By Brian Handwerk, National Geographic

Various forms of Mother’s Day have been around for more than a century, with different figures and organizations doing battle over who really founded the holiday.

The story of the modern holiday—which is celebrated this Sunday in the United States and many other nations—is rife with controversy, conflict, and consumerism run amok. Some strange-but-true facts you probably don’t know:

1. Mother’s Day started as an anti-war movement.

Anna Jarvis is most often credited with founding Mother’s Day in the United States.

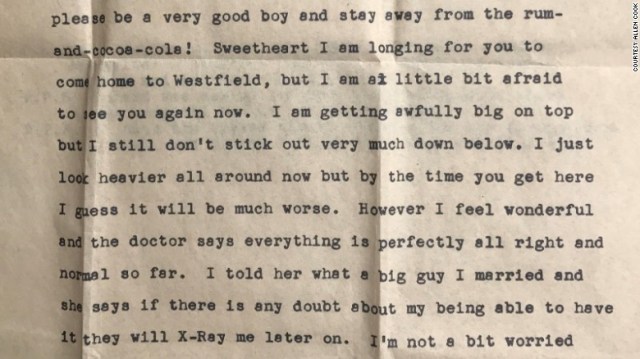

Designated as the second Sunday in May by President Woodrow Wilson in 1914, aspects of that holiday have since spread overseas, sometimes mingling with local traditions. Jarvis took great pains to acquire and defend her role as “Mother of Mother’s Day,” and to focus the day on children celebrating their mothers.

But others had the idea first, and with different agendas.

Julia Ward Howe, better known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” promoted a Mothers’ Peace Day beginning in 1872. For Howe and other antiwar activists, including Anna Jarvis’s mother, Mother’s Day was a way to promote global unity after the horrors of the American Civil War and Europe’s Franco-Prussian War.

“Howe called for women to gather once a year in parlors, churches, or social halls, to listen to sermons, present essays, sing hymns or pray if they wished—all in the name of promoting peace,” said Katharine Antolini, an historian at West Virginia Wesleyan College and author of Memorializing Motherhood: Anna Jarvis and the Struggle for Control of Mother’s Day.

Several American cities including Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago held annual June 2nd Mothers’ Day services until roughly 1913, Antolini says.

These early Mother’s Day movements became popular only among peace activist groups and faded when other promoters took center stage.

2. A former football coach promoted an early version of Mother’s Day—and was accused of “kidnapping” the holiday.

Frank Hering, a former football coach and faculty member at University of Notre Dame, also proposed the idea of a Mother’s Day before Anna Jarvis. In 1904 Hering urged an Indianapolis gathering of the Fraternal Order of Eagles to support “setting aside of one day in the year as a nationwide memorial to the memory of Mothers and motherhood.”

Hering didn’t suggest a specific day or month for the observance, though he did note a preference for Mother’s Day falling on a Sunday. Local “aeries” of the Fraternal Order of Eagles took up Hering’s challenge. Today the organization still bills Hering and the Eagles as the “true founders of Mother’s Day.”

Anna Jarvis did not like the thought of Mother’s Day having a “father” in Hering. She blasted him in an undated 1920s statement entitled “Kidnapping Mother’s Day: Will You Be an Accomplice?”

“Do me the justice of refraining from furthering the selfish interests of this claimant,” Jarvis wrote, “who is making a desperate effort to snatch from me the rightful title of originator and founder of Mother’s Day, established by me after decades of untold labor, time, and expense.”

Antolini says that Jarvis, who never had children, was acting partly out of ego: “Everything she signed was Anna Jarvis, Founder of Mother’s Day. It was who she was.”

3. FDR designed a Mother’s Day stamp. Or at least he tried.

Woodrow Wilson wasn’t the only president to put his stamp on Mother’s Day. Franklin Delano Roosevelt personally designed a 1934 postage stamp to commemorate the day.

The president co-opted a stamp that was originally meant to honor 19th-century painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler and featured the artist’s famed “Whistler’s Mother” portrait , of Anna McNeill Whistler. FDR surrounded the iconic maternal image with a dedication: “IN MEMORY AND IN HONOR OF THE MOTHERS OF AMERICA.”

Anna Jarvis didn’t approve of the design and refused to allow the words “Mother’s Day” to appear on the stamp—so they never did. “Overall, she thought the stamp ugly,” Antolini says.

4. Mother’s Day’s founder hated those who fundraised off the holiday.

Since Mother’s Day’s early years, some groups have seized on it as a chance to raise funds for various charitable causes—including mothers in need. Anna Jarvis hated that.

“She called those charities Christian pirates,” Antolini said. “Today most of us would think it was wonderful to use the day to raise funds to support poor mothers or families of World War I veterans or another worthy group but she hated them for that.”

Much of the reason why, Antolini says, is that in the days before charity watchdog organizations Jarvis simply didn’t trust fundraisers to deliver the money to the people it was supposed to help. “She resented the idea that profiteers would use the day as just another way of making money,” Antolini says.

5. The mother of Mother’s Day lost everything in fight to protect her holiday.

It didn’t take long for Anna Jarvis’s Mother’s Day to get commercialized, with Jarvis fighting against what it became.

“To have Mother’s Day the burdensome, wasteful, expensive gift day that Christmas and other special days have become, is not our pleasure,” she wrote in the 1920s. “If the American people are not willing to protect Mother’s Day from the hordes of money schemers that would overwhelm it with their schemes, then we shall cease having a Mother’s Day—and we know how.”

Jarvis never profited from the day, despite ample opportunities afforded by her status as a minor celebrity. In fact, she went broke using what monies she had battling the holiday’s commercialization.

In poor health and with her emotional stability in question, she died penniless at age 84 after living the last four years of her life in the Marshall Square Sanitarium, Antolini says.

6. Courts Heard “Custody Battles” Over Mother’s Day

Anna Jarvis always considered Mother’s Day her intellectual and legal property and wasn’t afraid to lawyer up in its defense.

She included a warning on some Mother’s Day International Association Press releases: “Any charity, institution, hospital, organization, or business using Mother’s Day names, work, emblem, or celebration for getting money, making sales or on printed forms should be held as imposters by proper authorities, and reported to this association.”

Antolini says it’s difficult to determine from scattered court documents just how litigious Jarvis was, but a 1944 Newsweek article reported that she once had as many as 33 simultaneously pending Mother’s Day lawsuits.

7. Flowers are an original tradition that endures (sort of).

The white carnation, the favorite flower of Anna Jarvis’s mother, was the original flower of Mother’s Day.

“The carnation does not drop its petals, but hugs them to its heart as it dies, and so, too, mothers hug their children to their hearts, their mother love never dying,” Jarvis explained in a 1927 interview.

The most popular flower choice today seems to be “mom’s favorite.”

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150507-mothers-day-history-holidays-anna-jarvis/