Aaron Elkins, a professor at the San Diego State University, is working on a kiosk system that can ask travelers questions at an airport or border crossings and capture behaviors to detect if someone is lying.

International travelers could find themselves in the near future talking to a lie-detecting kiosk when they’re going through customs at an airport or border crossing.

The same technology could be used to provide initial screening of refugees and asylum seekers at busy border crossings.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security funded research of the virtual border agent technology known as the Automated Virtual Agent for Truth Assessments in Real-Time, or AVATAR, about six years ago and allowed it to be tested it at the U.S.-Mexico border on travelers who volunteered to participate. Since then, Canada and the European Union tested the robot-like kiosk that uses a virtual agent to ask travelers a series of questions.

Last month, a caravan of migrants from Central America made it to the U.S.-Mexico border, where they sought asylum but were delayed several days because the port of entry near San Diego had reached full capacity. It’s possible that a system such as AVATAR could provide initial screening of asylum seekers and others to help U.S. agents at busy border crossings such as San Diego’s San Ysidro.

“The technology has much broader applications potentially,” despite most of the funding for the original work coming primarily from the Defense or Homeland Security departments a decade ago, according to Aaron Elkins, one of the developers of the system and an assistant professor at the San Diego State University director of its Artificial Intelligence Lab. He added that AVATAR is not a commercial product yet but could be also used in human resources for screening.

The U.S.-Mexico border trials with the advanced kiosk took place in Nogales, Arizona, and focused on low-risk travelers. The research team behind the system issued a report after the 2011-12 trials that stated the AVATAR technology had potential uses for processing applications for citizenship, asylum and refugee status and to reduce backlogs.

High levels of accuracy

President Donald Trump’s fiscal 2019 budget request for Homeland Security includes $223 million for “high-priority infrastructure, border security technology improvements,” as well as another $210.5 million for hiring new border agents. Last year, federal workers interviewed or screened more than 46,000 refugee applicants and processed nearly 80,000 “credible fear cases.”

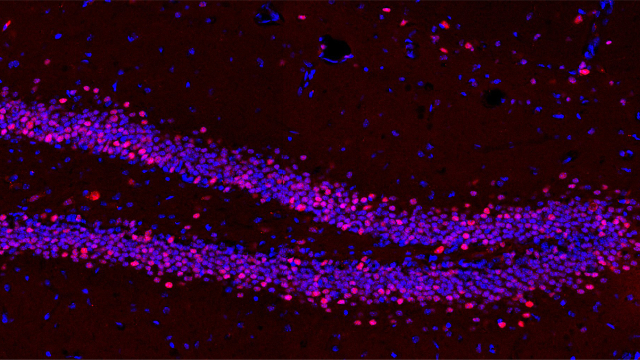

The AVATAR combines artificial intelligence with various sensors and biometrics that seeks to flag individuals who are untruthful or a potential risk based on eye movements or changes in voice, posture and facial gestures.

“We’re always consistently above human accuracy,” said Elkins, who worked on the technology with a team of researchers that included the University of Arizona.

According to Elkins, the AVATAR as a deception-detection judge has a success rate of 60 to 75 percent and sometimes up to 80 percent.

“Generally, the accuracy of humans as judges is about 54 to 60 percent at the most,” he said. “And that’s at our best days. We’re not consistent.”

The human element

Regardless, Homeland Security appears to be sticking with human agents for the moment and not embracing virtual technology that the EU and Canadian border agencies are still researching. Another advanced border technology, known as iBorderCtrl, is a EU-funded project that aims to increase speed but also reduce “the workload and subjective errors caused by human agents.”

A Homeland Security official, who declined to be named, told CNBC the concept for the AVATAR system “was envisioned by researchers to assist human screeners by flagging people exhibiting suspicious or anomalous behavior.”

“As the research effort matured, the system was evaluated and tested by the DHS Science and Technology Directorate and DHS operational components in 2012,” the official added. “Although the concept was appealing at the time, the research did not mature enough for further consideration or further development.”

Another DHS official familiar with the technology didn’t work at a high enough rate of speed to be practical. “We have to screen people within seconds, and we can’t take minutes to do it,” said the official.

Elkins, meanwhile, said the funding for the AVATAR system hasn’t come from Homeland Security in recent years “because they sort of felt that this is in a different category now and needs to transition.”

The technology, which relies on advanced statistics and machine learning, was tested a year and a half ago with the Canadian Border Services Agency, or CBSA, to help agents determine whether a traveler has ulterior motives entering the country and should be questioned further or denied entry.

A report from the CBSA on the AVATAR technology is said to be imminent, but it’s unclear whether the agency will proceed the technology beyond the testing phase.

“The CBSA has been following developments in AVATAR technology since 2011 and is continuing to monitor developments in this field,” said Barre Campbell, a senior spokesman for the Canadian agency. He said the work carried out in March 2016 was “an internal-only experiment of AVATAR” and that “analysis for this technology is ongoing.”

Prior to that, the EU border agency known as Frontex helped coordinate and sponsor a field test of the AVATAR system in 2014 at the international arrivals section of an airport in Bucharest, Romania.

People and machines working together

Once the system detects deception, it alerts the human agents to do follow-up interviews.

AVATAR doesn’t use your standard polygraph instrument. Instead, people face a kiosk screen and talk to a virtual agent or kiosk fitted with various sensors and biometrics that seeks to flag individuals who are untruthful or signal a potential risk based on eye movements or changes in voice, posture and facial gestures.

“Artificial intelligence has allowed us to use sensors that are noncontact that we can then process the signal in really advanced ways,” Elkins said. “We’re able to teach computers to learn from some data and actually act intelligently. The science is very mature over the last five or six years.”

But the researcher insists the AVATAR technology wasn’t developed as a replacement for people.

“We wanted to let people focus on what they do best,” he said. “Let the systems do what they do best and kind of try to merge them into the process.”

Still, future advancement in artificial intelligence systems may allow the technology to someday supplant various human jobs because the robot-like machines may be seen as more productive and cost effective particularly in screening people.

Elkins believes the AVATAR could potentially get used one day at security checkpoints at airports “to make the screening process faster but also to improve the accuracy.”

“It’s just a matter of finding the right implementation of where it will be and how it will be used,” he said. “There’s also a process that would need to occur because you can’t just drop the AVATAR into an airport as it exists now because all that would be using an extra step.”

Thanks to Kebmodee for bringing this to the It’s Interesting community.