A 3-D rendering of the serotonin system in the left hemisphere of the mouse brain reveals two groups of serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe that project to either cortical regions (blue) or subcortical regions (green) while rarely crossing into the other’s domain.

As Liqun Luo was writing his introductory textbook on neuroscience in 2012, he found himself in a quandary. He needed to include a section about a vital system in the brain controlled by the chemical messenger serotonin, which has been implicated in everything from mood to movement regulation. But the research was still far from clear on what effect serotonin has on the mammalian brain.

“Scientists were reporting divergent findings,” said Luo, who is the Ann and Bill Swindells Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford University. “Some found that serotonin promotes pleasure. Another group said that it increases anxiety while suppressing locomotion, while others argued the opposite.”

Fast forward six years, and Luo’s team thinks it has reconciled those earlier confounding results. Using neuroanatomical methods that they invented, his group showed that the serotonin system is actually composed of at least two, and likely more, parallel subsystems that work in concert to affect the brain in different, and sometimes opposing, ways. For instance, one subsystem promotes anxiety, whereas the other promotes active coping in the face of challenges.

“The field’s understanding of the serotonin system was like the story of the blind men touching the elephant,” Luo said. “Scientists were discovering distinct functions of serotonin in the brain and attributing them to a monolithic serotonin system, which at least partly accounts for the controversy about what serotonin actually does. This study allows us to see different parts of the elephant at the same time.”

The findings, published online on August 23 in the journal Cell, could have implications for the treatment of depression and anxiety, which involves prescribing drugs such as Prozac that target the serotonin system – so-called SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). However, these drugs often trigger a host of side effects, some of which are so intolerable that patients stop taking them.

“If we can target the relevant pathways of the serotonin system individually, then we may be able to eliminate the unwanted side effects and treat only the disorder,” said study first author Jing Ren, a postdoctoral fellow in Luo’s lab.

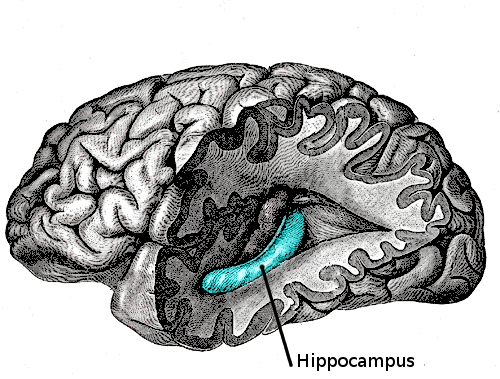

Organized projections of neurons

The Stanford scientists focused on a region of the brainstem known as the dorsal raphe, which contains the largest single concentration in the mammalian brain of neurons that all transmit signals by releasing serotonin (about 9,000).

The nerve fibers, or axons, of these dorsal raphe neurons send out a sprawling network of connections to many critical forebrain areas that carry out a host of functions, including thinking, memory, and the regulation of moods and bodily functions. By injecting viruses that infect serotonin axons in these regions, Ren and her colleagues were able to trace the connections back to their origin neurons in the dorsal raphe.

This allowed them to create a visual map of projections between the dense concentration of serotonin-releasing neurons in the brainstem to the various regions of the forebrain that they influence. The map revealed two distinct groups of serotonin-releasing neurons in the dorsal raphe, which connected to cortical and subcortical regions in the brain.

“Serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe project to a bunch of places throughout the brain, but those bunches of places are organized,” Luo said. “That wasn’t known before.”

Two parts of the elephant

In a series of behavioral tests, the scientists also showed that serotonin neurons from the two groups can respond differently to stimuli. For example, neurons in both groups fired in response to mice receiving rewards like sips of sugar water but they showed opposite responses to punishments like mild foot shocks.

“We now understand why some scientists thought serotonin neurons are activated by punishment, while others thought it was inhibited by punishment. Both are correct – it just depends on which subtype you’re looking at,” Luo said.

What’s more, the group found that the serotonin neurons themselves were more complex than originally thought. Rather than just transmitting messages with serotonin, the cortical-projecting neurons also released a chemical messenger called glutamate – making them one of the few known examples of neurons in the brain that release two different chemicals.

“It raises the question of whether we should even be calling these serotonin neurons because neurons are named after the neurotransmitters they release,” Ren said.

Taken together, these findings indicate that the brain’s serotonin system is not made up of a homogenous population of neurons but rather many subpopulations acting in concert. Luo’s team has identified two groups, but there could be many others.

In fact, Robert Malenka, a professor and associate chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford’s School of Medicine, and his team recently discovered a group of serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe that project to the nucleus accumbens, the part of the brain that promotes social behaviors.

“The two groups that we found don’t send axons to the nucleus accumbens, so this is clearly a third group,” Luo said. “We identified two parts of the elephant, but there are more parts to discover.”

\

\