The purpose and evolutionary origins of sleep are among the biggest mysteries in neuroscience. Every complex animal, from the humblest fruit fly to the largest blue whale, sleeps — yet scientists can’t explain why any organism would leave itself vulnerable to predators, and unable to eat or mate, for a large portion of the day. Now, researchers have demonstrated for the first time that even an organism without a brain — a kind of jellyfish — shows sleep-like behaviour, suggesting that the origins of sleep are more primitive than thought.

Researchers observed that the rate at which Cassiopea jellyfish pulsed their bell decreased by one-third at night, and the animals were much slower to respond to external stimuli such as food or movement during that time. When deprived of their night-time rest, the jellies were less active the next day.

“Everyone we talk to has an opinion about whether or not jellyfish sleep. It really forces them to grapple with the question of what sleep is,” says Ravi Nath, the paper’s first author and a molecular geneticist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. The study was published in Current Biology.

“This work provides compelling evidence for how early in evolution a sleep-like state evolved,” says Dion Dickman, a neuroscientist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Mindless sleep

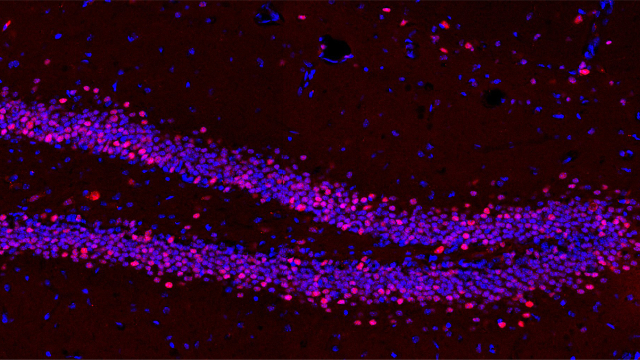

Nath is studying sleep in the worm Caenorhabditis elegans, but whenever he presented his work at research conferences, other scientists scoffed at the idea that such a simple animal could sleep. The question got Nath thinking: how minimal can an animal’s nervous system get before the creature lacks the ability to sleep? Nath’s obsession soon infected his friends and fellow Caltech PhD students Michael Abrams and Claire Bedbrook. Abrams works on jellyfish, and he suggested that one of these creatures would be a suitable model organism, because jellies have neurons but no central nervous system. Instead, their neurons connect in a decentralized neural net.

Cassiopea jellyfish, in particular, caught the trio’s attention. Nicknamed the upside-down jellyfish because of its habit of sitting on the sea floor on its bell, with its tentacles waving upwards, Cassiopea rarely moves on its own. This made it easier for the researchers to design an automated system that used video to track the activity of the pulsing bell. To provide evidence of sleep-like behaviour in Cassiopea (or any other organism), the researchers needed to show a rapidly reversible period of decreased activity, or quiescence, with decreased responsiveness to stimuli. The behaviour also had to be driven by a need to sleep that increased the longer the jellyfish was awake, so that a day of reduced sleep would be followed by increased rest.

Other researchers had already documented a nightly drop in activity in other species of jellyfish, but no jellyfish had been known to display the other aspects of sleep behaviour. In a 35-litre tank, Nath, Abrams and Bedbrook tracked the bell pulses of Cassiopea over six days and nights and found that the rate, which was an average of one pulse per second by day, dropped by almost one-third at night. They also documented night-time pulse-free periods of 10–15 seconds, which didn’t occur during the day.

Restless night

Without an established jellyfish alarm clock, the scientists used a snack of brine shrimp and oyster roe to try to rouse the snoozing Cassiopea. When they dropped food in the tank at night, Cassiopea responded to its treat by returning to a daytime pattern of activity. The team used the jellyfish’s preference for sitting on solid surfaces to test whether quiescent Cassiopea had a delayed response to external stimuli. They slowly lifted the jellyfish off the bottom of the tank using a screen, then pulled it out from under the animal, leaving the jelly floating in the water. It took longer for the creature to begin pulsing and to reorient itself when this happened at night than it did during the day. If the experiment was immediately repeated at night, the jellyfish responded as if it were daytime. Lastly, when the team forced Cassiopea to pull an all-nighter by keeping it awake with repeated pulses of water, they found a 17% drop in activity the following day.

“This work shows that sleep is much older than we thought. The simplicity of these organisms is a door opener to understand why sleep evolved and what it does,” says Thomas Bosch, an evolutionary biologist at Kiel University in Germany. “Sleep can be traced back to these little metazoans — how much further does it go?” he asks.

That’s what Nath, Abrams and Bedbrook want to find out. Amid the chaos of finishing their PhD theses, they have begun searching for ancient genes that might control sleep, in the hope that this might provide hints as to why sleep originally evolved.

https://www.nature.com/news/jellyfish-caught-snoozing-give-clues-to-origin-of-sleep-1.22654