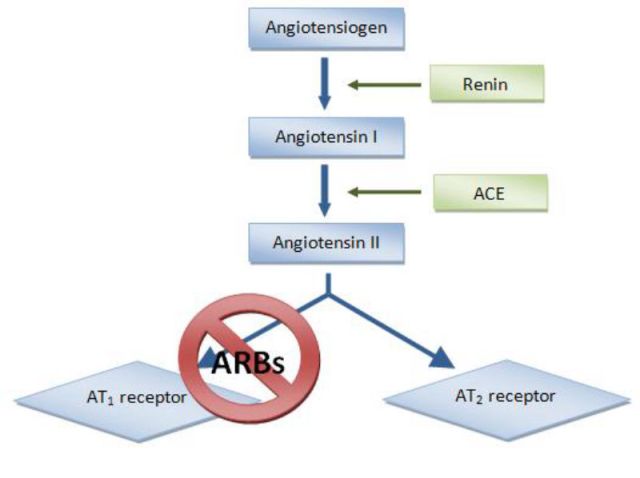

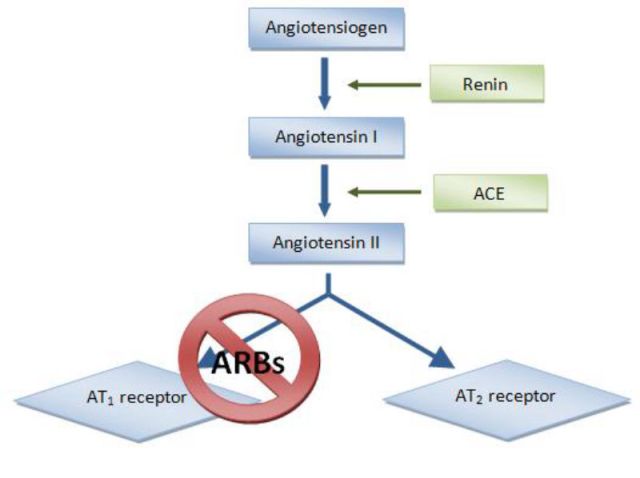

The antihypertension drugs called ARBs disrupt the pathway that leads to blood vessel constriction by preventing angiotensin II from binding to the AT1 receptor. This now-available angiotensin is then processed by ACE2 (not shown) into the form that leads to blood vessel dilation. ACE inhibitors work by blocking the production of angiotensin II.

A coronavirus spike protein (red) binds to an ACE2 receptor (blue).

For the past few weeks, research journals have been publishing reports on the connection between medications that reduce high blood pressure and COVID-19. The concern is that the medications might increase the abundance of the receptor that SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—uses to enter cells. Boosting levels of these ACE2 receptors on lung and heart cells could give the virus more cellular entry points to target and potentially make symptoms of the disease more severe.

It’s a hypothesis that is important to test, notes Carlos Ferrario, a professor of general surgery at Wake Forest School of Medicine who specializes in research on antihypertensive drugs.

So far, the data supporting the connection between blood pressure medications—specifically, angiotensin-converting-enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)—and COVID-19 are scant. Yet media coverage of the connection has led patients prescribed the drugs to call their doctors asking if they should stop taking them. In response, several medical associations—including the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the European Society of Cardiology—have issued guidelines saying patients should not stop taking the antihypertensive drugs because there’s no evidence to support the claim that they cause more-severe SARS-CoV-2 infections.

In support of that recommendation, Ankit Patel, a clinical and research fellow focusing on the kidneys at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his Brigham colleague Ashish Verma dug into the literature to address the confusion and reported March 24 in JAMA that there’s no definitive evidence to suggest ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase the severity of COVID-19. Another team of doctors, writing in the March 30 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, came to the same conclusion.

Instead of making COVID-19 symptoms worse, some antihypertensive drugs may actually reduce the severity of infections, and could therefore be used to treat the disease, both sets of doctors say. A closer look at the underlying mechanisms of the medications has also buoyed another idea for how to treat COVID-19—give patients the enzyme ACE2 as a decoy to direct SARS-CoV-2 away from their cells. A biotech company developing such an approach using recombinant ACE2 received regulatory approval today (April 2) to start clinical trials on COVID-19 patients.

