by Antonio Regalado

The startup accelerator Y Combinator is known for supporting audacious companies in its popular three-month boot camp.

There’s never been anything quite like Nectome, though.

Next week, at YC’s “demo days,” Nectome’s cofounder, Robert McIntyre, is going to describe his technology for exquisitely preserving brains in microscopic detail using a high-tech embalming process. Then the MIT graduate will make his business pitch. As it says on his website: “What if we told you we could back up your mind?”

So yeah. Nectome is a preserve-your-brain-and-upload-it company. Its chemical solution can keep a body intact for hundreds of years, maybe thousands, as a statue of frozen glass. The idea is that someday in the future scientists will scan your bricked brain and turn it into a computer simulation. That way, someone a lot like you, though not exactly you, will smell the flowers again in a data server somewhere.

This story has a grisly twist, though. For Nectome’s procedure to work, it’s essential that the brain be fresh. The company says its plan is to connect people with terminal illnesses to a heart-lung machine in order to pump its mix of scientific embalming chemicals into the big carotid arteries in their necks while they are still alive (though under general anesthesia).

The company has consulted with lawyers familiar with California’s two-year-old End of Life Option Act, which permits doctor-assisted suicide for terminal patients, and believes its service will be legal. The product is “100 percent fatal,” says McIntyre. “That is why we are uniquely situated among the Y Combinator companies.”

There’s a waiting list

Brain uploading will be familiar to readers of Ray Kurzweil’s books or other futurist literature. You may already be convinced that immortality as a computer program is definitely going to be a thing. Or you may think transhumanism, the umbrella term for such ideas, is just high-tech religion preying on people’s fear of death.

Either way, you should pay attention to Nectome. The company has won a large federal grant and is collaborating with Edward Boyden, a top neuroscientist at MIT, and its technique just claimed an $80,000 science prize for preserving a pig’s brain so well that every synapse inside it could be seen with an electron microscope.

McIntyre, a computer scientist, and his cofounder Michael McCanna have been following the tech entrepreneur’s handbook with ghoulish alacrity. “The user experience will be identical to physician-assisted suicide,” he says. “Product-market fit is people believing that it works.”

Nectome’s storage service is not yet for sale and may not be for several years. Also still lacking is evidence that memories can be found in dead tissue. But the company has found a way to test the market. Following the example of electric-vehicle maker Tesla, it is sizing up demand by inviting prospective customers to join a waiting list for a deposit of $10,000, fully refundable if you change your mind.

So far, 25 people have done so. One of them is Sam Altman, a 32-year-old investor who is one of the creators of the Y Combinator program. Altman tells MIT Technology Review he’s pretty sure minds will be digitized in his lifetime. “I assume my brain will be uploaded to the cloud,” he says.

Old idea, new approach

The brain storage business is not new. In Arizona, the Alcor Life Extension Foundation holds more than 150 bodies and heads in liquid nitrogen, including those of baseball great Ted Williams. But there’s dispute over whether such cryonic techniques damage the brain, perhaps beyond repair.

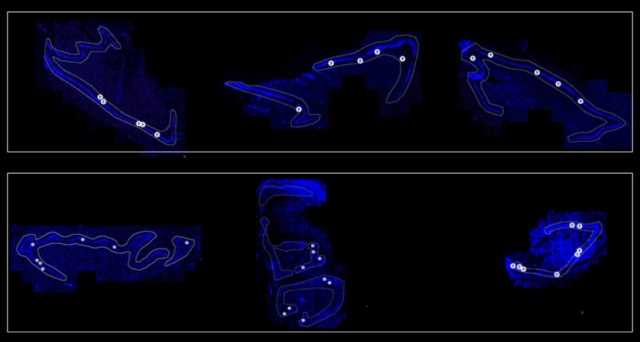

So starting several years ago, McIntyre, then working with cryobiologist Greg Fahy at a company named 21st Century Medicine, developed a different method, which combines embalming with cryonics. It proved effective at preserving an entire brain to the nanometer level, including the connectome—the web of synapses that connect neurons.

A connectome map could be the basis for re-creating a particular person’s consciousness, believes Ken Hayworth, a neuroscientist who is president of the Brain Preservation Foundation—the organization that, on March 13, recognized McIntyre and Fahy’s work with the prize for preserving the pig brain.

There’s no expectation here that the preserved tissue can be actually brought back to life, as is the hope with Alcor-style cryonics. Instead, the idea is to retrieve information that’s present in the brain’s anatomical layout and molecular details.

“If the brain is dead, it’s like your computer is off, but that doesn’t mean the information isn’t there,” says Hayworth.

