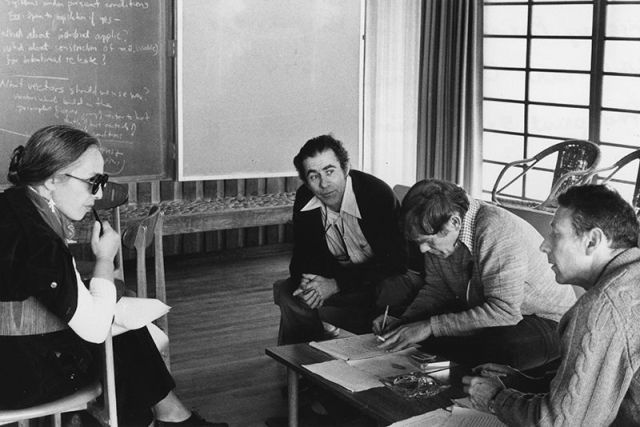

Kumar Alagramam. PhD, Case Western Reserve University

The ability to hear depends on proteins to reach the outer membrane of sensory cells in the inner ear. But in certain types of hereditary hearing loss, mutations in the protein prevent it from reaching these membranes. Using a zebrafish model, researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine have found that an anti-malarial drug called artemisinin may help prevent hearing loss associated with this genetic disorder.

In a recent study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers found the classic anti-malarial drug can help sensory cells of the inner ear recognize and transport an essential protein to specialized membranes using established pathways within the cell.

The sensory cells of the inner ear are marked by hair-like projections on the surface, earning them the nickname “hair cells.” Hair cells convert sound and movement-induced vibrations into electrical signals that are conveyed through nerves and translated in the brain as information used for hearing and balance.

The mutant form of the protein–clarin1–render hair cells unable to recognize and transport them to membranes essential for hearing using typical pathways within the cell. Instead, most mutant clarin1 proteins gets trapped inside hair cells, where they are ineffective and detrimental to cell survival. Faulty clarin1 secretion can occur in people with Usher syndrome, a common genetic cause of hearing and vision loss.

The study found artemisinin restores inner ear sensory cell function—and thus hearing and balance—in zebrafish genetically engineered to have human versions of an essential hearing protein.

Senior author on the study, Kumar N. Alagramam, the Anthony J. Maniglia Chair for Research and Education and associate professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine Department of Otolaryngology at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, has been studying ways to get mutant clarin1 protein to reach cell membranes to improve hearing in people with Usher syndrome.

“We knew mutant protein largely fails to reach the cell membrane, except patients with this mutation are born hearing,” Alagramam said. “This suggested to us that, somehow, at least a fraction of the mutant protein must get to cell membranes in the inner ear.”

Alagramam’s team searched for any unusual secretion pathways mutant clarin1 could take to get to hair cell membranes. “If we can understand how the human clarin1 mutant protein is transported to the membrane, then we can exploit that mechanism therapeutically,” Alagramam said.

For the PNAS study, Alagramam’s team created several new zebrafish models. They swapped the genes encoding zebrafish clarin1 with human versions—either normal clarin1, or clarin1 containing mutations found in humans with a type of Usher syndrome, which can lead to profound hearing loss.

“Using these ‘humanized’ fish models,” Alagramam said, “we were able to study the function of normal clarin1 and, more importantly, the functional consequences of its mutant counterpart. To our knowledge, this is the first time a human protein involved in hearing loss has been examined in this manner.”

Zebrafish offer several advantages to study hearing. Their larvae are transparent, making it easy to monitor inner ear cell shape and function. Their genes are also nearly identical to humans—particularly when it comes to genes that underlie hearing. Replacing zebrafish clarin1 with human clarin1 made an even more precise model.

The researchers found the unconventional cellular secretion pathway they were looking for by using florescent labels to track human clarin1 moving through zebrafish hair cells. The mutated clarin1 gets to the cell membrane using proteins and trafficking mechanisms within the cell, normally reserved for misfolded proteins “stuck” in certain cellular compartments.

“As far as we know, this is the first time a human mutant protein associated with hearing loss has been shown to be ‘escorted’ by the unconventional cellular secretion pathway,” Alagramam said. “This mechanism may shed light on the process underlying hearing loss associated with other mutant membrane proteins.”

The study showed the majority of mutant clarin1 gets trapped inside a network of tubules within the cell analogous to stairs and hallways helping proteins, including clarin1, get from place to place. Alagramam’s team surmised that liberating the mutant protein from this tubular network would be therapeutic and tested two drugs that target it: thapsigargin (an anti-cancer drug) and artemisinin (an anti-malarial drug).

The drugs did enable zebrafish larvae to liberate the trapped proteins and have higher clarin1 levels in the membrane; but artemisinin was the more effective of the two. Not only did the drug help mutant clarin1 to reach the membrane, hearing and balance functions were better preserved in zebrafish treated with the anti-malarial drug than untreated fish.

In zebrafish, survival depends on normal swim behavior, which in turn depends on balance and the ability to detect water movement, both of which are tied to hair cell function. Survival rates in zebrafish expressing the mutant clarin1 jumped from 5% to 45% after artemisinin treatment.

“Our report highlights the potential of artemisinin to mitigate both hearing and vision loss caused by clarin1 mutations,” Alagramam said. “This could be a re-purposable drug, with a safe profile, to treat Usher syndrome patients.”

Alagramam added that the unconventional secretion mechanism and the activation of that mechanism using artemisinin or similar drugs may also be relevant to other genetic disorders that involve mutant membrane proteins aggregating in the cell’s tubular network, including sensory and non-sensory disorders.

Gopal SR, et al. “Unconventional secretory pathway activation restores hair cell mechanotransduction in an USH3A model.” PNAS.

Drug to treat malaria could mitigate hereditary hearing loss