OUTRUNNING CANCER: Tumors on the lungs of sedentary mice (left) and animals that ran on wheels (right) after injection with melanoma cells.

L. PEDERSEN ET AL., CELL METAB, 2016

Bente Klarlund Pedersen

Mathilde was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 44. Doctors treated her with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, and Mathilde’s physician informed her that, among many other side effects of her cancer treatment, she could expect to lose muscle mass. To fight muscle wasting, Mathilde began the intensive physical training program offered to cancer patients at the Rigshospitalet University Hospital of Copenhagen. The program consists of 3.5-hour sessions of combined resistance and aerobic training, four times a week for six weeks. Although the chemotherapy made her tired, Mathilde (a friend of mine, not pictured, who requested I use her first name only) did not miss a single training session.

“In a way it felt counterintuitive to do intensive, hard training, while I was tired and nauseous, but I was convinced that the training was good for my physical and mental health and general wellbeing,” Mathilde told me in Danish. She followed the chemo- and radiotherapy strictly according to the prescribed schedule. She was not hospitalized, acquired no infections, and did not develop lymphedema, a failure of the lymphatic system that commonly occurs following breast cancer surgery and leads to swelling of the limbs.

Physical exercise is increasingly being integrated into the care of cancer patients such as Mathilde, and for good reason. Evidence is accumulating that exercise improves the wellbeing of these patients by combating the physical and mental deterioration that often occur during anticancer treatments. Most remarkably, we are beginning to understand that exercise can directly or indirectly fight the cancer itself.

An increasing amount of epidemiological literature strongly indicates that exercise training may lower the risk of cancer, control disease progression, amplify the effects of anticancer therapy, and improve physical function and psychosocial outcomes. For example, a 2016 study of more than 1.4 million individuals in the US and Europe found that people could reduce their cancer risk with moderate to vigorous leisure-time exercise training. The phenomenon held across several different cancers, including breast, colon, rectum, esophagus, lung, liver, kidney, bladder, and head and neck. And the combined results of approximately 700 unique exercise intervention trials, involving more than 50,000 cancer patients in total, leave little doubt that patients benefit from physical activity, showing improvements such as reduced toxicity of anticancer treatment, decreased disease progression, and enhanced survival. The same studies showed that exercise training improves mood, decreases loss of muscle mass, and helps cancer patients return to work earlier after successful treatment. Some studies show that 150 minutes per week of moderate exercise nearly double the chance of survival compared with breast cancer patients who don’t exercise during treatment.

Hundreds of animal studies, conducted over decades, suggest that the link is likely causal: in mice and rats, exercise leads to a reduction in the incidence, growth rate, and metastatic potential of cancer across a large variety of models of different human and murine tumor types. But how exercise helps fight cancer is a bit of a black box. Exercise may improve the efficacy of anticancer treatment by boosting the immune system and thereby attenuating the toxicity of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Cancer patients are also likely to benefit from the overall health-promoting properties of physical activity, such as improved metabolism and enhanced cardiovascular function.

Uncovering the mechanisms whereby exercise induces anticancer effects is crucial to fighting the disease. Exercise-related factors that have a direct or indirect anticancer effect could serve as valuable biomarkers for monitoring the amount, intensity, and type of exercise required to best aid cancer treatment. Such research could also potentially highlight novel therapeutic targets.

Each workout matters

Regardless of the nature of the training, the primary setting of exercise’s effect on cancer is the bloodstream. Long-term training has been associated with a reduction in the blood levels of systemic risk factors, such as sex hormones, insulin, and inflammatory molecules. However, this effect is only seen if exercise training is accompanied by weight loss, and researchers have not yet established causal direct links between regular exercise training and the reductions in the basal levels of these risk factors. Alternatively, the anticancer effect of exercise could also be the result of something that occurs within individual sessions of exercise, during which muscles are known to release spikes of various hormones and other factors into the blood.

To learn more about the effects of individual bouts of exercise versus long-term training regimens, Christine Dethlefsen, a graduate student in my laboratory, incubated breast cancer cells with serum obtained from cancer survivors at rest before and after a six-month training intervention that began after patients completed primary surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. For comparison, she incubated other cells with serum obtained from blood drawn from these patients immediately after a two-hour acute exercise session during their weeks-long course of chemotherapy. Her study revealed that serum obtained following an exercise session reduced the viability of the cultured breast cancer cells, while serum drawn at rest following six months of training had no effect.

These data suggest that cancer-fighting effects are driven by repeated acute exercise, and each bout matters. In Dethlefsen’s study, incubation with serum obtained after a single bout of exercise (consisting of 30 minutes of warm-up, 60 minutes of resistance training, and a 30-minute high-intensity interval spinning session) reduced breast cancer cell viability by only 10 to 15 percent compared with control cells incubated with serum obtained at rest. But a reduction in tumor cell viability by 10 to 15 percent several times a week may add up to clinically significant inhibition of tumor growth. Indeed, in a separate study, my colleagues and I found that daily, voluntary wheel running in mice inhibits tumor progression across a range of tumor models and anatomical locations, typically by more than 50 percent.

Exercise’s molecular messengers

One prime candidate for helping to explain the link between exercise and anticancer effects is a group of peptides known as myokines, which are produced and released by muscle cells. Several myokines are released only during exercise, and some researchers have proposed that these exercise-dependent myokines contribute to the myriad beneficial effects of physical activity for all individuals, not just cancer patients, perhaps by mediating crosstalk between the muscles and other parts of the body, including the liver, bones, fat, and brain.

Exercise’s Anticancer Mechanisms

Researchers are beginning to understand that not only can exercise improve cancer patients’ overall wellbeing during treatment, but it may also fight the cancer itself. Experiments on cultured cells and in mice hint at some of the mechanisms that may be involved in these direct and indirect effects.

1) Exercising muscles release multiple compounds known as myokines. Several of these have been shown to affect cancer cell proliferation in culture, and some, including interleukin-6, slow tumor growth in mice.

2) Exercise stimulates an increase in levels of the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine, which can both act directly on tumors and stimulate immune cells to enter the bloodstream.

3) Epinephrine also stimulates natural killer cells to enter circulation.

4) In mice, interleukin-6 appears to direct natural killer cells to home in on tumors.

5) In lab-grown cells and in mice, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and some myokines hinder tumor growth and metastasis.

The best-characterized myokine is interleukin-6, levels of which increase exponentially during exercise in humans. At least in mice, interleukin-6 is involved in directing natural killer (NK) cells to tumor sites. But there are approximately 20 known exercise-induced myokines, and the list continues to grow. Preliminary studies show that myokines can reduce cancer growth in cell culture and in mice. For example, when treated with irisin, a myokine best known for its ability to convert white fat into brown fat, cultured breast cancer cells were more likely to lose viability and undergo apoptosis than were control cells. A study I led found that oncostatin M, another myokine that is upregulated in murine muscles after exercise, also inhibits breast cancer proliferation in vitro. And a team led by Toshikazu Yoshikawa of Kyoto Prefectural University determined that in a mouse model of colon cancer, a myokine known as secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) reduced tumorigenesis in the colon of exercising mice. Overall, skeletal muscle cells may be secreting several hundred myokine types, but of these, only about 5 percent have been investigated for their biological effects. And researchers have tested fewer for whether they regulate cancer cell growth.

Not all of the molecular messengers released in response to exercise come from the muscles. Notably, exercise induces acute increases in epinephrine and norepinephrine, stress hormones released from the adrenal gland that are involved in recruiting NK cells in humans. Murine studies show that NK cells can signal directly to cancer cells. In Dethlefsen’s study, when breast cancer cells incubated with serum obtained after a bout of exercise were then injected into mice, they showed reduced tumor formation. The exercise-induced suppression of breast cancer cell viability and tumor formation were, however, completely blunted when we blockaded β-adrenergic signaling, the pathway through which epinephrine and norepinephrine work. These findings suggested that epinephrine and norepinephrine are responsible for the cancer-inhibiting effects we observed. Epinephrine and norepinephrine, which activate NK cells, have also been shown to act on cancer cells through the Hippo signaling pathway, which is known for regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. Exercise-induced spikes in these stress hormones activate this pathway, which somehow inhibits the formation of new malignant tumors associated with metastatic processes.

Calling the immune system

In addition to acting directly on tumors, the myokines released during and after exercise are known to mobilize immune cells, particularly NK cells, which appear to be instrumental to the exercise-mediated control of tumor growth in mice.

The late molecular biologist Pernille Højman of the Centre for Physical Activity Research at Rigshospitalet was a leader in discerning this mechanism. In the study described above that compared tumor growth in active and sedentary mice, on which I was also an author, Højman looked more closely at the tumors and found that the running mice had twice as many cytotoxic T cells and five times more NK cells than those animals housed without a wheel.

Højman repeated the experiment on mice that had been engineered to lack cytotoxic T cells. Again, she found that mice with access to running wheels had smaller tumors. When she performed the same test on mice that had intact T cells but lacked NK cells, the tumors of all the mice grew to the same size. This suggested that the NK cells, and not the T cells, were the link between exercise and tumor growth suppression.

Work by other groups had demonstrated that epinephrine has the potential to mobilize NK cells, and Højman and the rest of our team wondered if epinephrine had a role in mediating the anticancer effects of exercise. We injected mice that had malignant melanoma with either epinephrine or saline and found that the hormone indeed reduced the growth of tumors, but to a lesser degree than what was observed in the mice that had access to a wheel. Something else had to be involved.

