The Standard Model. What dull name for the most accurate scientific theory known to human beings.

More than a quarter of the Nobel Prizes in physics of the last century are direct inputs to or direct results of the Standard Model. Yet its name suggests that if you can afford a few extra dollars a month you should buy the upgrade. As a theoretical physicist, I’d prefer The Absolutely Amazing Theory of Almost Everything. That’s what the Standard Model really is.

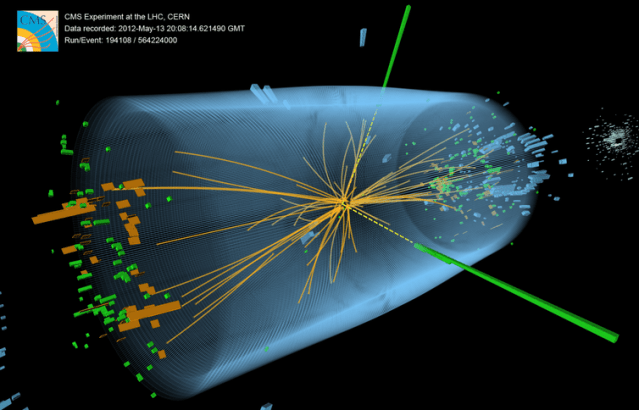

Many recall the excitement among scientists and media over the 2012 discovery of the Higgs boson. But that much-ballyhooed event didn’t come out of the blue – it capped a five-decade undefeated streak for the Standard Model. Every fundamental force but gravity is included in it. Every attempt to overturn it to demonstrate in the laboratory that it must be substantially reworked – and there have been many over the past 50 years – has failed.

In short, the Standard Model answers this question: What is everything made of, and how does it hold together?

The smallest building blocks

You know, of course, that the world around us is made of molecules, and molecules are made of atoms. Chemist Dmitri Mendeleev figured that out in the 1860s and organized all atoms – that is, the elements – into the periodic table that you probably studied in middle school. But there are 118 different chemical elements. There’s antimony, arsenic, aluminum, selenium … and 114 more.

But these elements can be broken down further.

Physicists like things simple. We want to boil things down to their essence, a few basic building blocks. Over a hundred chemical elements is not simple. The ancients believed that everything is made of just five elements – earth, water, fire, air and aether. Five is much simpler than 118. It’s also wrong.

By 1932, scientists knew that all those atoms are made of just three particles – neutrons, protons and electrons. The neutrons and protons are bound together tightly into the nucleus. The electrons, thousands of times lighter, whirl around the nucleus at speeds approaching that of light. Physicists Planck, Bohr, Schroedinger, Heisenberg and friends had invented a new science – quantum mechanics – to explain this motion.

That would have been a satisfying place to stop. Just three particles. Three is even simpler than five. But held together how? The negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons are bound together by electromagnetism. But the protons are all huddled together in the nucleus and their positive charges should be pushing them powerfully apart. The neutral neutrons can’t help.

What binds these protons and neutrons together? “Divine intervention” a man on a Toronto street corner told me; he had a pamphlet, I could read all about it. But this scenario seemed like a lot of trouble even for a divine being – keeping tabs on every single one of the universe’s 10⁸⁰ protons and neutrons and bending them to its will.

Expanding the zoo of particles

Meanwhile, nature cruelly declined to keep its zoo of particles to just three. Really four, because we should count the photon, the particle of light that Einstein described. Four grew to five when Anderson measured electrons with positive charge – positrons – striking the Earth from outer space. At least Dirac had predicted these first anti-matter particles. Five became six when the pion, which Yukawa predicted would hold the nucleus together, was found.

Then came the muon – 200 times heavier than the electron, but otherwise a twin. “Who ordered that?” I.I. Rabi quipped. That sums it up. Number seven. Not only not simple, redundant.

By the 1960s there were hundreds of “fundamental” particles. In place of the well-organized periodic table, there were just long lists of baryons (heavy particles like protons and neutrons), mesons (like Yukawa’s pions) and leptons (light particles like the electron, and the elusive neutrinos) – with no organization and no guiding principles.

