Life and death are traditionally viewed as opposites. But the emergence of new multicellular life-forms from the cells of a dead organism introduces a “third state” that lies beyond the traditional boundaries of life and death.

Usually, scientists consider death to be the irreversible halt of functioning of an organism as a whole. However, practices such as organ donation highlight how organs, tissues and cells can continue to function even after an organism’s demise. This resilience raises the question: What mechanisms allow certain cells to keep working after an organism has died?

We are researchers who investigate what happens within organisms after they die. In our recently published review, we describe how certain cells – when provided with nutrients, oxygen, bioelectricity or biochemical cues – have the capacity to transform into multicellular organisms with new functions after death.

Life, death and emergence of something new

The third state challenges how scientists typically understand cell behavior. While caterpillars metamorphosing into butterflies, or tadpoles evolving into frogs, may be familiar developmental transformations, there are few instances where organisms change in ways that are not predetermined. Tumors, organoids and cell lines that can indefinitely divide in a petri dish, like HeLa cells, are not considered part of the third state because they do not develop new functions.

However, researchers found that skin cells extracted from deceased frog embryos were able to adapt to the new conditions of a petri dish in a lab, spontaneously reorganizing into multicellular organisms called xenobots. These organisms exhibited behaviors that extend far beyond their original biological roles. Specifically, these xenobots use their cilia – small, hair-like structures – to navigate and move through their surroundings, whereas in a living frog embryo, cilia are typically used to move mucus.

Xenobots are also able to perform kinematic self-replication, meaning they can physically replicate their structure and function without growing. This differs from more common replication processes that involve growth within or on the organism’s body.

Researchers have also found that solitary human lung cells can self-assemble into miniature multicellular organisms that can move around. These anthrobots behave and are structured in new ways. They are not only able to navigate their surroundings but also repair both themselves and injured neuron cells placed nearby.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate the inherent plasticity of cellular systems and challenge the idea that cells and organisms can evolve only in predetermined ways. The third state suggests that organismal death may play a significant role in how life transforms over time.

Postmortem conditions

Several factors influence whether certain cells and tissues can survive and function after an organism dies. These include environmental conditions, metabolic activity and preservation techniques.

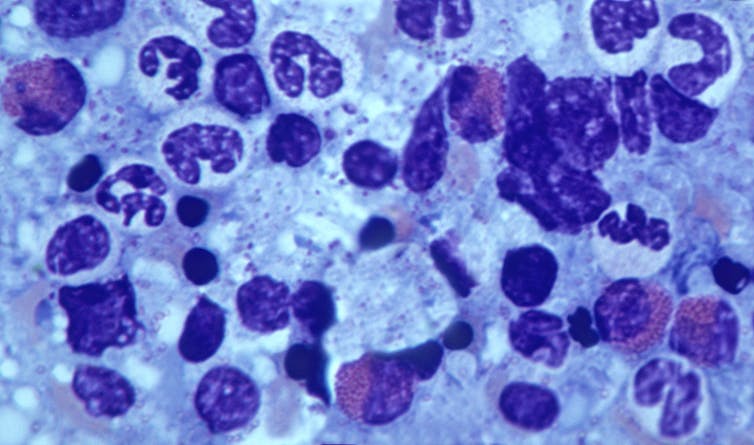

Different cell types have varying survival times. For example, in humans, white blood cells die between 60 and 86 hours after organismal death. In mice, skeletal muscle cells can be regrown after 14 days postmortem, while fibroblast cells from sheep and goats can be cultured up to a month or so postmortem.

Metabolic activity plays an important role in whether cells can continue to survive and function. Active cells that require a continuous and substantial supply of energy to maintain their function are more difficult to culture than cells with lower energy requirements. Preservation techniques such as cryopreservation can allow tissue samples such as bone marrow to function similarly to that of living donor sources.

Inherent survival mechanisms also play a key role in whether cells and tissues live on. For example, researchers have observed a significant increase in the activity of stress-related genes and immune-related genes after organismal death, likely to compensate for the loss of homeostasis. Moreover, factors such as trauma, infection and the time elapsed since death significantly affect tissue and cell viability.

Factors such as age, health, sex and type of species further shape the postmortem landscape. This is seen in the challenge of culturing and transplanting metabolically active islet cells, which produce insulin in the pancreas, from donors to recipients. Researchers believe that autoimmune processes, high energy costs and the degradation of protective mechanisms could be the reason behind many islet transplant failures.

How the interplay of these variables allows certain cells to continue functioning after an organism dies remains unclear. One hypothesis is that specialized channels and pumps embedded in the outer membranes of cells serve as intricate electrical circuits. These channels and pumps generate electrical signals that allow cells to communicate with each other and execute specific functions such as growth and movement, shaping the structure of the organism they form.

The extent to which different types of cells can undergo transformation after death is also uncertain. Previous research has found that specific genes involved in stress, immunity and epigenetic regulation are activated after death in mice, zebrafish and people, suggesting widespread potential for transformation among diverse cell types.

Implications for biology and medicine

The third state not only offers new insights into the adaptability of cells. It also offers prospects for new treatments.

For example, anthrobots could be sourced from an individual’s living tissue to deliver drugs without triggering an unwanted immune response. Engineered anthrobots injected into the body could potentially dissolve arterial plaque in atherosclerosis patients and remove excess mucus in cystic fibrosis patients.

Importantly, these multicellular organisms have a finite life span, naturally degrading after four to six weeks. This “kill switch” prevents the growth of potentially invasive cells.

A better understanding of how some cells continue to function and metamorphose into multicellular entities some time after an organism’s demise holds promise for advancing personalized and preventive medicine.