By Simon Makin

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval last month of a depression treatment based on ketamine generated headlines, in part, because the drug represents a completely new approach for dealing with a condition the World Health Organisation has labelled the leading cause of disability worldwide. The FDA’s approval marks the first genuinely new type of psychiatric drug—for any condition—to be brought to market in more than 30 years.

Although better known as a party drug, the anesthetic ketamine has spurred excitement in psychiatry for almost 20 years, since researchers first showed that it alleviated depression in a matter of hours. The rapid reversal of symptoms contrasted sharply with the existing set of antidepressants, which take weeks to begin working. Subsequent studies have shown ketamine works for patients who have failed to respond to multiple other treatments, and so are deemed “treatment-resistant.”

Despite this excitement, researchers still don’t know exactly how ketamine exerts its effects. A leading theory proposes that it stimulates regrowth of synapses (connections between neurons), effectively rewiring the brain. Researchers have seen these effects in animals’ brains, but the exact details and timing are elusive.

A new study, from a team led by neuroscientist and psychiatrist Conor Liston at Weill Cornell Medicine, has confirmed that synapse growth is involved, but not in the way many researchers were expecting. Using cutting-edge technology to visualize and manipulate the brains of stressed mice, the study reveals how ketamine first induces changes in brain circuit function, improving “depressed” mice’s behavior within three hours, and only later stimulating regrowth of synapses.

As well as shedding new light on the biology underlying depression, the work suggests new avenues for exploring how to sustain antidepressant effects over the long term. “It’s a remarkable engineering feat, where they were able to visualize changes in neural circuits over time, corresponding with behavioral effects of ketamine,” says Carlos Zarate, chief of the Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch at the National Institute of Mental Health, who was not involved in the study. “This work will likely set a path for what treatments should be doing before we move them into the clinic.”

Another reason ketamine has researchers excited is that it works differently than existing antidepressants. Rather than affecting one of the “monoamine” neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine), as standard antidepressants do, it acts on glutamate, the most common chemical messenger in the brain. Glutamate plays an important role in the changes synapses undergo in response to experiences that underlie learning and memory. That is why researchers suspected such “neuroplasticity” would lie at the heart of ketamine’s antidepressant effects.

Ketamine’s main drawback is its side effects, which include out-of-body experiences, addiction and bladder problems. It is also not a “cure.” The majority of recipients who have severe, difficult-to-treat depression will ultimately relapse. A course of multiple doses typically wears off within a few weeks to months. Little is known about the biology underlying depressive states, remission and relapse. “A big question in the field concerns the mechanisms that mediate transitions between depression states over time,” Liston says. “We were trying to get a better handle on that in the hopes we might be able to figure out better ways of preventing depression and sustaining recovery.”

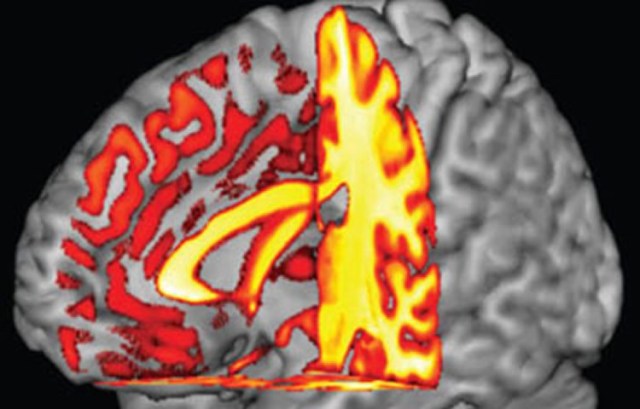

Chronic stress depletes synapses in certain brain regions, notably the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), an area implicated in multiple aspects of depression. Mice subjected to stress display depressionlike behaviors, and with antidepressant treatment, they often improve. In the new study, the researchers used light microscopes to observe tiny structures called spines located on dendrites (a neuron’s “input” wires) in the mPFC of stressed mice. Spines play a key role because they form synapses if they survive for more than a few days.

