by Antonio Regalado

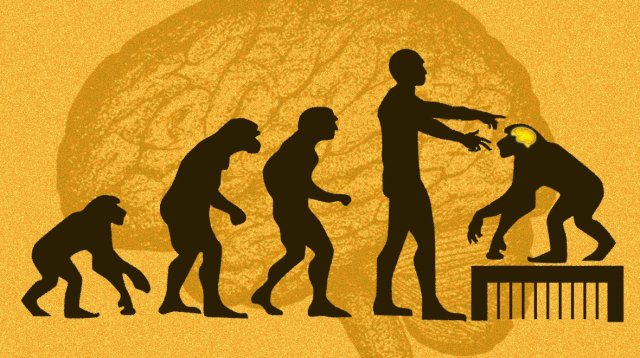

Human intelligence is one of evolution’s most consequential inventions. It is the result of a sprint that started millions of years ago, leading to ever bigger brains and new abilities. Eventually, humans stood upright, took up the plow, and created civilization, while our primate cousins stayed in the trees.

Now scientists in southern China report that they’ve tried to narrow the evolutionary gap, creating several transgenic macaque monkeys with extra copies of a human gene suspected of playing a role in shaping human intelligence.

“This was the first attempt to understand the evolution of human cognition using a transgenic monkey model,” says Bing Su, the geneticist at the Kunming Institute of Zoology who led the effort.

According to their findings, the modified monkeys did better on a memory test involving colors and block pictures, and their brains also took longer to develop—as those of human children do. There wasn’t a difference in brain size.

The experiments, described on March 27 in a Beijing journal, National Science Review, and first reported by Chinese media, remain far from pinpointing the secrets of the human mind or leading to an uprising of brainy primates.

Instead, several Western scientists, including one who collaborated on the effort, called the experiments reckless and said they questioned the ethics of genetically modifying primates, an area where China has seized a technological edge.

“The use of transgenic monkeys to study human genes linked to brain evolution is a very risky road to take,” says James Sikela, a geneticist who carries out comparative studies among primates at the University of Colorado. He is concerned that the experiment shows disregard for the animals and will soon lead to more extreme modifications. “It is a classic slippery slope issue and one that we can expect to recur as this type of research is pursued,” he says.

Research using primates is increasingly difficult in Europe and the US, but China has rushed to apply the latest high-tech DNA tools to the animals. The country was first to create monkeys altered with the gene-editing tool CRISPR, and this January a Chinese institute announced it had produced a half-dozen clones of a monkey with a severe mental disturbance.

“It is troubling that the field is steamrolling along in this manner,” says Sikela.

Evolution story

Su, a researcher at the Kunming Institute of Zoology, specializes in searching for signs of “Darwinian selection”—that is, genes that have been spreading because they’re successful. His quest has spanned such topics as Himalayan yaks’ adaptation to high altitude and the evolution of human skin color in response to cold winters.

The biggest riddle of all, though, is intelligence. What we know is that our humanlike ancestors’ brains rapidly grew in size and power. To find the genes that caused the change, scientists have sought out differences between humans and chimpanzees, whose genes are about 98% similar to ours. The objective, says, Sikela, was to locate “the jewels of our genome”—that is, the DNA that makes us uniquely human.

For instance, one popular candidate gene called FOXP2—the “language gene” in press reports—became famous for its potential link to human speech. (A British family whose members inherited an abnormal version had trouble speaking.) Scientists from Tokyo to Berlin were soon mutating the gene in mice and listening with ultrasonic microphones to see if their squeaks changed.

Su was fascinated by a different gene, MCPH1, or microcephalin. Not only did the gene’s sequence differ between humans and apes, but babies with damage to microcephalin are born with tiny heads, providing a link to brain size. With his students, Su once used calipers and head spanners to the measure the heads of 867 Chinese men and women to see if the results could be explained by differences in the gene.

By 2010, though, Su saw a chance to carry out a potentially more definitive experiment—adding the human microcephalin gene to a monkey. China by then had begun pairing its sizeable breeding facilities for monkeys (the country exports more than 30,000 a year) with the newest genetic tools, an effort that has turned it into a mecca for foreign scientists who need monkeys to experiment on.

To create the animals, Su and collaborators at the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research exposed monkey embryos to a virus carrying the human version of microcephalin. They generated 11 monkeys, five of which survived to take part in a battery of brain measurements. Those monkeys each have between two and nine copies of the human gene in their bodies.

Su’s monkeys raise some unusual questions about animal rights. In 2010, Sikela and three colleagues wrote a paper called “The ethics of using transgenic non-human primates to study what makes us human,” in which they concluded that human brain genes should never be added to apes, such as chimpanzees, because they are too similar to us. “You just go to the Planet of the Apes immediately in the popular imagination,” says Jacqueline Glover, a University of Colorado bioethicist who was one of the authors. “To humanize them is to cause harm. Where would they live and what would they do? Do not create a being that can’t have a meaningful life in any context.”

In an e-mail, Su says he agrees that apes are so close to humans that their brains shouldn’t be changed. But monkeys and humans last shared an ancestor 25 million years ago. To Su, that alleviates the ethical concerns. “Although their genome is close to ours, there are also tens of millions of differences,” he says. He doesn’t think the monkeys will become anything more than monkeys. “Impossible by introducing only a few human genes,” he says.

Smart monkey?

Judging by their experiments, the Chinese team did expect that their transgenic monkeys could end up with increased intelligence and brain size. That is why they put the creatures inside MRI machines to measure their white matter and gave them computerized memory tests. According to their report, the transgenic monkeys didn’t have larger brains, but they did better on a short-term memory quiz, a finding the team considers remarkable.

Several scientists think the Chinese experiment didn’t yield much new information. One of them is Martin Styner, a University of North Carolina computer scientist and specialist in MRI who is listed among the coauthors of the Chinese report. Styner says his role was limited to training Chinese students to extract brain volume data from MRI images, and that he considered removing his name from the paper, which he says was not able to find a publisher in the West.

“There are a bunch of aspects of this study that you could not do in the US,” says Styner. “It raised issues about the type of research and whether the animals were properly cared for.”

After what he’s seen, Styner says he’s not looking forward to more evolution research on transgenic monkeys. “I don’t think that is a good direction,” he says. “Now we have created this animal which is different than it is supposed to be. When we do experiments, we have to have a good understanding of what we are trying to learn, to help society, and that is not the case here.” One issue is that genetically modified monkeys are expensive to create and care for. With just five modified monkeys, it’s hard to reach firm conclusions about whether they really differ from normal monkeys in terms of brain size or memory skills. “They are trying to understand brain development. And I don’t think they are getting there,” says Styner.

In an e-mail, Su agreed that the small number of animals was a limitation. He says he has a solution, though. He is making more of the monkeys and is also testing new brain evolution genes. One that he has his eye on is SRGAP2C, a DNA variant that arose about two million years ago, just when Australopithecus was ceding the African savannah to early humans. That gene has been dubbed the “humanity switch” and the “missing genetic link” for its likely role in the emergence of human intelligence.

Su says he’s been adding it to monkeys, but that it’s too soon to say what the results are.