A brain connectome is inconceivably complex; a single nerve can connect to 8,000 others, and the brain contains millions of cells. Today, imaging the connections in even a square millimeter of mouse brain is an overwhelming task. “But it may be possible in 100 years,” says Hayworth. “Speaking personally, if I were a facing a terminal illness I would likely choose euthanasia by [this method].”

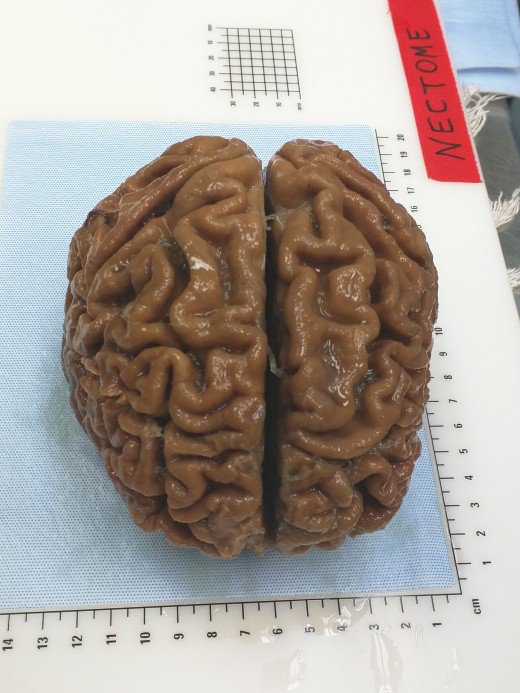

A human brain

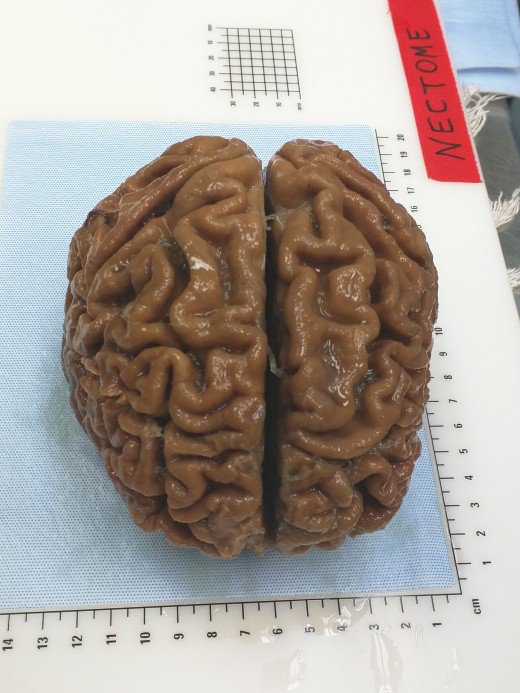

The Nectome team demonstrated the seriousness of its intentions starting this January, when McIntyre, McCanna, and a pathologist they’d hired spent several weeks camped out at an Airbnb in Portland, Oregon, waiting to purchase a freshly deceased body.

In February, they obtained the corpse of an elderly woman and were able to begin preserving her brain just 2.5 hours after her death. It was the first demonstration of their technique, called aldehyde-stabilized cryopreservation, on a human brain.

Fineas Lupeiu, founder of Aeternitas, a company that arranges for people to donate their bodies to science, confirmed that he provided Nectome with the body. He did not disclose the woman’s age or cause of death, or say how much he charged.

The preservation procedure, which takes about six hours, was carried out at a mortuary. “You can think of what we do as a fancy form of embalming that preserves not just the outer details but the inner details,” says McIntyre. He says the woman’s brain is “one of the best-preserved ever,” although her being dead for even a couple of hours damaged it. Her brain is not being stored indefinitely but is being sliced into paper-thin sheets and imaged with an electron microscope.

McIntyre says the undertaking was a trial run for what the company’s preservation service could look like. He says they are seeking to try it in the near future on a person planning doctor-assisted suicide because of a terminal illness.

Hayworth told me he’s quite anxious that Nectome refrain from offering its service commercially before the planned protocol is published in a medical journal. That’s so “the medical and ethics community can have a complete round of discussion.”

“If you are like me, and think that mind uploading is going to happen, it’s not that controversial,” he says. “But it could look like you are enticing someone to commit suicide to preserve their brain.” He thinks McIntyre is walking “a very fine line” by asking people to pay to join a waiting list. Indeed, he “may have already crossed it.”

Crazy or not ?

Some scientists say brain storage and reanimation is an essentially fraudulent proposition. Writing in our pages in 2015, the McGill University neuroscientist Michael Hendricks decried the “abjectly false hope” peddled by transhumanists promising resurrection in ways that technology can probably never deliver.

