We may go to sleep at night, but our brains don’t. Instead, they spend those quiet hours tidying up, and one of their chores is to lug memories into long-term storage boxes.

Now, a group of scientists may have found a way to give that memory-storing process a boost, by delivering precisely timed electric zaps to the brain at the exact right moments of sleep. These zaps, the researchers found, can improve memory.

And to make matters even more interesting, the team of researchers was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the U.S. agency tasked with developing technology for the military. They reported their findings July 23 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

DARPA Wants to Zap Your Brain to Boost Your Memory

Credit: Shutterstock

We may go to sleep at night, but our brains don’t. Instead, they spend those quiet hours tidying up, and one of their chores is to lug memories into long-term storage boxes.

Now, a group of scientists may have found a way to give that memory-storing process a boost, by delivering precisely timed electric zaps to the brain at the exact right moments of sleep. These zaps, the researchers found, can improve memory.

And to make matters even more interesting, the team of researchers was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the U.S. agency tasked with developing technology for the military. They reported their findings July 23 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

If the findings are confirmed with additional research, the brain zaps could one day be used to help students study for a big exam, assist people at work or even treat patients with memory impairments, including those who experienced a traumatic brain injury in the military, said senior study author Praveen Pilly, a senior scientist at HRL Laboratories, a research facility focused on advancing technology.

The study involved 16 healthy adults from the Albuquerque, New Mexico, area. The first night, no experiments were run; instead, it was simply an opportunity for the participants to get accustomed to spending the night in the sleep lab while wearing the lumpy stimulation cap designed to deliver the tiny zaps to their brains. Indeed, when the researchers started the experiment, “our biggest worry [was] whether our subjects [could] sleep with all those wires,” Pilly told Live Science.

The next night, the experiment began: Before the participants fell asleep, they were shown war-like scenes and were asked to spot the location of certain targets, such as hidden bombs or snipers.

Then, the participants went to sleep, wearing the stimulation cap that not only delivered zaps but also measured brain activity using a device called an electroencephalogram (EEG). On the first night of the experiment, half of the participants received brain zaps, and half did not.

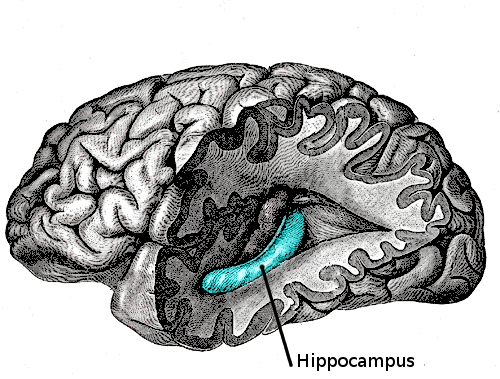

Using measurements from the EEG, the researchers aimed their electric zaps at a specific type of brain activity called “slow-wave oscillations.” These oscillations — which can be thought of as bursts of neuron activity that come and go with regularity — are known to be important for memory consolidation. They take place during two sleep stages: stage 2 (still a “light” sleep, when the heart rate slows down and body temperature drops) and stage 3 (deep sleep).

So, shortly after the participants in the zapping group fell into slow-wave oscillations, the stimulation cap would deliver slight zaps to the brain, in tune with the oscillations. The next morning, all of the participants were shown similar war-zone scenes, and the researchers measured how well they detected targets.

Five days later, the groups were switched for the second night of experiments.

The researchers found that, the mornings after, the participants who received the brain zaps weren’t any better at detecting targets in the same scene they saw the night before, compared with those who slept without zaps. But those who received the zapping were much better at detecting the same targets in novel scenes. For example, if the original scene showed a target under a rock, the “novel” scene might show the same target-rock image, but from a different angle, according to a press release from HRL Laboratories.

Researchers call this “generalization.” Pilly explained it as follows: “If you’re [studying] for a test, you learn a fact, and then, when you’re tested the following morning on the same fact … our intervention may not help you. On the other hand, if you’re tested on some questions related to that fact [but] which require you to generalize or integrate previous information,” the intervention would help you perform better.

This is because people rarely recall events exactly as they happen, Pilly said, referring to what’s known as episodic memory. Rather, people generalize what they learn and access that knowledge when faced with various situations. (For example, we know to stay away from a snake in the city, even if the first time we saw it, it was in the countryside.)

Previous studies have also investigated the effects of brain stimulation on memory. But although they delivered the zaps during the same sleep stage as the new study, the researchers in the previous studies didn’t attempt to match the zaps with the natural oscillations of the brain, Pilly said.

Jan Born, a professor of behavioral neuroscience at the University of Tübingen in Germany who was not part of the study, said the new research showed that, “at least in terms of behavior, [such a] procedure is effective.”

The approaches examined in the study have “huge potential, but we are still in the beginning [of this type of research], so we have to be cautious,” Born told Live Science.

One potential problem is that the stimulation typically hits the whole surface of the brain, Born said. Because the brain is wrinkled, and some neurons hide deep in the folds and others sit atop ridges, the stimulations aren’t very effective at targeting all of the neurons necessary, he said. This may make it difficult to reproduce the results every time, he added.

Pilly said that because the zaps aren’t specialized, they could also, in theory, lead to side effects. But he thinks, if anything, the side effect might simply be better-quality sleep.

https://www.livescience.com/63329-darpa-brain-zapping-memory.html

\

\