ey takeaways:

- Daily step counts between 5,000 to 10,000 or more reduced depression symptoms across 33 studies.

- The associations may be due to several mechanisms, like improvement in sleep quality and inflammation.

Daily step counts of 5,000 or more corresponded with fewer depressive symptoms among adults, results of a systematic review and meta-analysis published in JAMA Network Open suggested.

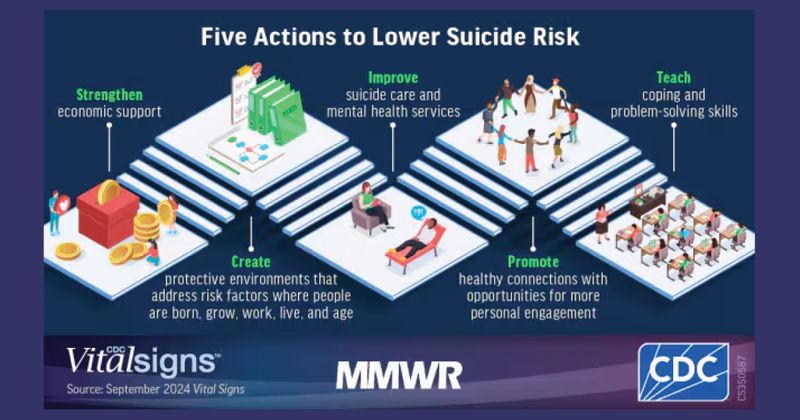

The results are consistent with previous studies linking exercise to various risk reductions for mental health disorders and show that setting step goals “may be a promising and inclusive public health strategy for the prevention of depression,” the researchers wrote.

According to Bruno Bizzozero-Peroni, PhD, MPH, from Universidad De Castilla-La Mancha in Spain, and colleagues, daily step counts are a “simple and intuitive objective measure” of physical activity, while tracking such counts has become increasingly feasible for the general population thanks to the availability of fitness trackers.

“To our knowledge, the association between the number of daily steps measured

with wearable trackers and depression has not been previously examined through a meta-analytic approach,” they wrote.

The researchers searched multiple databases for analyses assessing the effects of daily step counts on depressive symptoms, ultimately including a total of 27 cross-sectional studies and six longitudinal studies comprising 96,173 adults aged 18 years or older.

They found that in the cross-sectional studies, daily step counts of 10,000 or more (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.14), 7,500 to 9,999 (SMD = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.11) and 5,000 to 7,499 (SMD = 0.17; 95% CI, 0.3 to 0.04) corresponded with reduced depressive symptoms vs. daily step counts less than 5,000.

In the prospective cohort studies, people with 7,000 or more steps a day had a reduced risk for depression vs. with people with fewer than 7,000 daily steps (RR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.62-0.77), whereas an increase of 1,000 steps a day suggested an association with a lower risk for depression (RR = 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87-0.94).

There were a couple study limitations. The researchers noted that reverse associations are possible, while they could not rule out residual confounders.

They also pointed out that there are some remaining questions, such as whether there is a ceiling limit after which further step counts would no longer reduce the risk for depression.

Bizzozero-Peroni and colleagues highlighted several possible biological and psychosocial mechanisms behind the associations, like changes in sleep quality, inflammation, social support, self-esteem, neuroplasticity and self-efficacy.

They concluded that “a daily active lifestyle may be a crucial factor in regulating and reinforcing these pathways” regardless of the exact combination of mechanisms responsible for the positive link.

“Specifically designed experimental studies are still needed to explore whether there are optimal and maximal step counts for specific population subgroups,” they wrote.

Source:

Bizzozero-Peroni B, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.51208.