“It’s a very interesting idea,” David Kass, a cardiologist at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine tells The Scientist. “Obviously, if the virus binds to this form of ACE2 that’s floating around in the bloodstream and not attached to a cell, it won’t be able to multiply and damage the cells.”

How ACE2 acts in the body

The ACE2 decoy idea can be traced back to early work on the receptor by Josef Penninger, a molecular immunologist at the University of British Columbia. Roughly 20 years ago, he was working as a researcher at the Ontario Cancer Institute when he cloned ACE2 and started probing what it does.

A senior investigator in the lab thought the work was a waste of time, Penninger recalls, telling him that scientists already knew everything they needed to know about the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure and fluid and electrolyte balance. The senior researcher added that ACE2, which is associated with the system, was so boring Penninger should stop working on it before he ruined his career. At the time, it was a painful comment to hear, but it made Penninger even more determined to understand ACE2’s biological function. “It’s funny now,” he says.

Over time, he and others started to unravel how ACE2 operates within the renin–angiotensin system. The system starts with a hormone secreted by the kidneys called renin that cleaves the peptide hormone angiotensinogen into angiotensin I. That cleavage product is then converted into a version of angiotensin II by ACE, the angiotensin-converting enzyme. That version binds to the angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor, on the surface of blood vessels, lung, and heart cells among other cells in the body. Where those molecules meet, blood vessels constrict and blood pressure rises, which can contribute to acute respiratory distress syndrome.

This is where ACE2 comes in. The enzyme cleaves an amino acid off angiotensin II to create angiotensin 1-7, which dilates blood vessels, reduces inflammation, and inactivates angiotensin II before it gets to a cell’s AT1 receptor.

“Whenever there is a hormone that has a certain interaction in the body, there’s often another hormone to counteract it,” Patel says. ACE2 counterbalances ACE, and “the body tries to maintain those two in balance to keep things in check.”

Doctors prescribe ACE inhibitors to people with high blood pressure and other heart problems to prevent ACE from converting angiotensin I into the form of angiotensin II that constricts blood vessels, leading to lower blood pressure. ARBs prevent angiotensin II from binding to AT1 receptors so ACE2 metabolizes it, also lowering blood pressure.

“We actually know a lot about ACE2 and its biology,” Penninger says. “We should follow the data.”

An ACE2 boost might distract the coronavirus

Penninger published his work on ACE2 biology in 2002, just before the outbreak of SARS in 2003. After the virus infected humans and started to spread, a team from Boston published the first clues to how SARS-CoV targets ACE2 to gain entry into human cells. There were other receptors proposed as entry points at that time, but the mention of ACE2 caught Penninger’s attention.

He started a study in mice, and in 2005 published the first definitive evidence that SARS-CoV uses ACE2 to infect its host’s cells. In the same study, Penninger and his colleagues showed that the virus reduces ACE2 abundance, which results in ramped-up angiotensin II levels, in turn causing acute lung failure. The work revealed what made SARS-CoV so deadly, he says.

Based on the data, Penninger’s team argued that administering a recombinant ACE2 protein could trick the virus into binding with it, rather than actual ACE2 receptors. This could then protect endogenous receptors and allow them to continue to function in counterbalancing ACE, and, ideally, protect the lung and heart from damage during a viral infection.

Penninger has been working on developing a recombinant ACE2 protein therapy for 15 years. He first tested it in mice after they’d inhaled acid; treatment with ACE2 prevented the animals from developing acute lung injury. Other studies showed the recombinant proteins could be used to treat heart failure, and eventually the research led to clinical trials to test ACE2’s safety in humans.

So far, early clinical trials of the drug have shown it does not have any harmful side effects in healthy humans or in patients with lung failure. (Penninger was not involved in conducting the clinical trial).

The next step is to see if the recombinant enzyme can intervene in a SARS-CoV-2 infection. In a study published today in Cell, Penninger’s group shows the drug can reduce the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in experimental models by a factor of 1,000 to 5,000. Today, Apeiron Biologics, the biotech company Penninger founded in 2005, was also awarded regulatory approval to start clinical trials to test the drug in patients with severe COVID-19 symptoms, which, he says, could happen as early as the end of next week.

