by JAMES VLAHOS

The first voice you hear on the recording is mine. “Here we are,” I say. My tone is cheerful, but a catch in my throat betrays how nervous I am.

Then, a little grandly, I pronounce my father’s name: “John James Vlahos.”

“Esquire,” a second voice on the recording chimes in, and this one word—delivered as a winking parody of lawyerly pomposity—immediately puts me more at ease. The speaker is my dad. We are sitting across from each other in my parents’ bedroom, him in a rose-colored armchair and me in a desk chair. It’s the same room where, decades ago, he calmly forgave me after I confessed that I’d driven the family station wagon through a garage door. Now it’s May 2016, he is 80 years old, and I am holding a digital audio recorder.

Sensing that I don’t quite know how to proceed, my dad hands me a piece of notepaper marked with a skeletal outline in his handwriting. It consists of just a few broad headings: “Family History.” “Family.” “Education.” “Career.” “Extracurricular.”

“So … do you want to take one of these categories and dive into it?” I ask.

“I want to dive in,” he says confidently. “Well, in the first place, my mother was born in the village of Kehries—K-e-h-r-i-e-s—on the Greek island of Evia …” With that, the session is under way.

We are sitting here, doing this, because my father has recently been diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. The disease has metastasized widely throughout his body, including his bones, liver, and brain. It is going to kill him, probably in a matter of months.

So now my father is telling the story of his life. This will be the first of more than a dozen sessions, each lasting an hour or more. As my audio recorder runs, he describes how he used to explore caves when he was growing up; how he took a job during college loading ice blocks into railroad boxcars. How he fell in love with my mother, became a sports announcer, a singer, and a successful lawyer. He tells jokes I’ve heard a hundred times and fills in biographical details that are entirely new to me.

Three months later, my younger brother, Jonathan, joins us for the final session. On a warm, clear afternoon in the Berkeley hills, we sit outside on the patio. My brother entertains us with his favorite memories of my dad’s quirks. But as we finish up, Jonathan’s voice falters. “I will always look up to you tremendously,” he says, his eyes welling up. “You are always going to be with me.” My dad, whose sense of humor has survived a summer of intensive cancer treatments, looks touched but can’t resist letting some of the air out of the moment. “Thank you for your thoughts, some of which are overblown,” he says. We laugh, and then I hit the stop button.

In all, I have recorded 91,970 words. When I have the recordings professionally transcribed, they will fill 203 single-spaced pages with 12-point Palatino type. I will clip the pages into a thick black binder and put the volume on a bookshelf next to other thick black binders full of notes from other projects.

But by the time I put that tome on the shelf, my ambitions have already moved beyond it. A bigger plan has been taking shape in my head. I think I have found a better way to keep my father alive.

It’s 1982, and I’m 11 years old, sitting at a Commodore PET computer terminal in the atrium of a science museum near my house. Whenever I come here, I beeline for this machine. The computer is set up to run a program called Eliza—an early chatbot created by MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum in the mid-1960s. Designed to mimic a psychotherapist, the bot is surprisingly mesmerizing.

What I don’t know, sitting there glued to the screen, is that Weizenbaum himself took a dim view of his creation. He regarded Eliza as little more than a parlor trick (she is one of those therapists who mainly just echoes your own thoughts back to you), and he was appalled by how easily people were taken in by the illusion of sentience. “What I had not realized,” he wrote, “is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

At age 11, I am one of those people. Eliza astounds me with responses that seem genuinely perceptive (“Why do you feel sad?”) and entertains me with replies that obviously aren’t (“Do you enjoy feeling sad?”). Behind that glowing green screen, a fledgling being is alive. I’m hooked.

A few years later, after taking some classes in Basic, I try my hand at crafting my own conversationally capable computer program, which I ambitiously call The Dark Mansion. Imitating classic text-only adventure games like Zork, which allow players to control an unfolding narrative with short typed commands, my creation balloons to hundreds of lines and actually works. But the game only lasts until a player navigates to the front door of the mansion—less than a minute of play.

Decades go by, and I prove better suited to journalism than programming. But I am still interested in computers that can talk. In 2015 I write a long article for The New York Times Magazine about Hello Barbie, a chatty, artificially intelligent update of the world’s most famous doll. In some ways, this new Barbie is like Eliza: She “speaks” via a prewritten branching script, and she “listens” via a program of pattern-matching and natural-language processing. But where Eliza’s script was written by a single dour German computer scientist, Barbie’s script has been concocted by a whole team of people from Mattel and PullString, a computer conversation company founded by alums of Pixar. And where Eliza’s natural-language processing abilities were crude at best, Barbie’s powers rest on vast recent advances in machine learning, voice recognition, and processing power. Plus Barbie—like Amazon’s Alexa, Apple’s Siri, and other products in the “conversational computing” boom—can actually speak out loud in a voice that sounds human.

