By Nicholas Weiler

UC San Francisco researchers have discovered a promising new line of attack against lethal, treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Analysis of hundreds of human prostate tumors revealed that the most aggressive cancers depend on a built-in cellular stress response to put a brake on their own hot-wired physiology. Experiments in mice and with human cells showed that blocking this stress response with an experimental drug — previously shown to enhance cognition and restore memory after brain damage in rodents — causes treatment-resistant cancer cells to self-destruct while leaving normal cells unaffected.

The new study was published online May 2, 2018 in Science Translational Medicine.

“We have learned that cancer cells become ‘addicted’ to protein synthesis to fuel their need for high-speed growth, but this dependence is also a liability: too much protein synthesis can become toxic,” said senior author Davide Ruggero, PhD, the Helen Diller Family Chair in Basic Cancer Research and a professor of urology and cellular and molecular pharmacology at UCSF. “We have discovered the molecular restraints that let cancer cells keep their addiction under control and showed that if we remove these restraints they quickly burn out under the pressure of their own greed for protein.”

“This is beautiful scientific work that could lead to urgently needed novel treatment strategies for men with very advanced prostate cancer,” added renowned UCSF Health prostate cancer surgeon Peter Carroll, MD, MPH, who is chair of the Department of Urology at UCSF and was a co-author on the new paper.

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death for men in the United States: More than one man in ten will be diagnosed in his lifetime, and one in forty-one will die of the disease, according to data from the American Cancer Society. Tumors that recur or fail to respond to surgery or radiation therapy are typically treated with hormonal therapies that target the cancer’s dependence on testosterone. Unfortunately, most cancers eventually develop resistance to hormone therapy, and become even more aggressive, leading to what is known as “castration-resistant” disease, which is nearly always fatal.

As part of a “growth first” strategy, many cancers contain gene mutations that drive them to produce proteins at such a high rate that they risk triggering cells’ built-in self-destruct mechanisms, according to studies previously conducted by Ruggero and colleagues. But aggressive, treatment-resistant prostate cancers typically contain multiple such mutations, which led Ruggero and his team at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center to wonder how such cancers sustain themselves under the pressure of so much protein production.

Deadliest Cancers Throttle Excess Protein Synthesis

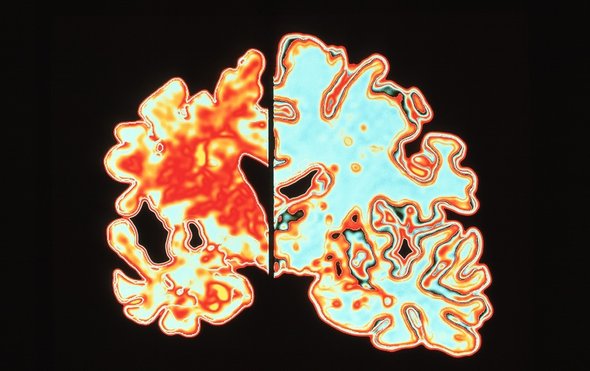

To explore this question, Ruggero’s team genetically engineered mice to develop prostate tumors containing a pair of mutations seen in nearly 50 percent of patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: one that causes overexpression of the cancer-driving MYC gene, and one that disables the tumor suppressor gene PTEN. They were surprised to discover that the highly aggressive cancers associated with these mutations actually had lower rates of protein synthesis compared to milder cancers with only a single mutation.

“I spent six months trying to understand if this was actually occurring, because it’s not at all what we expected,” said Crystal Conn, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher in the Ruggero lab and one of the paper’s two lead authors. But she saw the same effects again and again in experiments in mouse and human cancer cell lines as well as in 3-dimensional “organoid” models of the prostate that could be studied and manipulated in lab dishes.

Conn’s experiments eventually revealed that the combination of MYC and PTEN mutations trigger part of a cellular quality control system called the unfolded protein response (UPR), which reacts to cellular stress by reducing levels of protein synthesis throughout the cell. Specifically, these mutations alter the activity of a protein called eIF2a (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2a key regulator of protein synthesis, by turning it into an alternate form, P-eIF2a, which tunes down cellular protein production.

To assess whether levels of P-eIF2a in patient tumors could be used to predict the development of aggressive, treatment-resistant disease, Conn collaborated with Carroll, who holds the Ken and Donna Derr-Chevron Distinguished Professorship in Urology, and Hao Nguyen, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of urology, to examine 422 tumors surgically extracted from UCSF prostate cancer patients. They used a technique called tissue microarray to measure the levels of PTEN, Myc, and P-eIF2a proteins in these tumors, then asked how these biomarkers predicted patient outcomes using 10 years of clinical follow-up data.

They found that P-eIF2a levels were a powerful predictor of worse outcomes in patients with PTEN-mutant tumors: Only 4 percent of such tumors with low P-eIF2a continued to spread following surgery, while 19 percent of patients with high P-eIF2a went on to develop metastases, and many eventually died. In fact, the presence of PTEN mutations and high P-eIF2a levels in prostate tumors outperformed a current standard test (CAPRA-S) used to assess risk of cancer progression following surgery.

ISRIB Selectively Kills Aggressive Prostate Cancers

Next, the researchers examined whether blocking P-eIF2a‘s suppression of protein synthesis might effectively kill aggressive prostate cancers, said Nguyen, who was co–lead author on the new paper: “Once we realized that these cancers are activating part of the UPR to put the brakes on their own protein synthesis, we began to ask what happens to the cancer if you remove the brakes.”