Into this breach sidled the Standard Model. It was not an overnight flash of brilliance. No Archimedes leapt out of a bathtub shouting “eureka.” Instead, there was a series of crucial insights by a few key individuals in the mid-1960s that transformed this quagmire into a simple theory, and then five decades of experimental verification and theoretical elaboration.

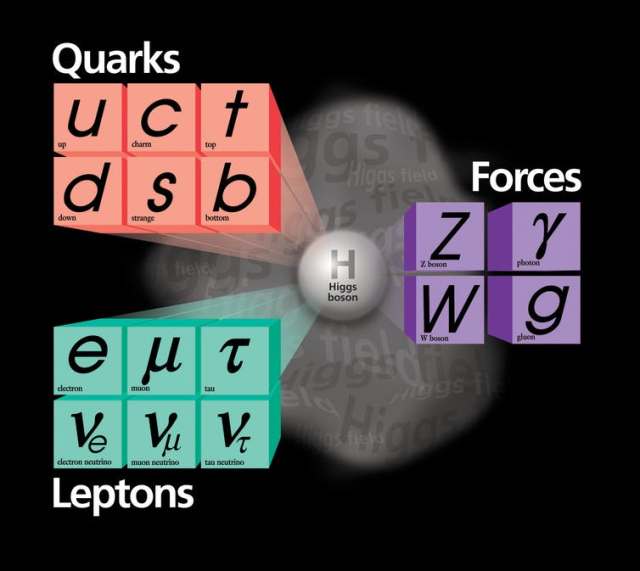

Quarks. They come in six varieties we call flavors. Like ice cream, except not as tasty. Instead of vanilla, chocolate and so on, we have up, down, strange, charm, bottom and top. In 1964, Gell-Mann and Zweig taught us the recipes: Mix and match any three quarks to get a baryon. Protons are two ups and a down quark bound together; neutrons are two downs and an up. Choose one quark and one antiquark to get a meson. A pion is an up or a down quark bound to an anti-up or an anti-down. All the material of our daily lives is made of just up and down quarks and anti-quarks and electrons.

The Standard Model of elementary particles provides an ingredients list for everything around us.

Simple. Well, simple-ish, because keeping those quarks bound is a feat. They are tied to one another so tightly that you never ever find a quark or anti-quark on its own. The theory of that binding, and the particles called gluons (chuckle) that are responsible, is called quantum chromodynamics. It’s a vital piece of the Standard Model, but mathematically difficult, even posing an unsolved problem of basic mathematics. We physicists do our best to calculate with it, but we’re still learning how.

The other aspect of the Standard Model is “A Model of Leptons.” That’s the name of the landmark 1967 paper by Steven Weinberg that pulled together quantum mechanics with the vital pieces of knowledge of how particles interact and organized the two into a single theory. It incorporated the familiar electromagnetism, joined it with what physicists called “the weak force” that causes certain radioactive decays, and explained that they were different aspects of the same force. It incorporated the Higgs mechanism for giving mass to fundamental particles.

Since then, the Standard Model has predicted the results of experiment after experiment, including the discovery of several varieties of quarks and of the W and Z bosons – heavy particles that are for weak interactions what the photon is for electromagnetism. The possibility that neutrinos aren’t massless was overlooked in the 1960s, but slipped easily into the Standard Model in the 1990s, a few decades late to the party.

Discovering the Higgs boson in 2012, long predicted by the Standard Model and long sought after, was a thrill but not a surprise. It was yet another crucial victory for the Standard Model over the dark forces that particle physicists have repeatedly warned loomed over the horizon. Concerned that the Standard Model didn’t adequately embody their expectations of simplicity, worried about its mathematical self-consistency, or looking ahead to the eventual necessity to bring the force of gravity into the fold, physicists have made numerous proposals for theories beyond the Standard Model. These bear exciting names like Grand Unified Theories, Supersymmetry, Technicolor, and String Theory.

Sadly, at least for their proponents, beyond-the-Standard-Model theories have not yet successfully predicted any new experimental phenomenon or any experimental discrepancy with the Standard Model.

After five decades, far from requiring an upgrade, the Standard Model is worthy of celebration as the Absolutely Amazing Theory of Almost Everything.