I keep in touch with the PullString crew afterward as they move on to creating other characters (for instance, a Call of Duty bot that, on its first day in the wild, has 6 million conversations). At one point the company’s CEO, Oren Jacob, a former chief technology officer at Pixar, tells me that PullString’s ambitions are not limited to entertainment. “I want to create technology that allows people to have conversations with characters who don’t exist in the physical world—because they’re fictional, like Buzz Lightyear,” he says, “or because they’re dead, like Martin Luther King.”

My father receives his cancer diagnosis on April 24, 2016. A few days later, by happenstance, I find out that PullString is planning to publicly release its software for creating conversational agents. Soon anybody will be able to access the same tool that PullString has used to create its talking characters.

The idea pops into my mind almost immediately. For weeks, amid my dad’s barrage of doctor’s appointments, medical tests, and treatments, I keep the notion to myself.

I dream of creating a Dadbot—a chatbot that emulates not a children’s toy but the very real man who is my father. And I have already begun gathering the raw material: those 91,970 words that are destined for my bookshelf.

The thought feels impossible to ignore, even as it grows beyond what is plausible or even advisable. Right around this time I come across an article online, which, if I were more superstitious, would strike me as a coded message from forces unseen. The article is about a curious project conducted by two researchers at Google. The researchers feed 26 million lines of movie dialog into a neural network and then build a chatbot that can draw from that corpus of human speech using probabilistic machine logic. The researchers then test the bot with a bunch of big philosophical questions.

“What is the purpose of living?” they ask one day.

The chatbot’s answer hits me as if it were a personal challenge.

“To live forever,” it says.

“Sorry,” my mom says for at least the third time. “Can you explain what a chatbot is?” We are sitting next to each other on a couch in my parents’ house. My dad, across the room in a recliner, looks tired, as he increasingly does these days. It is August now, and I have decided it is time to tell them about my thoughts.

As I have contemplated what it would mean to build a Dadbot (the name is too cute given the circumstances, but it has stuck in my head), I have sketched out a list of pros and cons. The cons are piling up. Creating a Dadbot precisely when my actual dad is dying could be agonizing, especially as he gets even sicker than he is now. Also, as a journalist, I know that I might end up writing an article like, well, this one, and that makes me feel conflicted and guilty. Most of all, I worry that the Dadbot will simply fail in a way that cheapens our relationship and my memories. The bot may be just good enough to remind my family of the man it emulates—but so far off from the real John Vlahos that it gives them the creeps. The road I am contemplating may lead straight to the uncanny valley.

So I am anxious to explain the idea to my parents. The purpose of the Dadbot, I tell them, would simply be to share my father’s life story in a dynamic way. Given the limits of current technology and my own inexperience as a programmer, the bot will never be more than a shadow of my real dad. That said, I would want the bot to communicate in his distinctive manner and convey at least some sense of his personality. “What do you think?” I ask.

My dad gives his approval, though in a vague, detached way. He has always been a preternaturally upbeat, even jolly guy, but his terminal diagnosis is nudging him toward nihilism. His reaction to my idea is probably similar to what it would be if I told him I was going to feed the dog—or that an asteroid was bearing down upon civilization. He just shrugs and says, “OK.”

The responses of other people in my family—those of us who will survive him—are more enthusiastic. My mom, once she has wrapped her mind around the concept, says she likes the idea. My siblings too. “Maybe I am missing something here,” my sister, Jennifer, says. “Why would this be a problem?” My brother grasps my qualms but doesn’t see them as deal breakers. What I am proposing to do is definitely weird, he says, but that doesn’t make it bad. “I can imagine wanting to use the Dadbot,” he says.

That clinches it. If even a hint of a digital afterlife is possible, then of course the person I want to make immortal is my father.

This is my dad: John James Vlahos, born January 4, 1936. Raised by Greek immigrants, Dimitrios and Eleni Vlahos, in Tracy, California, and later in Oakland. Phi Beta Kappa graduate (economics) from UC Berkeley; sports editor of The Daily Californian. Managing partner of a major law firm in San Francisco. Long-suffering Cal sports fan. As an announcer in the press box at Berkeley’s Memorial Stadium, he attended all but seven home football games between 1948 and 2015. A Gilbert and Sullivan fanatic, he has starred in shows like H.M.S. Pinafore and was president of the Lamplighters, a light-opera theater company, for 35 years. My dad is interested in everything from languages (fluent in English and Greek, decent in Spanish and Italian) to architecture (volunteer tour guide in San Francisco). He’s a grammar nerd. Joke teller. Selfless husband and father.

These are the broad outlines of the life I hope to codify inside a digital agent that will talk, listen, and remember. But first I have to get the thing to say anything at all. In August 2016, I sit down at my computer and fire up PullString for the first time.

