Most people have a moral compass, or intuition for right and wrong, even if they don’t always follow it. This inner voice has long been credited to culture and religion, but while society does influence our sense of ethics, the roots of morality also seem to run much deeper. Research suggests it’s an ancient instinct in humans, and has found hints of morality in some other social animals, too.

And despite the wide variety of human cultures around the world, a new study identifies seven “universal moral rules” that exist in virtually every society. The study, published this month in the journal Current Anthropology, is “the largest and most comprehensive cross-cultural survey of morals ever conducted,” according to a news release about the findings from the University of Oxford.

“The debate between moral universalists and moral relativists has raged for centuries, but now we have some answers,” says lead author Oliver Scott Curry, senior researcher at Oxford’s Institute for Cognitive and Evolutionary Anthropology, in a statement. “People everywhere face a similar set of social problems, and use a similar set of moral rules to solve them.”

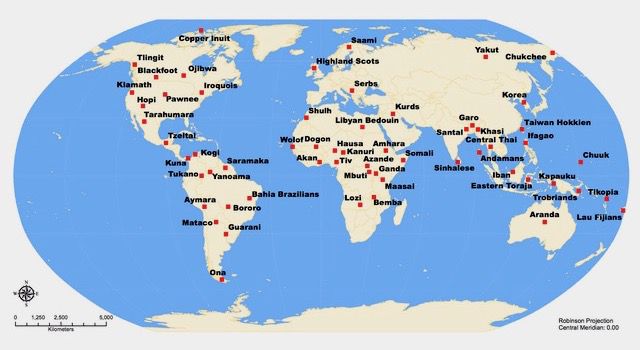

Earlier studies have looked at some of these rules in certain places, Curry and his colleagues note, but none have analyzed all of them across a broad, representative sample of societies. For this new study, they explored a database called the Human Relations Area Files, which includes thousands of ethnographies “from simple hunter-gatherer bands to kingdoms and modern states.” They examined ethnographic views of morality from a stratified random sample of 60 societies around the planet (see map below), comprising more than 600,000 words from more than 600 sources.

They found that seven forms of cooperative behavior “are always seen as morally good,” with not a single society viewing any of them as morally bad. The morals seem to exist with equal frequency across continents, the researchers report, noting they are “not the exclusive preserve of ‘the West’ or any other region.”

Here is a list of those seven guidelines, which the study’s authors describe as “plausible candidates for universal moral rules”:

Help your family.

Help your group.

Return favors.

Be brave.

Defer to superiors.

Divide resources fairly.

Respect others’ property.

The study tests the theory of morality as cooperation, its authors write, which argues morality is “a collection of biological and cultural solutions to the problems of cooperation recurrent in human social life.” It’s part of the idea that morality evolved in social animals because it unifies and bolsters their groups, discouraging individuals from behaving selfishly at the expense of the greater good.

Since there are many types of cooperation, this theory suggests we’ve adapted by developing many types of morality. We may be willing to risk our own lives to protect close relatives, for example, due to the evolutionary benefits of kin selection. We value unity, solidarity and loyalty because there’s strength and safety in numbers, compelling us to form groups and coalitions. Social exchange can explain why we build trust and return favors, as well as our patterns of guilt, gratitude, atonement and forgiveness. The need for conflict resolution may drive us to admire both “hawkish displays of dominance” (bravery) and “dovish displays of submission” (deference to superiors), along with fair division of resources and property rights.

“Everyone everywhere shares a common moral code,” Curry says. “All agree that cooperating, promoting the common good, is the right thing to do.”

Every society seems to agree on these seven basic rules, but the study did find variations in how the rules are prioritized. That makes sense, since their ambiguity could set the stage for moral dilemmas. If your family betrays your country, for example, which loyalty takes precedence? And how much should we really defer to corrupt superiors who abuse their power? “In some societies, family appeared to trump group; in other societies it was the other way around,” the researchers write. “In some societies there was an overwhelming obligation to seek revenge; in other societies this was trumped by the desire to maintain group solidarity.”

It’s worth noting these rules focus widely on what we should do, without specifying particular sins to avoid. They are broad principles, illuminating our shared values but not necessarily offering a definitive code of human ethics. Their ambiguity means they could encompass specific taboos that aren’t spelled out, but the authors add that under the theory of morality as cooperation, “behavior not tied to a specific type of cooperation will not constitute a distinct moral domain.”

Hitting someone without permission, for example, “is not a foundational moral violation,” they write. “Instead, the moral valence of harm will vary according to the cooperative context: uncooperative harm (battery) will be considered morally bad, but cooperative harm (punishment, self-defense) will be considered morally good, and competitive harm in zero-sum contexts (some aspects of mate competition and intergroup conflict) will be considered morally neutral — ‘all’s fair in love and war.'”

A growing body of research suggests altruistic instincts push humans and other social animals to cooperate, but some researchers say the “morality as cooperation” theory is still too reductive. It may not account for societies in which cooperative traits aren’t considered moral, for example, like utilitarians who don’t care about kinship or anarchists who don’t defer to superiors. Cooperation may also fail to explain certain aspects of human ethics like sexual morality, as some outside researchers write in comments published along with the new study, or the existence of destructive morals throughout human history. Massimo Pigliucci, a professor of philosophy at City College of New York, has also called the study’s premise “both interesting and more than a bit irritating,” arguing that it “fails to make the crucial conceptual distinction between the origins of morality and its current function.”

Curry and his colleagues address many of these points in a reply at the end of their paper. They found no societies where these seven rules don’t fit, even though “our survey methodology explicitly set out to find them,” they write, arguing that any such society would be an “outlier” whose beliefs don’t represent humanity as a whole. Still, they agree it remains to be seen whether morality as cooperation “can explain all moral phenomena,” and that sexual morality in particular is still poorly understood. They also acknowledge that “morals sometimes go wrong,” but say those cases could just reflect “the inevitable limitations and by-products of cooperative strategies.”

Morality may be instinctive, but even after all this time, we still have a lot to learn about it. More research will be needed to test this and other theories about our ethical instincts, the authors of the new study write, but for now they hope there’s at least one clear moral to this story: “We hope that this research helps to promote mutual understanding between people of different cultures, an appreciation of what we have in common, and how and why we differ,” Curry says.

https://www.mnn.com/lifestyle/responsible-living/blogs/universal-moral-rules?utm_source=Weekly+Newsletter&utm_campaign=dc5ab96a6c-RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_WED0227_2019&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_fcbff2e256-dc5ab96a6c-40844241