by BRET STETKA

Dr. Leslie Norins is willing to hand over $1 million of his own money to anyone who can clarify something: Is Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia worldwide, caused by a germ?

By “germ” he means microbes like bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. In other words, Norins, a physician turned publisher, wants to know if Alzheimer’s is infectious.

It’s an idea that just a few years ago would’ve seemed to many an easy way to drain your research budget on bunk science. Money has poured into Alzheimer’s research for years, but until very recently not much of it went toward investigating infection in causing dementia.

But this “germ theory” of Alzheimer’s, as Norins calls it, has been fermenting in the literature for decades. Even early 20th century Czech physician Oskar Fischer — who, along with his German contemporary Dr. Alois Alzheimer, was integral in first describing the condition — noted a possible connection between the newly identified dementia and tuberculosis.

If the germ theory gets traction, even in some Alzheimer’s patients, it could trigger a seismic shift in how doctors understand and treat the disease.

For instance, would we see a day when dementia is prevented with a vaccine, or treated with antibiotics and antiviral medications? Norins thinks it’s worth looking into.

Norins received his medical degree from Duke in the early 1960s, and after a stint at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention he fell into a lucrative career in medical publishing. He eventually settled in an admittedly aged community in Naples, Fla., where he took an interest in dementia and began reading up on the condition.

After scouring the medical literature he noticed a pattern.

“It appeared that many of the reported characteristics of Alzheimer’s disease were compatible with an infectious process,” Norins tells NPR. “I thought for sure this must have already been investigated, because millions and millions of dollars have been spent on Alzheimer’s research.”

But aside from scattered interest through the decades, this wasn’t the case.

In 2017, Norins launched Alzheimer’s Germ Quest Inc., a public benefit corporation he hopes will drive interest into the germ theory of Alzheimer’s, and through which his prize will be distributed. A white paper he penned for the site reads: “From a two-year review of the scientific literature, I believe it’s now clear that just one germ — identity not yet specified, and possibly not yet discovered — causes most AD. I’m calling it the ‘Alzheimer’s Germ.’ ”

Norins is quick to cite sources and studies supporting his claim, among them a 2010 study published in the Journal of Neurosurgery showing that neurosurgeons die from Alzheimer’s at a nearly 2 1/2 times higher rate than they do from other disorders.

Another study from that same year, published in The Journal of the American Geriatric Society, found that people whose spouses have dementia are at a 1.6 times greater risk for the condition themselves.

Contagion does come to mind. And Norins isn’t alone in his thinking.

In 2016, 32 researchers from universities around the world signed an editorial in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease calling for “further research on the role of infectious agents in [Alzheimer’s] causation.” Based on much of the same evidence Norins encountered, the authors concluded that clinical trials with antimicrobial drugs in Alzheimer’s are now justified.

NPR reported on an intriguing study published in Neuron in June that suggested that viral infection can influence the progression of Alzheimer’s. Led by Mount Sinai genetics professor Joel Dudley, the work was intended to compare the genomes of healthy brain tissue with that affected by dementia.

But something kept getting in the way: herpes.

Dudley’s team noticed an unexpectedly high level of viral DNA from two human herpes viruses, HHV-6 and HHV-7. The viruses are common and cause a rash called roseola in young children (not the sexually transmitted disease caused by other strains).

Some viruses have the ability to lie dormant in our neurons for decades by incorporating their genomes into our own. The classic example is chickenpox: A childhood viral infection resolves and lurks silently, returning years later as shingles, an excruciating rash. Like it or not, nearly all of us are chimeras with viral DNA speckling our genomes.

But having the herpes viruses alone doesn’t mean inevitable brain decline. After all, up to 75 percent of us may harbor HHV-6 .

But Dudley also noticed that herpes appeared to interact with human genes known to increase Alzheimer’s risk. Perhaps, he says, there is some toxic combination of genetic and infectious influence that results in the disease; a combination that sparks what some feel is the main contributor to the disease, an overactive immune system.

The hallmark pathology of Alzheimer’s is accumulation of a protein called amyloid in the brain. Many researchers have assumed these aggregates, or plaques, are simply a byproduct of some other process at the core of the disease. Other scientists posit that the protein itself contributes to the condition in some way.