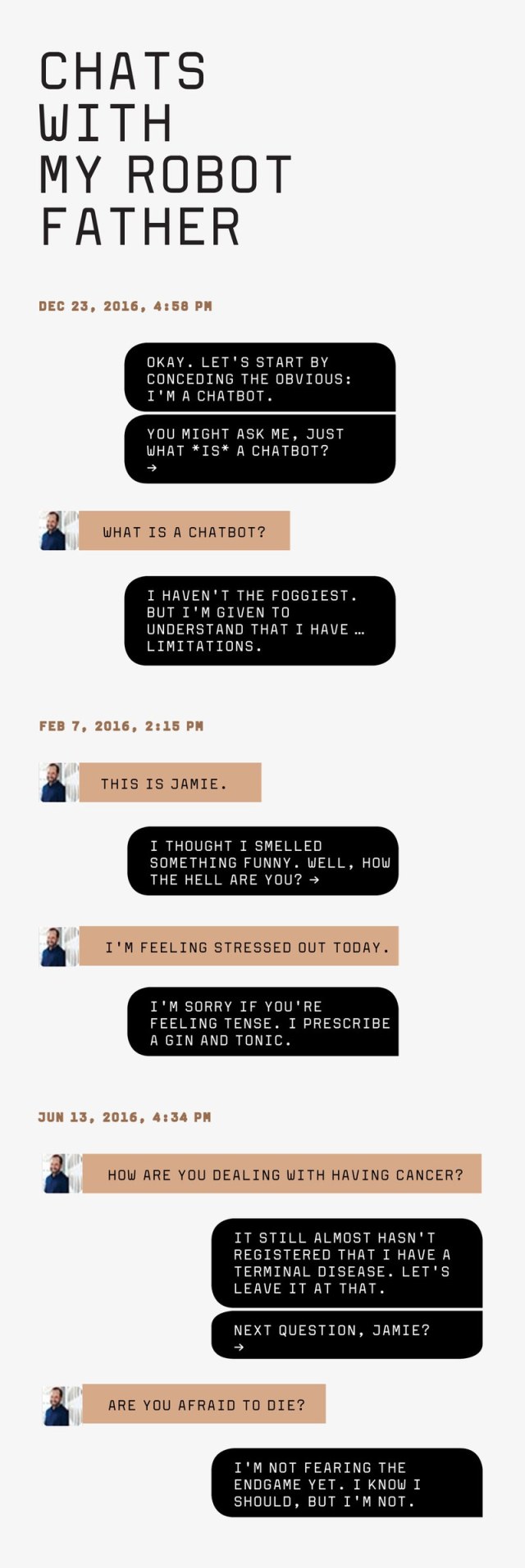

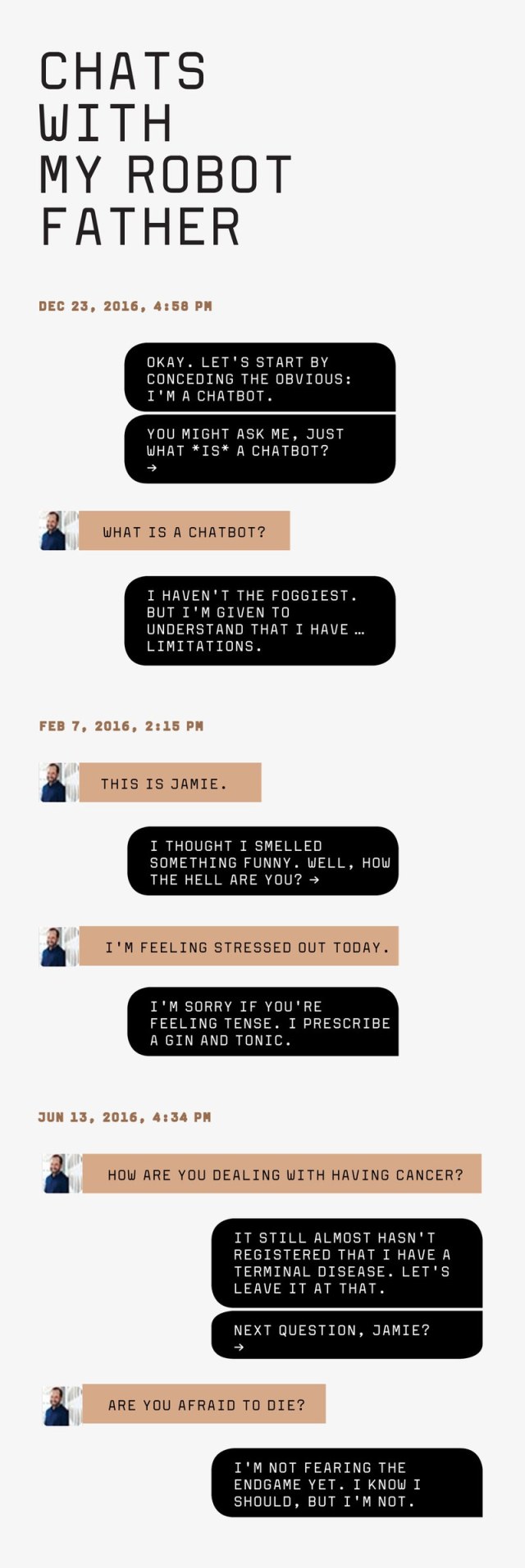

To make the amount of labor feasible, I have decided that, at least initially, the Dadbot will converse with users via text messages only. Not sure where to begin programming, I type, “How the hell are you?” for the Dadbot to say. The line appears onscreen in what looks like the beginning of a giant, hyper-organized to-do list and is identified by a yellow speech bubble icon.

Now, having lobbed a greeting out into the world, it’s time for the Dadbot to listen. This requires me to predict possible responses a user might type, and I key in a dozen obvious choices—fine, OK, bad, and so on. Each of these is called a rule and is tagged with a green speech bubble. Under each rule, I then script an appropriate follow-up response; for example, if a user says, “great,” I tell the bot to say, “I’m glad to hear that.” Lastly, I create a fallback, a response for every input that I haven’t predicted—e.g., “I’m feeling off-kilter today.” The PullString manual advises that after fallbacks, the bot response should be safely generic, and I opt for “So it goes.”

With that, I have programmed my very first conversational exchange, accounting for multiple contingencies within the very narrow context of saying hello.

And voilà, a bot is born.

Granted, it is what Lauren Kunze, CEO of Pandorabots, would call a “crapbot.” As with my Dark Mansion game back in the day, I’ve just gotten to the front door, and the path ahead of me is dizzying. Bots get good when their code splits apart like the forks of a giant maze, with user inputs triggering bot responses, each leading to a fresh slate of user inputs, and so on until the program has thousands of lines. Navigational commands ping-pong the user around the conversational structure as it becomes increasingly byzantine. The snippets of speech that you anticipate a user might say—the rules—can be written elaborately, drawing on deep banks of phrases and synonyms governed by Boolean logic. Rules can then be combined to form reusable meta-rules, called intents, to interpret more complex user utterances. These intents can even be generated automatically, using the powerful machine-learning engines offered by Google, Facebook, and PullString itself. Beyond that, I also have the option of allowing the Dadbot to converse with my family out loud, via Alexa (though unnervingly, his responses would come out in her voice).