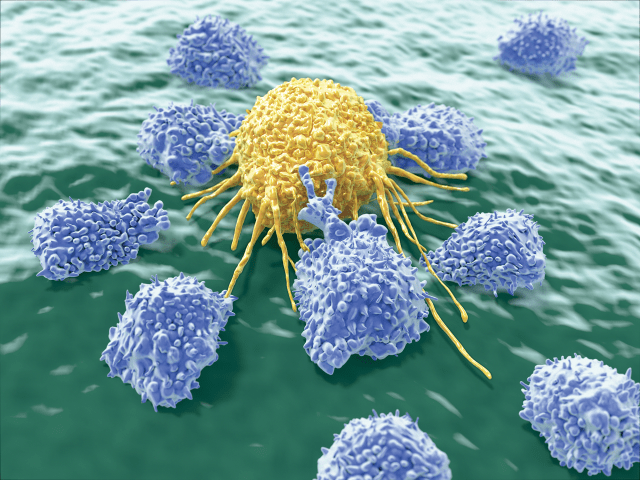

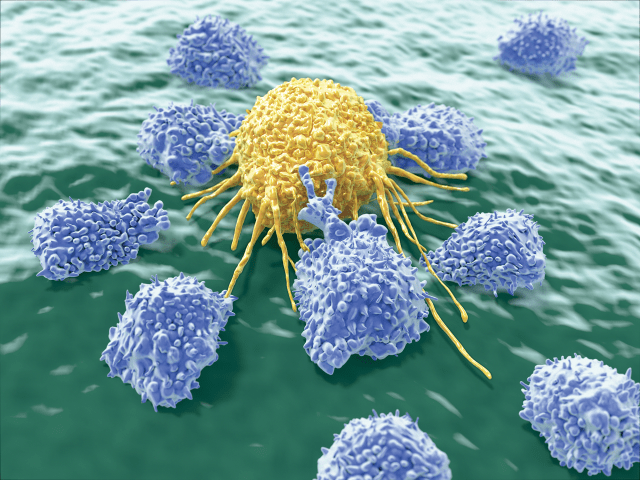

AND STAY OUT: Exercise activates natural killer cells (purple) and helps them home to tumors.

To find out what, our team tested the effects of interleukin-6, which we suspected was the additional exercise factor involved in tumor homing of immune cells. When we exposed inactive mice to both epinephrine and interleukin-6, the rodents’ immune systems attacked the tumors as effectively as if the animals had been running.

While much remains to be learned about how physical exercise influences cancer, evidence shows that exercise training is safe and feasible for patients with the disease and contributes to their physical and psychosocial health. (See “Exercise and Depression” on page 44.) Being active may even delay disease progression and improve survival. A growing number of patients, including Mathilde, are undergoing exercise training to fight physical deterioration during cancer treatment. As they do so, scientists are working hard to understand the pathways by which physical activity results in anticancer activity.

Exercise and Depression

Depression is a severe adverse effect of cancer and cancer therapy. The risk of depression can be as high as 50 percent for some cancer diagnoses, although this number varies a great deal depending on cancer type and stage (J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr, 32:57–71, 2004). In addition to its effects on a patient’s quality of life, depression can hinder compliance with treatment, and it’s a risk factor for mortality in cancer patients (Lancet, 356:1326–27, 2000). In recent years, healthcare providers have increasingly integrated physical exercise into the care of cancer patients with the aim of controlling disease and lessening treatment-related side effects, while researchers have amassed evidence supporting the assertion that such training can lower symptoms of depression in these patients (Acta Oncol, 58:579–87, 2019). The biological mechanisms behind this beneficial effect remain to be determined, although some clues have emerged.

For example, a study in mice found that exercise-dependent changes in metabolism result in reduced accumulation of some neurotoxic products (Cell, 159:33-45, 2014). In cancer patients, systemic levels of kynurenine, a neurotoxic metabolite associated with fatigue and depression, are upregulated (Cancer, 121:2129-36, 2015). In mice, exercise enhances the expression of the enzyme kynurenine aminotransferase, which converts kynurenine into neuroprotective kynurenic acid, thereby reducing depression-like symptoms.

Findings such as these, together with exercise’s well-documented effects in alleviating depression among patients without cancer, suggest that incorporating exercise into cancer treatment may benefit mental as well as physical health.

https://www.the-scientist.com/features/regular-exercise-helps-patients-combat-cancer-67317?utm_campaign=TS_DAILY%20NEWSLETTER_2020&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email&utm_content=86607989&_hsenc=p2ANqtz-8W-OrX7bn_MULo5_Jx-u7E1c2gVfZwwWCD26RHtjZT7CoZ9KWhz0zOuCD53QkfOvre5WKYWWxP0plIm4Lf56uABjYb0A&_hsmi=86607989