The researchers collaborated with UCSF biochemist Peter Walter, PhD, whose lab recently identified a molecule called ISRIB that reverses the effects of P-eIF2a activity. (Walter and UCSF neuroscientist Susanna Rosi, PhD, have shown that ISRIB can boost cognition and restore memory after severe brain damage in rodents — likely by restoring the production of proteins needed for learning in injured brain cells.)

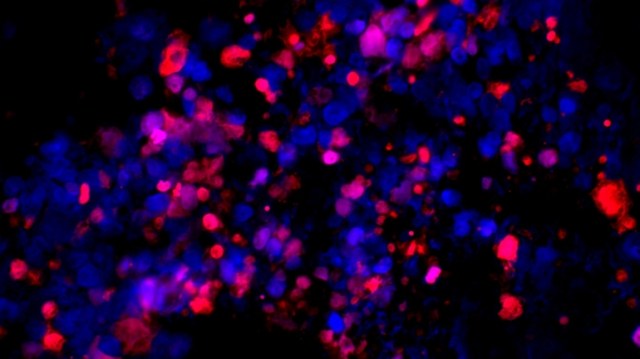

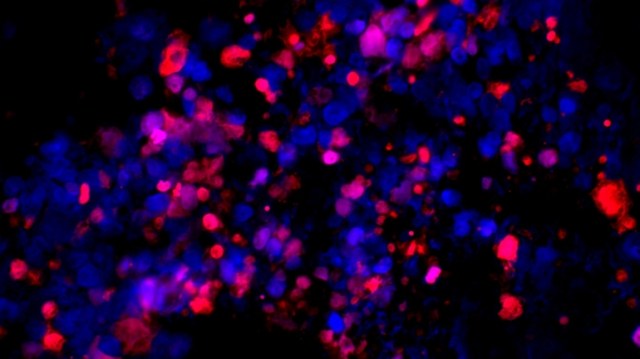

Conn tested ISRIB on mice with prostate tumors and in human cancer cell lines and discovered that the drug exposed aggressive cancer cells carrying combined PTEN/MYC mutations to their full drive for protein synthesis, causing them to self-destruct. Intriguingly, she found that the drug had little effect on normal tissue or even on less-aggressive cancers lacking the MYC mutation. In mice, PTEN/MYC prostate tumors began to shrink within 3 weeks of ISRIB treatment, and had not regrown after 6 weeks of treatment, while in contrast, PTEN-only tumors had expanded by 40 percent.

To further investigate the potential use of ISRIB against aggressive human prostate cancer, Nguyen implanted samples of human prostate cancer into mice, a research technique called “patient-derived xenografts” (PDX) that has historically been unsuccessful in studies of prostate cancer.

In one experiment, the researchers transplanted different groups of mice with cells from two tumors extracted from the same prostate cancer patient: one set of cells from the patient’s primary prostate tumor and another from a nearby metastatic colony in the patient’s lymph node. They found that mice implanted with cells from the metastatic sample — which exhibited the expected “aggressive” proteomic profile of high MYC, low PTEN, and high P-eIF2a levels — experienced dramatic tumor shrinkage and extended survival when treated with ISRIB, while mice implanted with cells from the less-aggressive primary prostate tumor experienced only a temporary slowing of tumor growth.

The authors used a third PDX model of metastatic prostate cancer to assess whether blocking the UPR could effectively treat advanced castration-resistant disease: they showed that transplanted tumors, which typically spread and kill mice within 10 days, were significantly reduced and the animals’ lives significantly extended under ISRIB treatment.

“Together these experiments show that blocking P-eIF2α signaling with ISRIB both slows down tumor progression and also kills off the cells that have already progressed or metastasized to become more aggressive,” Conn said. “This is very exciting because finding new treatments for castration-resistant prostate cancer is a pressing and unmet clinical need.”

The researchers hope that this discovery will quickly lead to clinical trials for ISRIB or related drugs for patients with advanced, aggressive prostate cancer. “Most molecules that kill cancer also kill normal cells,” Ruggero said. “But with ISRIB we’ve discovered a beautiful therapeutic window: normal cells are unaffected because they aren’t using this aspect of the UPR to control their protein synthesis but aggressive cancer cells are toast without it.”

“The only side effect we’re aware of,” Conn added, “is that this drug might make you smarter.”

Additional authors on the paper include: Yae Kye, Lingru Xue, Craig M Forester, MD, PhD, Janet E Cowan, Andrew C Hsieh, MD, John T Cunningham, PhD, Charles Truillet, PhD, Michael J Evans, PhD, Byron Hann, MD, PhD, and Peter Walter, PhD, of UCSF; Feven Tameire and Constantinos Koumenis, PhD, of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine; and Christopher P Evans, MD, and Joy C Yang, PhD, of the UC Davis School of Medicine.

The research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01-CA140456, R01-CA154916, and P01-CA165997), the US Department of Defense (W81XWH-15-1-0460), the AUA-SUO-Prostate Cancer Foundation (16YOUN14), the Urology Care Foundation (A130596), the American Cancer Society (PF-14-212-01-RMC), an American Association of Cancer Research (AACR)-Bayer Prostate Cancer Research Fellowship (17-40-44-CONN), the Campini Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Foundation, the American Cancer Society (130635-RSG-17-005-01-CCE), Calico Life Sciences LLC, the Weill Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), the UCSF Department of Pediatrics (5K12HDO72222-05), and the Goldberg-Benioff Program in Translational Cancer Biology.

https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2018/05/410336/research-finds-achilles-heel-aggressive-prostate-cancer