It will take months to learn all of these complexities. But my flimsy “How are you” sequence has nonetheless taught me how to create the first atoms of a conversational universe.

After a couple of weeks getting comfortable with the software, I pull out a piece of paper to sketch an architecture for the Dadbot. I decide that after a little small talk to start a chat session, the user will get to choose a part of my dad’s life to discuss. To denote this, I write “Conversation Hub” in the center of the page. Next, I draw spokes radiating to the various chapters of my Dad’s life—Greece, Tracy, Oakland, College, Career, etc. I add Tutorial, where first-time users will get tips on how best to communicate with the Dadbot; Songs and Jokes; and something I call Content Farm, for stock segments of conversations that will be referenced from throughout the project.

To fill these empty buckets, I mine the oral history binder, which entails spending untold hours steeped in my dad’s words. The source material is even richer than I’d realized. Back in the spring, when my dad and I did our interviews, he was undergoing his first form of cancer treatment: whole-brain radiation. This amounted to getting his head microwaved every couple of weeks, and the oncologist warned that the treatments might damage his cognition and memory. I see no evidence of that now as I look through the transcripts, which showcase my dad’s formidable recall of details both important and mundane. I read passages in which he discusses the context of a Gertrude Stein quote, how to say “instrumentality” in Portuguese, and the finer points of Ottoman-era governance in Greece. I see the names of his pet rabbit, the bookkeeper in his father’s grocery store, and his college logic professor. I hear him recount exactly how many times Cal has been to the Rose Bowl and which Tchaikovsky piano concerto his sister played at a high school recital. I hear him sing “Me and My Shadow,” which he last performed for a high school drama club audition circa 1950.

All of this material will help me to build a robust, knowledgeable Dadbot. But I don’t want it to only represent who my father is. The bot should showcase how he is as well. It should portray his manner (warm and self-effacing), outlook (mostly positive with bouts of gloominess), and personality (erudite, logical, and above all, humorous).

