return home.

Thanks to B.P. for bringing this to the attention of the It’s Interesting community.