The theory that amyloid is the root cause of Alzheimer’s is losing steam. But the protein may still contribute to the disease, even if it winds up being deemed infectious.

Work by Harvard neuroscientist Rudolph Tanzi suggests it might be a bit of both. Along with colleague Robert Moir, Tanzi has shown that amyloid is lethal to viruses and bacteria in the test tube, and also in mice. He now believes the protein is part of our ancient immune system that like antibodies, ramps up its activity to help fend off unwanted bugs.

So does that mean that the microbe is the cause of Alzheimer’s, and amyloid a harmless reaction to it? According to Tanzi it’s not that simple.

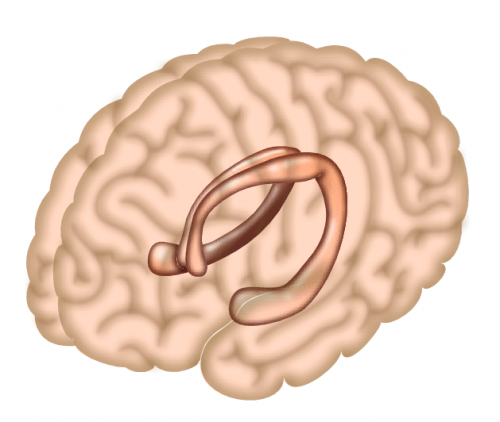

Tanzi believes that in many cases of Alzheimer’s, microbes are probably the initial seed that sets off a toxic tumble of molecular dominoes. Early in the disease amyloid protein builds up to fight infection, yet too much of the protein begins to impair function of neurons in the brain. The excess amyloid then causes another protein, called tau, to form tangles, which further harm brain cells.

But as Tanzi explains, the ultimate neurological insult in Alzheimer’s is the body’s reaction to this neurotoxic mess. All the excess protein revs up the immune system, causing inflammation — and it’s this inflammation that does the most damage to the Alzheimer’s-afflicted brain.

So what does this say about the future of treatment? Possibly a lot. Tanzi envisions a day when people are screened at, say, 50 years old. “If their brains are riddled with too much amyloid,” he says, “we knock it down a bit with antiviral medications. It’s just like how you are prescribed preventative drugs if your cholesterol is too high.”

Tanzi feels that microbes are just one possible seed for the complex pathology behind Alzheimer’s. Genetics may also play a role, as certain genes produce a type of amyloid more prone to clumping up. He also feels environmental factors like pollution might contribute.

Dr. James Burke, professor of medicine and psychiatry at Duke University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, isn’t willing to abandon the amyloid theory altogether, but agrees it’s time for the field to move on. “There may be many roads to developing Alzheimer’s disease and it would be shortsighted to focus just on amyloid and tau,” he says. “A million-dollar prize is attention- getting, but the reward for identifying a treatable target to delay or prevent Alzheimer’s disease is invaluable.”

Any treatment that disrupts the cascade leading to amyloid, tau and inflammation could theoretically benefit an at-risk brain. The vast majority of Alzheimer’s treatment trials have failed, including many targeting amyloid. But it could be that the patients included were too far along in their disease to reap any therapeutic benefit.

If a microbe is responsible for all or some cases of Alzheimer’s, perhaps future treatments or preventive approaches will prevent toxin protein buildup in the first place. Both Tanzi and Norins believe Alzheimer’s vaccines against viruses like herpes might one day become common practice.

In July of this year, in collaboration with Norins, the Infectious Diseases Society of America announced that they plan to offer two $50,000 grants supporting research into a microbial association with Alzheimer’s. According to Norins, this is the first acknowledgement by a leading infectious disease group that Alzheimer’s may be microbial in nature – or at least that it’s worth exploring.

“The important thing is not the amount of the money, which is a pittance compared with the $2 billion NIH spends on amyloid and tau research,” says Norins, “but rather the respectability and more mainstream status the grants confer on investigating of the infectious possibility. Remember when we thought ulcers were caused by stress?”

Ulcers, we now know, are caused by a germ.

https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/09/09/645629133/infectious-theory-of-alzheimers-disease-draws-fresh-interest?ft=nprml&f=1001