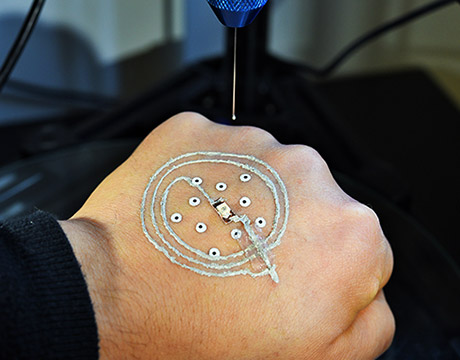

Zinnias such as this one were among the first flowers to be grown on the International Space Station.

Researchers on the International Space Station are growing plants in systems that may one day sustain astronauts traveling far across the solar system and beyond.

Vibrant orange flowers crown a leafy green stem. The plant is surrounded by many just like it, growing in an artificially lit greenhouse about the size of a laboratory vent hood. On Earth, these zinnias, colorful members of the daisy family, probably wouldn’t seem so extraordinary. But these blooms are literally out of this world. Housed on the International Space Station (ISS), orbiting 381 kilometers above Earth, they are among the first flowers grown in space and set the stage for the cultivation of all sorts of plants even farther from humanity’s home planet.

Coaxing this little flower to bloom wasn’t easy, Gioia Massa, a plant biologist at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, tells The Scientist. “Microgravity changes the way we grow plants.” With limited gravitational tug on them, plants aren’t sure which way to send their roots or shoots. They can easily dry out, too. In space, air and water don’t mix the way they do on Earth—liquid droplets glom together into large blobs that float about, instead of staying at the roots.

Massa is part of a group of scientists trying to overcome those challenges with a benchtop greenhouse called the Vegetable Production System, or Veggie. The system is a prototype for much larger greenhouses that could one day sustain astronauts on journeys to explore Mars. “As we’re looking to go deeper into space, we’re going to need ways to support astronaut crews nutritionally and cut costs financially,” says Matthew Romeyn, a long-duration food production scientist at Kennedy Space Center. “It’s a lot cheaper to send seeds than prepackaged food.”

In March 2014, Massa and colleagues developed “plant pillows”—small bags with fabric surfaces that contained a bit of soil and fertilizer in which to plant seeds. The bags sat atop a reservoir designed to wick water to the plants’ roots when needed (Open Agriculture, 2:33-41, 2017). At first, the ISS’s pillow-grown zinnias were getting too much water and turning moldy. After the crew ramped up the speed of Veggie’s fans, the flowers started drying out—an issue relayed to the scientists on the ground in 2015 by astronaut Scott Kelly, who took a special interest in the zinnias. Kelly suggested the astronauts water the plants by hand, just like a gardener would on Earth. A little injection of water into the pillows here and there, and the plants perked right up, Massa says.

With the zinnias growing happily, the astronauts began cultivating other flora, including cabbage, lettuce, and microgreens—shoots of salad vegetables—that they used to wrap their burgers and even to make imitation lobster rolls. The gardening helped to boost the astronauts’ diets, and also, anecdotally, brought them joy. “We’re just starting to study the psychological benefits of plants in space,” Massa says, noting that gardening has been shown to relieve stress. “If we’re going to have this opportunity available for longer-term missions, we have to start now.”

The team is currently working to make the greenhouses less dependent on people, as tending to plants during space missions might take astronauts away from more-critical tasks, Massa says. The researchers recently developed Veggie PONDS (Passive Orbital Nutrient Delivery System) with help from Techshot and Tupperware Brands Corporation. This system still uses absorbent mats to wick water to plants’ seeds and roots, but does so more consistently by evenly distributing the moisture. As a result, the crew shouldn’t have to keep such a close eye on the vegetation, and should be able to grow hard-to-cultivate garden plants, such as tomatoes and peppers. Time will tell. NASA sent Veggie PONDS to the ISS this past March, and astronauts are just now starting to compare the new system’s capabilities to those of Veggie.

“What they are doing on the ISS is really neat,” says astronomer Ed Guinan of the University of Pennsylvania. If astronauts are going to venture into deep space and be able to feed themselves, then they need to know how plants grow in environments other than Earth, and which grow best. The projects on the ISS will help answer those questions, he says. Guinan was so inspired by the ISS greenhouses he started his own project in 2017 studying how plants would grow in the soil of Mars—a likely future destination for manned space exploration. He ordered soil with characteristics of Martian dirt and told students in his astrobiology course, “You’re on Mars, there’s a colony there, and it’s your job to feed them.” Most of the students worked to grow nutritious plants, such as kale and other leafy greens, though one tried hops, a key ingredient in beer making. The hops, along with some of the other greens, grew well, Guinan reported at the American Astronomical Society meeting in January.

Yet, if and when astronauts go to Mars, they probably won’t be using the Red Planet’s dirt to grow food, notes Gene Giacomelli, a horticultural engineer at the University of Arizona. There are toxic chemicals called perchlorates to contend with, among other challenges, making it more probable that a Martian greenhouse will operate on hydroponics, similar to the systems being tested on the ISS. “The idea is to simplify things,” says Giacomelli, who has sought to design just such a greenhouse. “If you think about Martian dirt, we know very little about it—so do I trust it is going to be able to feed me, or do I take a system I know will feed me?”

For the past 10 years, Giacomelli has been working with others on a project, conceived by now-deceased business owner Phil Sadler, to build a self-regulating greenhouse that could support a crew of astronauts. This is not a benchtop system like you find on the space station, but a 5.5-meter-long, 2-meter-diameter cylinder that unfurls into an expansive greenhouse with tightly controlled circulation of air and water. The goal of the project, which was suspended in December due to lack of funding, was to show that the lab-size greenhouse could truly sustain astronauts. The greenhouse was only partially successful; the team calculated that a single cylinder would provide plenty of fresh drinking water, but would produce less than half the daily oxygen and calories an astronaut would need to survive a space mission. Though the project is on hold, Giacomelli says he hopes it will one day continue.

This kind of work, both here and on the ISS, is essential to someday sustaining astronauts in deep space, Giacomelli says. And, if researchers can figure out how to make such hydroponic systems efficient and waste-free, he notes, “the heck with Mars and the moon, we could bring that technology back to Earth.”