By Nicoletta Lanese

Humans spend about a third of our lives sleeping, and scientists have long debated why slumber takes up such a huge slice of our time. Now, a new study hints that our main reason for sleeping starts off as one thing, then changes at a surprisingly specific age.

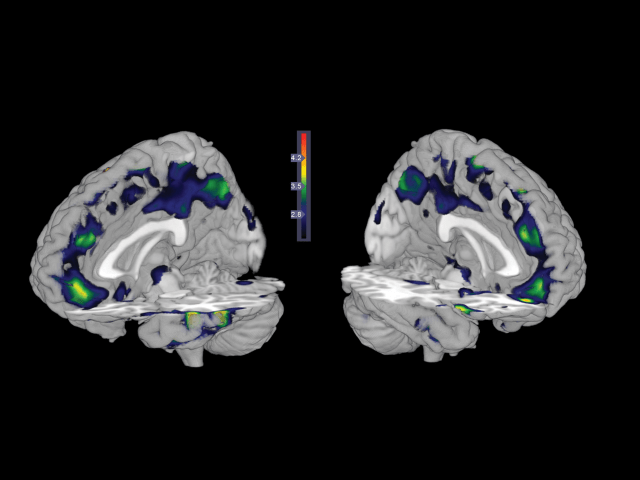

Two leading theories as to why we sleep focus on the brain: One theory says that the brain uses sleep to reorganize the connections between its cells, building electrical networks that support our memory and ability to learn; the other theory says that the brain needs time to clean up the metabolic waste that accumulates throughout the day. Neuroscientists have quibbled over which of these functions is the main reason for sleep, but the new study reveals that the answer may be different for babies and adults.

In the study, published Sep. 18 in the journal Science Advances, researchers use a mathematical model to show that infants spend most of their sleeping hours in “deep sleep,” also known as random eye movement (REM) sleep, while their brains rapidly build new connections between cells and grow ever larger. Then, just before toddlers reach age 2-and-a-half, their amount of REM sleep dips dramatically as the brain switches into maintenance mode, mostly using sleep time for cleaning and repair.

“It was definitely shocking to us that this transition was so sharp,” from growth mode to maintenance mode, senior author Van Savage, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and of computational medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles and the Santa Fe Institute, told Live Science in an email. The researchers also collected data in other mammals — namely rabbits, rats and guinea pigs — and found that their sleep might undergo a similar transformation; however, it’s too soon to tell whether these patterns are consistent across many species.

That said, “I think in actuality, it may not be really so sharp” a transition, said Leila Tarokh, a neuroscientist and Group Leader at the University Hospital of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University of Bern, who was not involved in the study. The pace of brain development varies widely between individuals, and the researchers had fairly “sparse” data points between the ages of 2 and 3, she said. If they studied individuals through time as they aged, they might find that the transition is less sudden and more smooth, or the age of transition may vary between individuals, she said.

An emerging hypothesis

In a previous study, published in 2007 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Savage and theoretical physicist Geoffrey West found that an animal’s brain size and brain metabolic rate accurately predict the amount of time the animal sleeps — more so than the animal’s overall body size. In general, big animals with big brains and low brain metabolic rates sleep less than small animals with the opposite features.

This rule holds up across different species and between members of the same species; for instance, mice sleep more than elephants, and newborn babies sleep more than adult humans. However, knowing that sleep time decreases as brains get bigger, the authors wondered how quickly that change occurs in different animals, and whether that relates to the function of sleep over time.

To begin answering these questions, the researchers pooled existing data on how much humans sleep, compiling several hundred data points from newborn babies and children up to age 15. They also gathered data on brain size and metabolic rate, the density of connections between brain cells, body size and metabolic rate, and the ratio of time spent in REM sleep versus non-REM sleep at different ages; the researchers drew these data points from more than 60 studies, overall.

Babies sleep about twice as much as adults, and they spend a larger proportion of their sleep time in REM, but there’s been a long-standing question as to what function that serves, Tarokh noted.

The study authors built a mathematical model to track all these shifting data points through time and see what patterns emerged between them. They found that the metabolic rate of the brain was high during infancy when the organ was building many new connections between cells, and this in turn correlated with more time spent in REM sleep. They concluded that the long hours of REM in infancy support rapid remodeling in the brain, as new networks form and babies pick up new skills. Then, between age 2 and 3, “the connections are not changing nearly as quickly,” and the amount of time spent in REM diminishes, Savage said.

At this time, the metabolic rate of cells in the cerebral cortex — the wrinkled surface of the brain — also changes. In infancy, the metabolic rate is proportional to the number of existing connections between brain cells plus the energy needed to fashion new connections in the network. As the rate of construction slows, the relative metabolic rate slows in turn.

“In the first few years of life, you see that the brain is making tons of new connections … it’s blossoming, and that’s why we see all those skills coming on,” Tarokh said. Developmental psychologists refer to this as a “critical period” of neuroplasticity — the ability of the brain to forge new connections between its cells. “It’s not that plasticity goes away” after that critical period, but the construction of new connections slows significantly, as the new mathematical model suggests, Tarokh said. At the same time, the ratio of non-REM to REM sleep increases, supporting the idea that non-REM is more important to brain maintenance than neuroplasticity.

Looking forward, the authors plan to apply their mathematical model of sleep to other animals, to see whether a similar switch from reorganization to repair occurs early in development, Savage said.

“Humans are known to be unusual in the amount of brain development that occurs after birth,” lead author Junyu Cao, an assistant professor in the Department of Information, Risk, and Operations Management at The University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science in an email. (Cao played a key role in compiling data and performing computations for the report.) “Therefore, it is conceivable that the phase transition described here for humans may occur earlier in other species, possibly even before birth.”

In terms of human sleep, Tarokh noted that different patterns of electrical activity, known as oscillations, occur in REM versus non-REM sleep; future studies could reveal whether and how particular oscillations shape the brain as we age, given that the amount of time spent in REM changes, she said. Theoretically, disruptions in these patterns could contribute to developmental disorders that emerge in infancy and early childhood, she added — but again, that’s just a hypothesis.