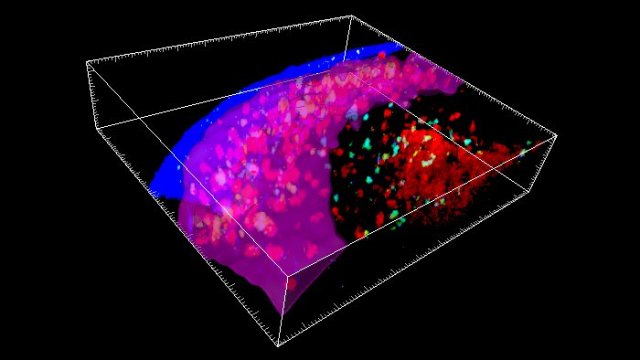

Diagram of the brain of a person with Alzheimer’s Disease.

In recent years, researchers have largely converged on the role of inflammation in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Studies over the past decade have revealed unexpected interactions between the brain and the immune system, and metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes may activate inflammatory responses that contribute to the development and progression of AD.

The activation of the inflammatory response is controlled by the inflammasome, a multi-protein oligomer that promotes the release of several pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and interleukin 18 (IL-18). In an earlier study, a group of researchers with the University of Massachusetts Medical School, the University of Tokyo and the University of Bonn reported that mice with a cognate of Alzheimer’s disease that were additionally bred to knock out the NLRP3 gene encoding the inflammasome were completely protected from neurodegenerative effects of the disease. The researchers presumed that this was the result of their inability to produce IL-1β and IL-18.

This finding was quite promising, suggesting that targeting components of the inflammasome might be a path to Alzheimer’s treatments. In their new study, they sought to determine the effect of IL-18 by breeding IL-18 knockout mice. The researchers considered IL-18 to be a promising target, because levels are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients with mild cognitive impairment. Additionally, it is known to increase the production of amyloid peptide.

But the result of the new mouse study was startling, and completely unprecedented in Alzheimer’s research. The IL-18 knockout mice developed a lethal seizure disorder that the researchers attribute to an increase in neuronal network transmission. The authors write, “… the effects of IL-18 deletion were so dramatic that we were unable to identify previous evidence to help understand the phenomena.”

The finding that a proinflammatory cytokine might in some way ameliorate seizure-inducing neural activity seems counterintuitive, since inflammation is theorized to promote neurodegenerative symptoms in AD. The researchers believe that epilepsy is understudied in AD patients, even though it is a common complication; they point out that two-thirds of AD patients experience both motor and non-motor seizures. Additionally, AD patients with epilepsy are more likely to develop memory loss and other cognitive symptoms, and experience a more widespread loss of brain cells than AD patients without epilepsy, according to the researchers.

They theorize that IL-18 may be counteracting seizure-promoting effects of IL-1β, and suppressing IL-18 thus induced seizures in the test mice. “In fact,” they write, “the countereffect of IL-18 and IL-1β has been documented in a mouse model of cerebellar ataxia. Importantly, we found that the acute application of IL-18 protein reduced excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, providing evidence that IL-18 has a protective function in neuronal excitability. Thus, we speculate that IL-18 directly suppresses these proepileptogenic effects of IL-1β in APP/PS1 mice.”

However, the most important implication of the study may be that, while the inflammasome is a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s, inhibiting specific cytokines could negatively affect people with the disease.

More information: Inflammasome-derived cytokine IL18 suppresses amyloid-induced seizures in Alzheimer-prone mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2018). doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801802115

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the progressive destruction and dysfunction of central neurons. AD patients commonly have unprovoked seizures compared with age-matched controls. Amyloid peptide-related inflammation is thought to be an important aspect of AD pathogenesis. We previously reported that NLRP3 inflammasome KO mice, when bred into APPswe/PS1ΔE9 (APP/PS1) mice, are completely protected from amyloid-induced AD-like disease, presumably because they cannot produce mature IL1β or IL18. To test the role of IL18, we bred IL18KO mice with APP/PS1 mice. Surprisingly, IL18KO/APP/PS1 mice developed a lethal seizure disorder that was completely reversed by the anticonvulsant levetiracetam. IL18-deficient AD mice showed a lower threshold in chemically induced seizures and a selective increase in gene expression related to increased neuronal activity. IL18-deficient AD mice exhibited increased excitatory synaptic proteins, spine density, and basal excitatory synaptic transmission that contributed to seizure activity. This study identifies a role for IL18 in suppressing aberrant neuronal transmission in AD.

Journal reference: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences