by Emma Yasinski

Researchers at RIKEN and the University of Tokyo report the existence of a new class of proteins in Drosophila and human cell extracts that may serve as shields that protect other proteins from becoming damaged and causing disease. An excess of the proteins, known as Hero proteins, was associated with a 30 percent increase in the lifespan of Drosophila, according to the study, which was published last week (March 12) in PLOS Biology.

“The discovery of Hero proteins has far-reaching implications,” says Caitlin Davis, a chemist at Yale University who was not involved in the study, “and should be considered both at a basic science level in biochemistry assays and for applications as a potential stabilizer in protein-based pharmaceuticals.”

Nearly 10 years ago, Shintaro Iwasaki, then a graduate student studying biochemistry at the University of Tokyo, discovered a strangely heat-resistant protein in Drosophila that seemed to help stabilize another protein, Argonaute, in the face of high temperatures that would denature most proteins. Although he didn’t publish the work at the time, Iwasaki called the new type of protein a Heat-resistant obscure (Hero) protein—not because of their ability to rescue Argonaute from destruction, but because in Japan, the term “hero” means “weak or not rigid,” and Hero proteins don’t have stiff 3-D structures like other proteins do.

But recognition of a more widespread role for Hero proteins in protecting other molecules in the cell gives the name new meaning.

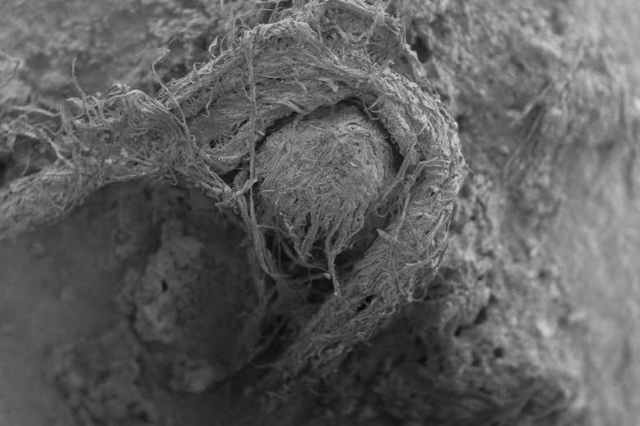

“It is generally assumed that proteins are folded into three-dimensional structures, which determine their functions,” says Kotaro Tsuboyama, a biochemist at the University of Tokyo and the lead author of the new study. But these 3-D structures are disrupted when the proteins are exposed to extreme conditions. When proteins are denatured, they lose the ability to function normally, and sometimes begin to aggregate, forming pathologic clumps that can lead to disease.

Hero proteins can survive these biologically challenging conditions. Heat-resistant proteins have been found in extremophiles—organisms known to live in extreme environments—but were thought to be rare in other organisms. In the new study, Tsuboyama and his team boiled lysates from Drosophila and human cell lines, identifying hundreds of Hero proteins that withstood the temperature.

The researchers selected six of these proteins and mixed them with “client” proteins—other functional proteins that on their own would be denatured by extreme conditions—before exposing them to high temperatures, drying, chemicals, and other harsh treatments. The Hero proteins prevented certain clients from losing their shape and function.

Next, the team tested the effects of Hero proteins in cellular models of two neurodegenerative disorders characterized by pathologic protein clumps: Huntington’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). When the Hero proteins were present, there was a significant reduction in protein clumping in both models.

“This is an extremely important finding as it may pave new therapeutic and preventive strategies for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases,” Morteza Mahmoudi, who studies regenerative medicine at Michigan State University and was not involved in the research, writes in an email to The Scientist.

Lastly, the team genetically engineered Drosophila to produce an excess of Hero proteins. These flies lived up to 30 percent longer than their wildtype counterparts.

Not everyone is convinced that the Hero proteins play a major protective role. “Although they show these proteins help their proven targets remain folded/shielded etc, I don’t think there’s a broader application at all,” Nihal Korkmaz, who designs proteins at the University of Washington Institute of Protein Design and also did not participate in the study, tells The Scientist in an email. She adds that many proteins she works with can withstand high temperatures and the researchers “don’t mention at all if [Hero proteins] are found throughout the brain or in CSF [cerebrospinal fluid],” where they’d be able to protect against Huntington’s or ALS.

The authors emphasized that there is a lot left to learn about the proteins. Each Hero protein seems able to protect some client proteins, but not all of them. Moreover, amino acid sequences differ considerably between Hero proteins, making it difficult to predict their functions. The researchers write in the study that they hope future studies will help them identify which clients each Hero might work with.

Whatever discoveries future work might hold, Tsuboyama says, the scientific community’s reaction to the team’s new study has been consistent: “Almost everyone says that Hero proteins are interesting but mysterious.”

K. Tsuboyama et al., “A widespread family of heat-resistant obscure (Hero) proteins protect against protein instability and aggregation,” PLOS Biol, doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3000632, 2020.