For the experiment, some mice became stressed when repeatedly restrained, others became so after they were administered the stress hormone corticosterone. “That’s a strength of this study,” says neuroscientist Anna Beyeler, of the University of Bordeaux, France, who was not involved in the work, but wrote an accompanying commentary article in Science. “If you’re able to observe the same effects in two different models, this really strengthens the findings.” The team first observed the effects of subjecting mice to stress for 21 days, confirming that this resulted in lost spines. The losses were not random, but clustered on certain dendrite branches, suggesting the damage targets specific brain circuits.

The researchers then looked a day after administering ketamine and found that the number of spines increased. Just over half appeared in the same location as spines that were previously lost, suggesting a partial reversal of stress-induced damage. Depressionlike behaviors caused by the stress also improved. The team measured brain circuit function in the mPFC, also impaired by stress, by calculating the degree to which activity in cells was coordinated, a measure researchers term “functional connectivity.” This too improved with ketamine.

When the team looked closely at the timing of all this, they found that improvements in behavior and circuit function both occurred within three hours, but new spines were not seen until 12 to 24 hours after treatment. This suggests that the formation of new synapses is a consequence, rather than cause, of improved circuit function. Yet they also saw that mice who regrew more spines after treatment performed better two to seven days later. “These findings suggest that increased ensemble activity contributes to the rapid effects of ketamine, while increased spine formation contributes to the sustained antidepressant actions of ketamine,” says neuroscientist Ronald Duman, of the Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. Although the molecular details of what happens in the first hours are not yet fully understood, it seems a restoration of coordinated circuit activity occurs first; this is then entrenched by neuroplasticity effects in synapses, which then maintain behavioral benefits over time.

To prove that new synapses were a cause of antidepressant effects, rather than just coinciding with the improved behaviors, the team used a newly developed optogenetic technique, which allowed them to eliminate newly formed spines using light. Optogenetics works by introducing viruses that genetically target cells, causing them to produce light-sensitive proteins. In this case, the protein is expressed in newly formed synapses, and exposure to blue light causes the synapse to collapse. The researchers found that eliminating newly formed synapses in ketamine-treated mice abolished some of the drug’s positive effects, two days after treatment, confirming that new synapses are needed to maintain benefits. “Many mechanisms are surely involved in determining why some people relapse and some don’t,” Liston says, ” but we think our work shows that one of those involves the durability of these new synapses that form.”

And Liston adds: “Our findings open up new avenues for research, suggesting that interventions aimed at enhancing the survival of these new synapses might be useful for extending ketamine’s antidepressant effects.” The implication is that targeting newly formed spines might be useful for maintaining remission after ketamine treatment. “This is a great question and one the field has been considering,” Duman says. “This could include other drugs that target stabilization of spines, or behavioral therapies designed to engage the new synapses and circuits, thereby strengthening them.”

The study used three behavioral tests: one involving exploration, a second a struggle to escape, and a third an assessment of how keen the mice are on a sugar solution. This last test is designed to measure anhedonia—a symptom of depression in which the ability to experience pleasure is lost. This test was unaffected by deleting newly formed spines, suggesting that the formation of new synapses in the mPFC is important for some symptoms, such as apathy, but not others (anhedonia)—and that different aspects of depression involve a variety of brain circuits.

These results could relate to a study published last year that found activity in another brain region, the lateral habenula, is crucially involved in anhedonia, and injecting ketamine directly into this region improves anhedonia-related behavior in mice. “We’re slowly identifying specific regions associated with specific behaviors,” Beyeler says. “The factors leading to depression might be different depending on the individual, so these different models might provide information regarding the causes of depression.”

One caveat is that the study looked at only a single dose, rather than the multiple doses involved in a course of human treatment, Zarate says. After weeks of repeated treatments, might the spines remain, despite a relapse, or might they dwindle, despite the mice still doing well? “Ongoing effects with repeated administration, we don’t know,” Zarate says. “Some of that work will start taking off now, and we’ll learn a lot more.” Of course, the main caution is that stressed mice are quite far from humans with depression. “There’s no real way to measure synaptic plasticity in people, so it’s going to be hard to confirm these findings in humans,” Beyeler says.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/behind-the-buzz-how-ketamine-changes-the-depressed-patients-brain/