“Burdening future generations with our brain banks is just comically arrogant. Aren’t we leaving them with enough problems?” Hendricks told me this week after reviewing Nectome’s website. “I hope future people are appalled that in the 21st century, the richest and most comfortable people in history spent their money and resources trying to live forever on the backs of their descendants. I mean, it’s a joke, right? They are cartoon bad guys.”

Nectome has received substantial support for its technology, however. It has raised $1 million in funding so far, including the $120,000 that Y Combinator provides to all the companies it accepts. It has also won a $960,000 federal grant from the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health for “whole-brain nanoscale preservation and imaging,” the text of which foresees a “commercial opportunity in offering brain preservation” for purposes including drug research.

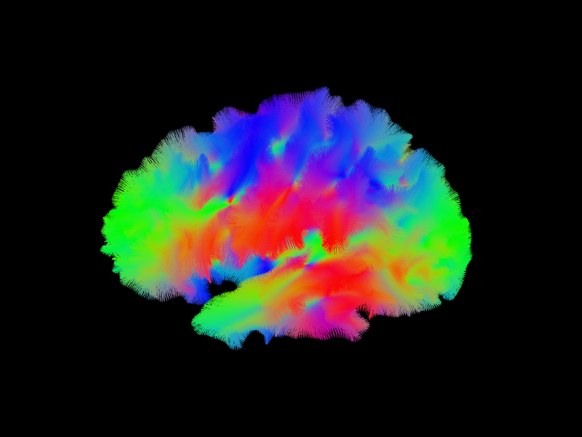

About a third of the grant funds are being spent in the MIT laboratory of Edward Boyden, a well-known neuroscientist. Boyden says he’s seeking to combine McIntyre’s preservation procedure with a technique MIT invented, expansion microscopy, which causes brain tissue to swell to 10 or 20 times its normal size, and which facilitates some types of measurements.

I asked Boyden what he thinks of brain preservation as a service. “I think that as long as they are up-front about what we do know and what we don’t know, the preservation of information in the brain might be a very useful thing,” he replied in an e-mail.

The unknowns, of course, are substantial. Not only does no one know what consciousness is (so it will be hard to tell if an eventual simulation has any), but it’s also unclear what brain structures and molecular details need to be retained to preserve a memory or a personality. Is it just the synapses, or is it every fleeting molecule? “Ultimately, to answer this question, data is needed,” Boyden says.

Demo day

Nectome has been honing its pitch for Y Combinator’s demo days, trying to create a sharp two-minute summary of its ideas to present to a group of elite investors. The team was leaning against showing an image of the elderly woman’s brain. Some people thought it was unpleasant. The company had also walked back its corporate slogan, changing it from “We archive your mind” to “Committed to the goal of archiving your mind,” which seemed less like an overpromise.

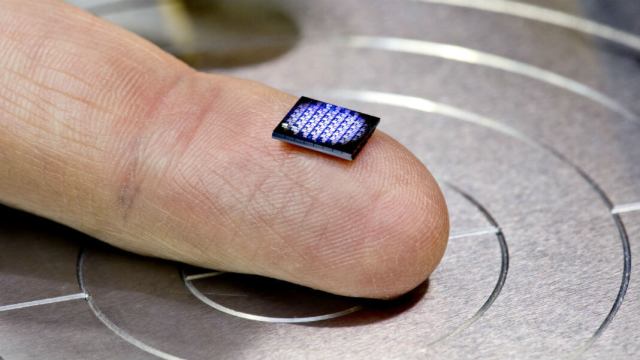

McIntyre sees his company in the tradition of “hard science” startups working on tough problems like quantum computing. “Those companies also can’t sell anything now, but there is a lot of interest in technologies that could be revolutionary if they are made to work,” he says. “I do think that brain preservation has amazing commercial potential.”

He also keeps in mind the dictum that entrepreneurs should develop products they want to use themselves. He sees good reasons to save a copy of himself somewhere, and copies of other people, too.

“There is a lot of philosophical debate, but to me a simulation is close enough that it’s worth something,” McIntyre told me. “And there is a much larger humanitarian aspect to the whole thing. Right now, when a generation of people die, we lose all their collective wisdom. You can transmit knowledge to the next generation, but it’s harder to transmit wisdom, which is learned. Your children have to learn from the same mistakes.”

“That was fine for a while, but we get more powerful every generation. The sheer immense potential of what we can do increases, but the wisdom does not.”

https://www.technologyreview.com/s/610456/a-startup-is-pitching-a-mind-uploading-service-that-is-100-percent-fatal/