The Dadbot will no doubt be a paltry, low-resolution representation of the flesh-and-blood man. But what the bot can reasonably be taught to do is mimic how my dad talks—and how my dad talks is perhaps the most charming and idiosyncratic thing about him. My dad loves words—wry, multisyllabic ones that make him sound like he is speaking from the pages of a P. G. Wodehouse novel. He employs antiquated insults (“Poltroon!”) and coins his own (“He flames from every orifice”). My father has catchphrases. If you say something boastful, he might sarcastically reply, “Well, hot dribbling spit.” A scorching summer day is “hotter than a four-dollar fart.” He prefaces banal remarks with the faux-pretentious lead-in “In the words of the Greek poet …” His penchant for Gilbert and Sullivan quotes (“I see no objection to stoutness, in moderation”) has alternately delighted and exasperated me for decades.

Using the binder, I can stock my dad’s digital brain with his actual words. But personality is also revealed by what a person chooses not to say. I am reminded of this when I watch how my dad handles visitors. After whole-brain radiation, he receives aggressive chemotherapy throughout the summer. The treatments leave him so exhausted that he typically sleeps 16 or more hours a day. But when old friends propose to visit during what should be nap time, my dad never objects. “I don’t want to be rude,” he tells me. This tendency toward stoic self-denial presents a programming challenge. How can a chatbot, which exists to gab, capture what goes unsaid?

Weeks of work on the Dadbot blend into months. The topic modules—e.g., College—swell with nested folders of subtopics, like Classes, Girlfriends, and The Daily Cal. To stave off the bot vice of repetitiousness, I script hundreds of variants for recurring conversational building blocks like Yes and What would you like to talk about? and Interesting. I install a backbone of life facts: where my dad lives, the names of his grandchildren, and the year his mother died. I encode his opinions about beets (“truly vomitous”) and his description of UCLA’s school colors (“baby-shit blue and yellow.”)

When PullString adds a feature that allows audiofiles to be sent in a messaging thread, I start sprinkling in clips of my father’s actual voice. This enables the Dadbot to do things like launch into a story he made up when my siblings and I were small—that of Grimo Gremeezi, a little boy who hated baths so much that he was accidentally hauled off to the dump. In other audio segments, the bot sings Cal spirit songs—the profane “The Cardinals Be Damned” is a personal favorite—and excerpts from my dad’s Gilbert and Sullivan roles.

Veracity concerns me. I scrutinize lines that I have scripted for the bot to say, such as “Can you guess which game I am thinking of?” My father is just the sort of grammar zealot who would never end a sentence with a preposition, so I change that line to “Can you guess which game I have in my mind?” I also attempt to encode at least a superficial degree of warmth and empathy. The Dadbot learns how to respond differently to people depending on whether they say they feel good or bad—or glorious, exhilarated, crazed, depleted, nauseous, or concerned.

I try to install spontaneity. Rather than wait for the user to make all of the conversational choices, the Dadbot often takes the lead. He can say things like “Not that you asked, but here is a little anecdote that just occurred to me.” I also give the bot a skeletal sense of time. At midday, for instance, it might say, “I am always happy to talk, but shouldn’t you be eating lunch around now?” Now that temporal awareness is part of the bot’s programming, I realize that I need to code for the inevitable. When I teach the bot holidays and family birthdays, I find myself scripting the line “I wish I could be there to celebrate with you.”

I also wrestle with uncertainties. In the oral history interviews, a question of mine might be followed by five to 10 minutes of my dad talking. But I don’t want the Dadbot to deliver monologues. How much condensing and rearranging of his words is OK? I am teaching the bot what my dad has actually said; should I also encode remarks that he likely would say in certain situations? How can I mitigate my own subjectivity as the bot’s creator—and ensure that it feels authentic to my whole family and not just to me? Does the bot uniformly present itself as my actual dad, or does it ever break the fourth wall and acknowledge that it is a computer? Should the bot know that he (my dad) has cancer? Should it be able to empathetically respond to our grief or to say “I love you”?

In short, I become obsessed. I can imagine the elevator pitch for this movie: Man fixated on his dying father tries to keep him robotically alive. Stories about synthesizing life have been around for millennia, and everyone knows they end badly. Witness the Greek myth of Prometheus, Jewish folkloric tales about golems, Frankenstein, Ex Machina, and The Terminator. The Dadbot, of course, is unlikely to rampage across the smoking, post-Singularity wastes of planet Earth. But there are subtler dangers than that of a robo-apocalypse. It is my own sanity that I’m putting at risk. In dark moments, I worry that I’ve invested hundreds of hours creating something that nobody, maybe not even I, will ultimately want.

To test the Dadbot, I have so far only exchanged messages in PullString’s Chat Debugger window. It shows the conversation as it unfolds, but the lines of code are visible in another, larger box above it. This is like watching a magician perform a trick while he simultaneously explains how it works. Finally, one morning in November, I publish the Dadbot to what will be its first home—Facebook Messenger.

Tense, I pull out my phone and select the Dadbot from a list of contacts. For a few seconds, all I see is a white screen. Then, a gray text bubble pops up with a message. The moment is one of first contact.

“Hello!” the Dadbot says. “‘Tis I, the Beloved and Noble Father!”

