By Ben Turner

For the first time ever, physicists have captured a clear image of individual atoms behaving like a wave.

The image shows sharp red dots of fluorescing atoms transforming into fuzzy blobs of wave packets and is a stunning demonstration of the idea that atoms exist as both particles and waves — one of the cornerstones of quantum mechanics.

The scientists who invented the imaging technique published their findings on the preprint server arXiv, so their research has not yet been peer reviewed.

“The wave nature of matter remains one of the most striking aspects of quantum mechanics,” the researchers wrote in the paper. They add that their new technique could be used to image more complex systems, giving insights into some fundamental questions in physics.

First proposed by the French physicist Louis de Broglie in 1924 and expanded upon by Erwin Schrödinger two years later, wave particle duality states that all quantum-sized objects, and therefore all matter, exists as both particles and waves at the same time.

Schrödinger’s famous equation is typically interpreted by physicists as stating that atoms exist as packets of wave-like probability in space, which are then collapsed into discrete particles upon observation. While bafflingly counterintuitive, this bizarre property of the quantum world has been witnessed in numerous experiments.

To image this fuzzy duality, the physicists first cooled lithium atoms to near-absolute zero temperatures by bombarding them with photons, or light particles, from a laser to rob them of their momentum. Once the atoms were cooled, more lasers trapped them within an optical lattice as discrete packets.

With the atoms cooled and confined, the researchers periodically switched the optical lattice off and on — expanding the atoms from a confined near-particle state to one resembling a wave, and then back.

A microscope camera recorded light emitted by atoms in the particle state at two different times, with atoms behaving like waves in between. By putting together many images, the authors built up the shape of this wave and observed how it expands with time, in perfect agreement with Schrödinger’s equation

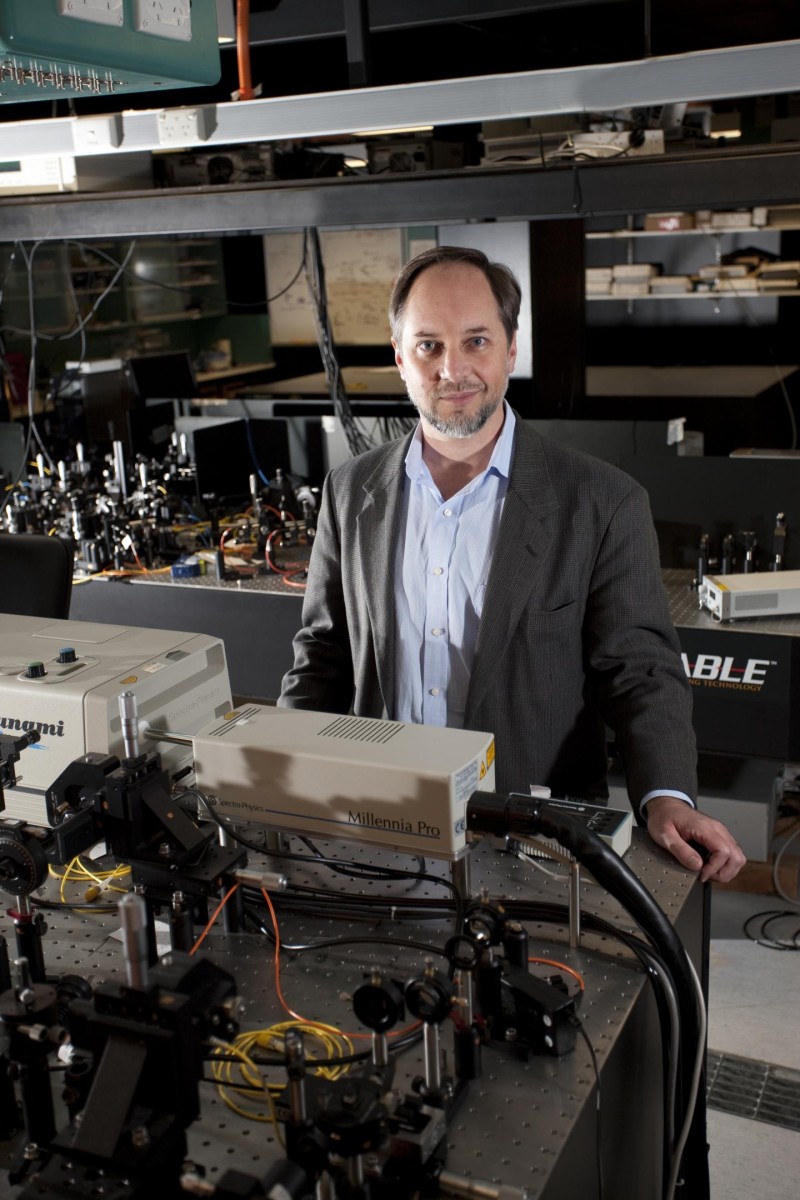

“This imaging method consists in turning back on the lattice to project each wave packet into a single well to turn them into a particle again — it is not a wave anymore,” study co-author Tarik Yefsah, a physicist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and the École normale supérieure in Paris, told Live Science. “You can see our imaging method as a way to sample the wavefunction density, not unlike the pixels of a CCD camera.” A CCD camera is a common type of digital camera that uses a charge-coupled device to capture its images.

The scientists say this image is just a simple demonstration. Their next step will be using it to study systems of strongly interacting atoms that are less well understood.

“Studying such systems could improve our understanding of strange states of matter, such as those found in the core of extremely dense neutron stars, or the quark-gluon plasma that is believed to have existed shortly after the Big Bang,” Yefsah said.