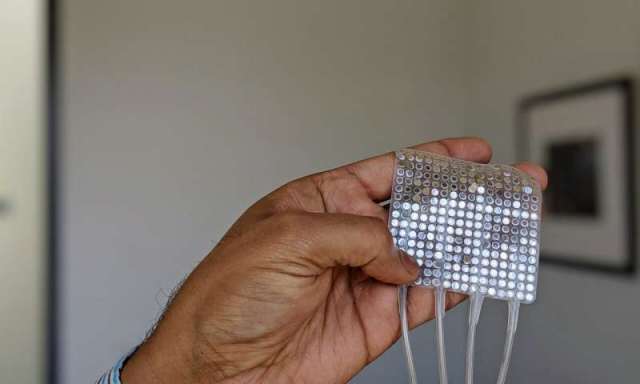

A mouse exploring one of the custom hologram generators used in the experiments at Stanford. By stimulating particular neurons, scientists were able to make engineered mice see visual patterns that weren’t there.

By Carl Zimmer

In a laboratory at the Stanford University School of Medicine, the mice are seeing things. And it’s not because they’ve been given drugs.

With new laser technology, scientists have triggered specific hallucinations in mice by switching on a few neurons with beams of light. The researchers reported the results on Thursday in the journal Science.

The technique promises to provide clues to how the billions of neurons in the brain make sense of the environment. Eventually the research also may lead to new treatments for psychological disorders, including uncontrollable hallucinations.

“This is spectacular — this is the dream,” said Lindsey Glickfeld, a neuroscientist at Duke University, who was not involved in the new study.

In the early 2000s, Dr. Karl Deisseroth, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist at Stanford, and other scientists engineered neurons in the brains of living mouse mice to switch on when exposed to a flash of light. The technique is known as optogenetics.

In the first wave of these experiments, researchers used light to learn how various types of neurons worked. But Dr. Deisseroth wanted to be able to pick out any individual cell in the brain and turn it on and off with light.

So he and his colleagues designed a new device: Instead of just bathing a mouse’s brain in light, it allowed the researchers to deliver tiny beams of red light that could strike dozens of individual brain neurons at once.

To try out this new system, Dr. Deisseroth and his colleagues focused on the brain’s perception of the visual world. When light enters the eyes — of a mouse or a human — it triggers nerve endings in the retina that send electrical impulses to the rear of the brain.

There, in a region called the visual cortex, neurons quickly detect edges and other patterns, which the brain then assembles into a picture of reality.

The scientists inserted two genes into neurons in the visual cortices of mice. One gene made the neurons sensitive to the red laser light. The other caused neurons to produce a green flash when turned on, letting the researchers track their activity in response to stimuli.

The engineered mice were shown pictures on a monitor. Some were of vertical stripes, others of horizontal stripes. Sometimes the stripes were bright, sometimes fuzzy. The researchers trained the mice to lick a pipe only if they saw vertical stripes. If they performed the test correctly, they were rewarded with a drop of water.

As the mice were shown images, thousands of neurons in their visual cortices flashed green. One population of cells switched on in response to vertical stripes; other neurons flipped on when the mice were shown horizontal ones.

The researchers picked a few dozen neurons from each group to target. They again showed the stripes to the mice, and this time they also fired light at the neurons from the corresponding group. Switching on the correct neurons helped the mice do better at recognizing stripes.

Then the researchers turned off the monitor, leaving the mice in darkness. Now the scientists switched on the neurons for horizontal and vertical stripes, without anything for the rodents to see. The mice responded by licking the pipe, as if they were actually seeing vertical stripes.

Anne Churchland, a neuroscientist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory who was not involved in the study, cautioned that this kind of experiment can’t reveal much about a mouse’s inner experience.

“It’s not like a creature can tell you, ‘Oh, wow, I saw a horizontal bar,’” she said.

Dr. Churchland said that it would take more research to better understand why the mice behaved as they did in response to the flashes of red light. Did they see the horizontal stripes more clearly, or were they less distracted by misleading signals?

One of the most remarkable results from the study came about when Dr. Deisseroth and his colleagues narrowed their beams of red light to fewer and fewer neurons. They kept getting the mice to lick the pipe as if they were seeing the vertical stripes.

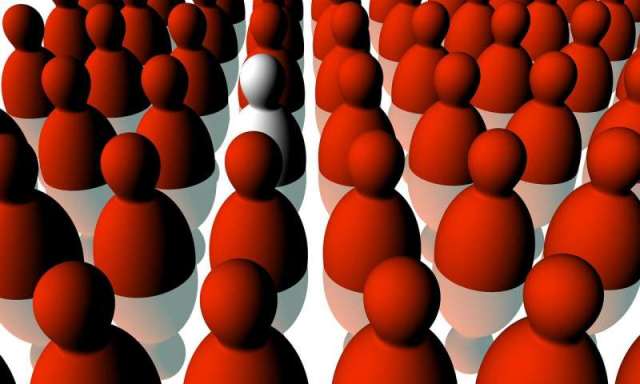

In the end, the scientists found they could trigger the hallucinations by stimulating as few as two neurons. Thousands of other neurons in the visual cortex would follow the lead of those two cells, flashing green as they became active.

Clusters of neurons in the brain may be tuned so that they’re ready to fire at even a slight stimulus, Dr. Deisseroth and his colleagues concluded — like a snowbank poised to become an avalanche.

But it doesn’t take a fancy optogenetic device to make a few neurons fire. Even when they’re not receiving a stimulus, neurons sometimes just fire at random.

That raises a puzzle: If all it takes is two neurons, why are we not hallucinating all the time?

Maybe our brain wiring prevents it, Dr. Deisseroth said. When a neuron randomly fires, others may send signal it to quiet down.

Dr. Glickfeld speculated that attention may be crucial to triggering the avalanche of neuronal action only at the right times. “Attention allows you to ignore a lot of the background activity,” she said.

Dr. Deisseroth hopes to see what other hallucinations he can trigger with light. In other parts of the brain, he might be able to cause mice to perceive more complex images, such as the face of a cat. He might be able to coax neurons to create phantom sounds, or even phantom smells.

As a psychiatrist, Dr. Deisseroth has treated patients who have suffered from visual hallucinations. In his role as a neuroscientist, he’d like to find out more about how individual neurons give rise to these images — and how to stop them.

“Now we know where those cells are, what they look like, what their shape is,” he said. “In future work, we can get to know them in much more detail.”