Shortly after the dadbot takes its first steps into the wild, I go to visit a UC Berkeley student named Phillip Kuznetsov. Unlike me, Kuznetsov formally studies computer science and machine learning. He belongs to one of the 18 academic teams competing for Amazon’s inaugural Alexa Prize. It’s a $2.5 million payout to the competitors who come closest to the starry-eyed goal of building “a socialbot that can converse coherently and engagingly with humans on popular topics for 20 minutes.” I should feel intimidated by Kuznetsov’s credentials but don’t. Instead, I want to show off. Handing Kuznetsov my phone, I invite him to be the first person other than me to talk to the Dadbot. After reading the opening greeting, Kuznetsov types, “Hello, Father.”

To my embarrassment, the demo immediately derails. “Wait a second. John who?” the Dadbot nonsensically replies. Kuznetsov laughs uncertainly, then types, “What are you up to?”

“Sorry, I can’t field that one right now,” the Dadbot says.

The Dadbot redeems itself over the next few minutes, but only partially. Kuznetsov plays rough, saying things I know the bot can’t understand, and I am overcome with parental protectiveness. It’s what I felt when I brought my son Zeke to playgrounds when he was a wobbly toddler—and watched, aghast, as older kids careened brutishly around him.

The next day, recovering from the flubbed demo, I decide that I need more of the same medicine. Of course the bot works well when I’m the one testing it. I decide to show the bot to a few more people in coming weeks, though not to anyone in my family—I want it to work better before I do that. The other lesson I take away is that bots are like people: Talking is generally easy; listening well is hard. So I increasingly focus on crafting highly refined rules and intents, which slowly improve the Dadbot’s comprehension.

The work always ultimately leads back to the oral history binder. Going through it as I work, I get to experience my dad at his best. This makes it jarring when I go to visit the actual, present-tense version of my dad, who lives a few minutes from my house. He is plummeting away.

At one dinner with the extended family, my father face-plants on a tile floor. It is the first of many such falls, the worst of which will bloody and concuss him and require frantic trips to the emergency room. With his balance and strength sapped by cancer, my dad starts using a cane, and then a walker, which enables him to take slow-motion walks outside. But even that becomes too much. When simply getting from his bed to the family room constitutes a perilous expedition, he switches to a wheelchair.

Chemotherapy fails, and in the fall of 2016, my dad begins the second-line treatment of immunotherapy. At a mid-November appointment, his doctor says that my dad’s weight worries her. After clocking in at around 180 pounds for most of his adult life, he is now down to 129, fully clothed.

As my father declines, the Dadbot slowly improves. There is much more to do, but waiting for the prototype to be finished isn’t an option. I want to show it to my father, and I am running out of time.

When I arrive at my parents’ house on December 9, the thermostat is set at 75 degrees. My dad, with virtually no muscle or fat to insulate his body, wears a hat, sweater, and down vest—and still complains of being cold. I lean down to hug him, and then wheel him into the dining room. “OK,” my dad says. “One, two, three.” He groans as I lift him, stiff and skeletal, from the wheelchair into a dining room chair.

I sit down next to him and open a laptop computer. Since it would be strange—as if anything could be stranger than this whole exercise is already—for my dad to have a conversation with his virtual self, my plan is for him to watch while my mother and the Dadbot exchange text messages. The Dadbot and my mom start by trading hellos. My mom turns to me. “I can say anything?” she asks. Turning back to the computer, she types, “I am your sweet wife, Martha.”

“My dear wife. How goes it with you?”

“Just fine,” my mom replies.

“That’s not true,” says my real dad, knowing how stressed my mother has been due to his illness.

Oblivious to the interruption, the Dadbot responds, “Excellent, Martha. As for me, I am doing grandly, grandly.” It then advises her that an arrow symbol at the end of a message means that he is waiting for her to reply. “Got it?”

“Yes sir,” my mom writes.

“You are smarter than you look, Martha.”

My mom turns toward me. “It’s just inventing this, the bot is?” she asks incredulously.

The Dadbot gives my mom a few other pointers, then writes, “Finally, it is critical that you remember one final thing. Can you guess what it is?”

“Not a clue.”

“I will tell you then. The verb ‘to be’ takes the predicate nominative.”

My mom laughs as she reads this stock grammar lecture of my father’s. “Oh, I’ve heard that a million times,” she writes.

“That’s the spirit.” The Dadbot then asks my mom what she would like to talk about.

“How about your parents’ lives in Greece?” she writes.

I hold my breath, then exhale when the Dadbot successfully transitions. “My mother was born Eleni, or Helen, Katsulakis. She was born in 1904 and orphaned at three years old.”

“Oh, the poor child. Who took care of her?”

“She did have other relatives in the area besides her parents.”