Ramping up ACE2 using ARBs instead

Penninger’s early work on SARS-CoV is part of what prompted the discussion among physicians about the safety of ACE inhibitors and ARBs, which regulate levels of angiotensin II directly or via its cell receptor. Another study related to the antihypertensive drugs that got the doctors’ attention was one done by Ferrario more than a decade ago. Administering ACE inhibitors or ARBs to rats led to increased ACE2 activity in the animals’ hearts, exactly where scientists and physicians wouldn’t want more ACE2 receptors for SARS-CoV-2 to target. Or at least, that’s what one might think.

But Penninger’s preliminary work from 2005 implies that increasing ACE2 levels through antihypertensive drugs might treat symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with ARBs showing more promise than ACE inhibitors.

ACE inhibitors lower levels of angiotensin II, and when they do, there’s less substrate for ACE2 to metabolize, which could leave the enzyme idle and therefore open to attack by SARS-CoV-2. That’s part of the argument some researchers were making about ACE inhibitors contributing to COVID-19 infection. However, there are no data to show that happens, Penninger says. Still, he argues, the way ACE inhibitors work in the body, freeing up ACE2 on cells for viral targeting rules them out as potential COVID-19 treatments.

Using ARBs to combat the virus is a more promising approach. As Penninger’s team showed, SARS-CoV reduced the abundance of ACE2, causing hypertension and lung failure in mice. If ARBs boost ACE2 expression, that might counteract the effects of the infection. The hypothesis is preliminary at this point, says David Gurwitz, a geneticist with a background in pharmacology at Tel Aviv University. He described the idea, which seems paradoxical, March 4 in a review article published in Drug Development Research. The main difference between ACE inhibitors and ARBs is that the former just frees up existing ACE2 receptors, while the latter leads to an increase in the number of receptors, allowing more angiotensin II to be converted to angiotensin 1-7. That would dilate blood vessels and reduce inflammation, countering any hypertensive state caused by a viral infection.

In clinical analyses designed to ensure that ARBs don’t harm COVID-19 patients, researchers in China have published preliminary data on medRxiv supporting the hypothesis. In the study, the team tracked the health outcomes of 511 patients taking medications for heart conditions who then became infected with SARS-CoV-2. The patients took either ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or other drugs that lowered their blood pressure. The results showed that patients over age 65 taking ARBs were at a lower risk of developing severe lung damage than age-matched patients not taking the medications, but there weren’t enough data to do a similar analysis for ACE inhibitors. The work reveals there was no hazard for ARBs, and there may be benefits, but as always, more data are needed, Kass says.

One way to collect those data on a larger scale, Gurwitz explains, would be to analyze many more COVID-19 patients’ health records to see if they’ve been taking ARBs prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection, then comparing the severity of infection in those patients and how well they recovered with the symptoms of COVID-19 patients not taking the medications.

Gurwitz also recommends researchers compare the percentage of people chronically medicated with different antihypertensive medications in the general population with the percentage of them among hospital admissions for COVID-19. These types of analyses could also be done with many other approved drugs, he notes, not just ARBs.

Already, physicians at University Hospital Zurich have begun a patient registry to do these types of health informatics analyses, and physicians and researchers at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and other public health schools in the US have been discussing the feasibility of starting these studies.

“Unfortunately for the country, we’re going to have lots of COVID-19 cases,” Kass says. “Groups are now trying to get these epidemiological studies started so we can get answers.”

https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/blood-pressure-meds-point-the-way-to-possible-covid-19-treatment-67371?utm_campaign=TS_DAILY%20NEWSLETTER_2020&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=85706789&_hsenc=p2ANqtz–HTxdAA4l8ORpuJZQE3i–UqSCKXPaN4-_B2bIk8IV5pUfRvwjTqC8GIsP5hN1DJ4aIl7wJ54eQ0sjwTYqx2BbUBCqmA&_hsmi=85706789