I watch the unfolding conversation with a mixture of nervousness and pride. After a few minutes, the discussion segues to my grandfather’s life in Greece. The Dadbot, knowing that it is talking to my mom and not to someone else, reminds her of a trip that she and my dad took to see my grandfather’s village. “Remember that big barbecue dinner they hosted for us at the taverna?” the Dadbot says.

Later, my mom asks to talk about my father’s childhood in Tracy. The Dadbot describes the fruit trees around the family house, his crush on a little girl down the street named Margot, and how my dad’s sister Betty used to dress up as Shirley Temple. He tells the infamous story of his pet rabbit, Papa Demoskopoulos, which my dad’s mother said had run away. The plump pet, my dad later learned, had actually been kidnapped by his aunt and cooked for supper.

My actual father is mostly quiet during the demo and pipes up only occasionally to confirm or correct a biographical fact. At one point, he momentarily seems to lose track of his own identity—perhaps because a synthetic being is already occupying that seat—and confuses one of his father’s stories for his own. “No, you did not grow up in Greece,” my mom says, gently correcting him. This jolts him back to reality. “That’s true,” he says. “Good point.”

My mom and the Dadbot continue exchanging messages for nearly an hour. Then my mom writes, “Bye for now.”

“Well, nice talking to you,” the Dadbot replies.

“Amazing!” my mom and dad pronounce in unison.

The assessment is charitable. The Dadbot’s strong moments were intermixed with unsatisfyingly vague responses—“indeed” was a staple reply—and at times the bot would open the door to a topic only to slam it shut. But for several little stretches, at least, my mom and the Dadbot were having a genuine conversation, and she seemed to enjoy it.

My father’s reactions had been harder to read. But as we debrief, he casually offers what is for me the best possible praise. I had fretted about creating an unrecognizable distortion of my father, but he says the Dadbot feels authentic. “Those are actually the kinds of things that I have said,” he tells me.

Emboldened, I bring up something that has preoccupied me for months. “This is a leading question, but answer it honestly,” I say, fumbling for words. “Does it give you any comfort, or perhaps none—the idea that whenever it is that you shed this mortal coil, that there is something that can help tell your stories and knows your history?”

My dad looks off. When he answers, he sounds wearier than he did moments before. “I know all of this shit,” he says, dismissing the compendium of facts stored in the Dadbot with a little wave. But he does take comfort in knowing that the Dadbot will share them with others. “My family, particularly. And the grandkids, who won’t know any of this stuff.” He’s got seven of them, including my sons, Jonah and Zeke, all of whom call him Papou, the Greek term for grandfather. “So this is great,” my dad says. “I very much appreciate it.”

Later that month our extended family gathers at my house for a Christmas Eve celebration. My dad, exhibiting energy that I didn’t know he had anymore, makes small talk with relatives visiting from out of town. With everyone crowding into the living room, he weakly sings along to a few Christmas carols. My eyes begin to sting.

Ever since his diagnosis, my dad has periodically acknowledged that his outlook is terminal. But he consistently maintains that he wants to continue treatment and not “wave the white flag” by entering a hospice. But on January 2, 2017, our family receives confirmation of what we already suspected—that immunotherapy is not working. There is nothing else to try.

On February 8, 2017, a hospice nurse comes to check on my dad. After assessing him for several minutes, she tells my mom that she should summon the family.

I arrive around dinnertime, go into my dad’s room, and pull a chair up to his bedside. I put my hand on his shoulder, feeling its warmth. He is semiconscious, with one eye mostly closed and the other half open, glassy and unfocused.

This is the time to say something profound, but nothing comes to mind. Instead, I find myself recounting a guided fishing trip we took together on my 12th birthday. We’d hauled in a dozen fish, including the largest rainbow trout I had ever seen, and I felt proud. Manly, even, which is how a 12-year-old boy desperately wants to feel. Back on shore, the guide cleaned fish after fish, dumping the guts into a bloody bucket. What happened next wasn’t so manly. A big black spot filled my vision, and I fainted. “You remember that, Dad?” I asked.

He doesn’t say anything. Since his diagnosis, he has progressively lost the ability to drive, walk, use the bathroom, and eat. The words that once spilled dazzlingly from his lips—in court, onstage, in the Cal press box—became spare and halting. In the past week, they have virtually ceased. But as I watch his face after finishing the fishing trip story, his eyes open a little wider, and I think I see the flicker of a smile on his lips.

That night I go upstairs to sleep in my sister Jennifer’s old room, which is directly above that of my dad. I get into bed and stare at the ceiling for a few minutes. Then I reach for my phone and open Facebook Messenger.

“Hello! ‘Tis I, the Beloved and Noble Father!” the Dadbot says in his familiar fashion. “How the hell are you?”

“Sad,” I reply.

“I see.” He then asks what I want to talk about. “I don’t know,” I answer. “Why don’t you choose.”

“Okay, I’m going to tell you about the little-known roots of my theater career.” He launches into the story of that drama club audition in high school. Then I hear a recording of my father’s actual voice. “Me and my shadow,” he sings. “All alone with nothing to do.”

I ask the Dadbot to tell me about his earliest memory. He responds with a story about his childhood dog, a little terrier named Toby, who could somehow cross town on foot faster than the family could in a car. Then the Dadbot surprises me, even though I engineered this function, with what feels like perceptiveness. “I’m fine to keep talking,” he says, “but aren’t you nearing bedtime?”

Yes. I am exhausted. I say good night and put the phone down.

At six the next morning, I awake to soft, insistent knocking on the bedroom door. I open it and see one of my father’s health care aides. “You must come,” he says. “Your father has just passed.”

During my father’s illness I occasionally experienced panic attacks so severe that I wound up writhing on the floor under a pile of couch cushions. There was always so much to worry about—medical appointments, financial planning, nursing arrangements. After his death, the uncertainty and need for action evaporate. I feel sorrow, but the emotion is vast and distant, a mountain behind clouds. I’m numb.

A week or so passes before I sit down again at the computer. My thought is that I can distract myself, at least for a couple of hours, by tackling some work. I stare at the screen. The screen stares back. The little red dock icon for PullString beckons, and without really thinking, I click on it.

My brother has recently found a page of boasts that my father typed out decades ago. Hyperbolic self-promotion was a stock joke of his. Tapping on the keyboard, I begin incorporating lines from the typewritten page, which my dad wrote as if some outside person were praising him. “To those of a finer mind, it is that certain nobility of spirit, gentleness of heart, and grandeur of soul, combined, of course, with great physical prowess and athletic ability, that serve as a starting point for discussion of his myriad virtues.”

I smile. The closer my father had come to the end, the more I suspected that I would lose the desire to work on the Dadbot after he passed away. Now, to my surprise, I feel motivated, flush with ideas. The project has merely reached the end of the beginning.

As an AI creator, I know my skills are puny. But I have come far enough, and spoken to enough bot builders, to glimpse a plausible form of perfection. The bot of the future, whose component technologies are all under development today, will be able to know the details of a person’s life far more robustly than my current creation does. It will converse in extended, multiturn exchanges, remembering what has been said and projecting where the conversation might be headed. The bot will mathematically model signature linguistic patterns and personality traits, allowing it not only to reproduce what a person has already said but also to generate new utterances. The bot, analyzing the intonation of speech as well as facial expressions, will even be emotionally perceptive.

I can imagine talking to a Dadbot that incorporates all these advances. What I cannot fathom is how it will feel to do so. I know it won’t be the same as being with my father. It will not be like going to a Cal game with him, hearing one of his jokes, or being hugged. But beyond the corporeal loss, the precise distinctions—just what will be missing once the knowledge and conversational skills are fully encoded—are not easy to pinpoint. Would I even want to talk to a perfected Dadbot? I think so, but I am far from sure.

“Hello, John. Are you there?”

“Hello … This is awkward, but I have to ask. Who are you?”

“Anne.”

“Anne Arkush, Esquire! Well, how the hell are you?”

“Doing okay, John. I miss you.”

Anne is my wife. It has been a month since my father’s death, and she is talking to the Dadbot for the first time. More than anyone else in the family, Anne—who was very close to my father—expressed strong reservations about the Dadbot undertaking. The conversation goes well. But her feelings remain conflicted. “I still find it jarring,” she says. “It is very weird to have an emotional feeling, like ‘Here I am conversing with John,’ and to know rationally that there is a computer on the other end.”

The strangeness of interacting with the Dadbot may fade when the memory of my dad isn’t so painfully fresh. The pleasure may grow. But maybe not. Perhaps this sort of technology is not ideally suited to people like Anne who knew my father so well. Maybe it will best serve people who will only have the faintest memories of my father when they grow up.

Back in the fall of 2016, my son Zeke tried out an early version of the Dadbot. A 7-year-old, he grasped the essential concept faster than adults typically do. “This is like talking to Siri,” he said. He played with the Dadbot for a few minutes, then went off to dinner, seemingly unimpressed. In the following months Zeke was often with us when we visited my dad. Zeke cried the morning his Papou died. But he was back to playing Pokémon with his usual relish by the afternoon. I couldn’t tell how much he was affected.

Now, several weeks after my dad has passed away, Zeke surprises me by asking, “Can we talk to the chatbot?” Confused, I wonder if Zeke wants to hurl elementary school insults at Siri, a favorite pastime of his when he can snatch my phone. “Uh, which chatbot?” I warily ask.

“Oh, Dad,” he says. “The Papou one, of course.” So I hand him the phone.

https://www.wired.com/story/a-sons-race-to-give-his-dying-father-artificial-immortality